Adapting Glassmaking Knowledge and Labour Structures in Early Modern Britain

This blog is based upon the research funded by a grant awarded by the Economic History Society through its Research Fund for Graduate Students to Oliver Gunning of Northumbria University. The research forms part of the author’s PhD thesis, entitled: “Migration, Innovation, and Glassmaking in Early Modern Britain”.

—

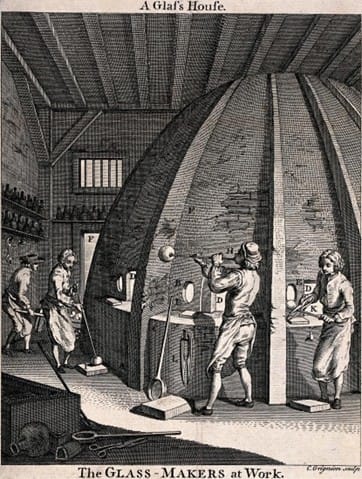

The migration of skilled workers was crucial in the growth of the early modern economy, which paved the way for the industrial revolution in Britain. Notably, the mobility of workers connected with coal-based industries, such as iron, glass, and ceramics, allowed for the exchange of ideas and advancements in techniques critical to the Industrial Revolution. As artisan workers travelled from region to region and shared their craft knowledge, new products and methods were created, resulting from skilled adaptation. This blog post will examine how glassmakers changed their labour and knowledge structures when migrating to the British Isles to facilitate the manufacture of new products.

From the 1560s onwards, the British Isles imported its glassmaking knowledge from European centres of glass manufacturing, such as Venice, Lorraine, and Normandy, to reduce the consumption of imported goods. Glassmakers Thomas and Balthazaar de Hennezell migrated to England from Lorraine in 1568 and were contracted to transfer their skills in window-making to the local populations. However, they refused to share their skills through apprenticeship systems, choosing to practice, but not pass on, their skills. Parallel situations appeared in another glass manufactory in 1576. Italian migrant Jacopo Verzellini refused to teach apprentices his Venetian crystal glass-making skills but continued producing the product.

Consequently, a structure of production developed in England and Scotland, whereby glass manufactories relied upon individual skilled workers to make desirable goods in the British Isles, which remained in place throughout the seventeenth and the eighteenth century. Skilled immigrants and their descendants adapted glassmaking techniques to fit the specific conditions of England and Scotland, managing to make advancements while also keeping their trade secrets closely guarded. Individuals related to the Hennezell family were discovered working in glassworks in Leith during 1621, 1692, and 1698, Newcastle-upon-Tyne during 1619, 1679, and 1739, and Glasgow during 1776. On each occasion, these workers were hired to introduce a new product line or rescue a struggling business.

Adapting a style of knowledge circulation developed during the sixteenth century in Piedmont, Venice, and Lorraine, the glassworkers established an informal, proprietary knowledge system centring the important micro-innovations of the craft in their family networks. No formal institution was established, and most immigrant glassmakers did not enrol in guilds, unlike glaziers, who cut and finished glass within guild jurisdictions. They maintained a cultural code of exclusivity, refusing to transfer their skills to the local populations. This structure substituted formal guild structures and encouraged innovation or provided communal exchange that the guild provided for other crafts. This isolated glassmakers in glassmaking communities, which were often mistaken for enclaves of religious dissidence, as the glassmakers looked to maintain their outsider identity by grouping with other outsiders such as Quakers in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Catholics in Leith. Outsiders were included in Newcastle-upon-Tyne when glassmakers lacked capital investment. Still, in these agreements, the furnace and workshop remained strictly in control of the immigrant communities, with the outsider gaining shares of the profits.

Occasionally, innovations were patented by merchants or entrepreneurs. For example, in 1674, a new method of making crystal glass was patented by George Ravenscroft, an English merchant who utilised new techniques to use lead to produce clear glass. However, the process was created by glassworkers John Odaccio Formica, John Baptista da Costa, and Jean Guillaume Renier, whom Ravenscroft imported from Nijmegen. Importing migrants with new skills was attempted at Leith in 1698 in the cases of Moses Henzell, Onisiphorous Dagnia, and Daniel Tyterry. To establish furnaces and acquire resources, it was necessary to have sufficient capital, which merchants provided. The importance of immigrant glass workers was acknowledged, as patents were obtained to secure the exclusivity of the produced goods rather than the exclusivity of the technique, as similar techniques were seen in non-patented glass works simultaneously, such as Leith.

Following the emergence of the Great Divergence debate, economic historians and historians of science and technology have identified Britain’s unique economic development as centring upon its different property rights, institutions, and empire and its differing attitude to new technologies. As a case study, early modern glassmaking in the British Isles shows significant continuations between European glassmaking knowledge and labour structures that adapted to fit differing locales. Craft workers could change their economic role and skills across different borders. This occurred outside of institutions such as guilds and patents. The workers’ knowledge, acquired through their migration across Europe and the British Isles, allowed them to adjust recipes and techniques to different conditions.

To contact the author:

Oliver Gunning

oliver.gunning@northumbria.ac.uk

Northumbria University

References:

Berg, Maxine, and Pat Hudson. Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution. Polity, 2023.

Bertucci, Paola. Artisanal Enlightenment : Science and the Mechanical Arts in Old Regime France. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2017.

Dupré, Sven. “The Nature of Glass: Technologies of Transparency, Materials on the Move.” Isis 114, no. 2 (2023): 393-99. https://doi.org/10.1086/724806. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/724806.

Maitte, Corine. “Artisan Mobility and the Circulaton of Knowledge in the Glass Industry in Early Modern Europe.” In The Republic of Skill: Artisan Mobility, Innovation, and the Circulation of Knowledge in Premodern Europe, edited by David Garrioch, 65-89. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2022.

Mokyr, Joel. “Bottom-up or Top-Down? The Origins of the Industrial Revolution.” Journal of Institutional Economics 14, no. 6 (2018): 1003-24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174413741700042X.

Trivellato, Francesca. “Murano Glass, Continuity and Transformation (1400-1800).” In At the Center of the Old World: Trade and Manufacturing in Venice and the Venetian Mainland, 1400-1800, edited by Paola Lanaro, 143-83. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2006.