British perceptions of German post-war industrial relations

By Colin Chamberlain (University of Cambridge)

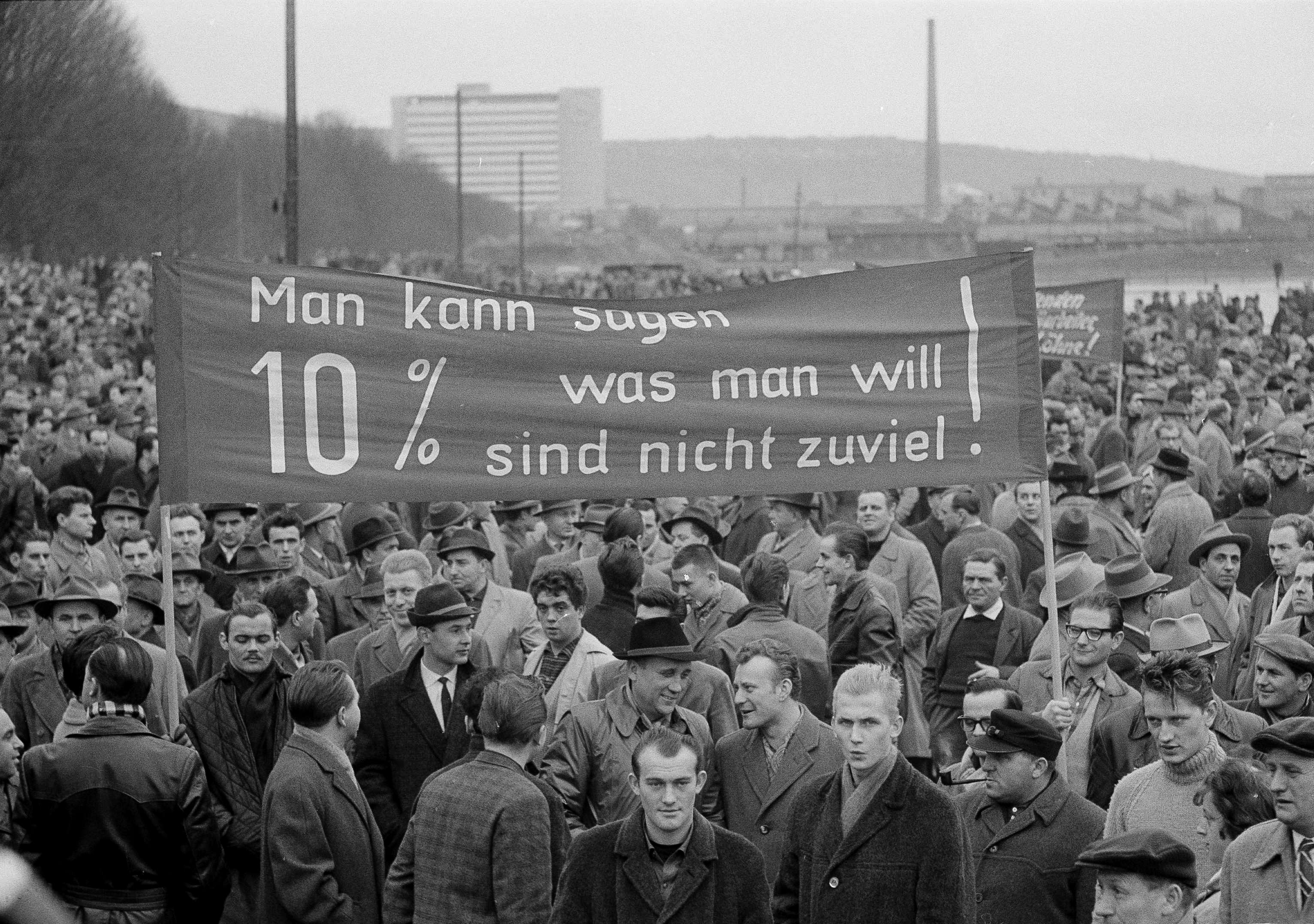

‘Almost idyllic’ – this was the view of one British commentator on the state of post-war industrial relations in West Germany. No one could say the same about British industrial relations. Here, industrial conflict grew inexorably from year to year, forcing governments to expend ever more effort on preserving industrial peace.

Deeply frustrated, successive governments alternated between appeasing trade unionists and threatening them with new legal sanctions in an effort to improve their behaviour, thereby avoiding tackling the fundamental issue of their institutional structure. If the British had only studied the German ‘model’ of industrial relations more closely, they would have understood better the reforms that needed to be made.

Britain’s poor state of industrial relations was a major, if not the major, factor holding back Britain’s economic growth, which was regularly less than half the rate in Germany, not to speak of the chronic inflation and balance of payments problems that only made matters worse. So, how come the British did not take a deeper look at the successful model of German industrial relations and learn any lessons?

Ironically, the British were in control of Germany at the time the trade union movement was re-establishing itself after the war. The Trades Union Congress and the British labour movement offered much goodwill and help to the Germans in their task.

But German trade unionists had very different ideas to the British trade unions on how to go about organising their industrial relations, ideas that the British were to ignore consistently over the post-war period. These included:

-

- In Britain, there were hundreds of trade unions, but in Germany, there were only 16 re-established after the war, each representing one or more industries, thereby avoiding the demarcation disputes so common in Britain.

- Terms and conditions were negotiated on this industry-basis by strong well-funded trade unions, which welcomed the fact that their two or three year long collective agreements were legally enforceable in Germany’s system of industrial courts.

- Trade unions were not involved in workplace grievances and disputes. These were left to employees and managers meeting together in Germany’s highly successful works councils to resolve such issues informally along with engaging in consultative exercises on working practices and company reorganisations. As a result, German companies did not seek to lay-off staff as British companies did on any fall in demand, but rathet to retrain and reallocate them.

British trade unions pleaded that their very untidy institutional structure with hundreds of competing trade unions was what their members actually wanted and should therefore be outside any government interference. The trade unions jealously guarded their privileges and especially rejected any idea of industry-based unions, legally enforceable collective agreements and works councils.

A heavyweight Royal Commission was appointed, but after three years’ deliberation, it came up with little more than the status quo. It was reluctant to study any ideas emanating from Germany.

While the success of industrial relations in Germany was widely recognised in Britain, there was little understanding about why this was so or indeed much interest in it. The British were deeply conservative about the ‘institutional shape’ of industrial relations and had a fear of putting forward any radical German ideas. Britain was therefore at a big disadvantage as far as creating modern trade unions operating in a modern state.

So, what economic price the failure to sort out the institutional structure of the British trade unions?