Community, Educational Reform and Migration in Late Imperial China

In this blog post, Christoph Hess, who studied for his PhD at the University of Cambridge, introduces his research, which was assisted by the Research Fund for Graduate Students of the Economic History Society.

—

It was late November 2016, and I was sitting in a small, unheated classroom full of books at my Chinese university, ready for the lecture to finish and discussion to start. Our professor spoke with a clear northern accent from Shandong Province that was easy to follow, and was always in a light mood, which is why I had decided to bring along a friend this time. When she raised her voice to ask a question, our professor immediately recognised her accent. “Are you from Shandong too?” he asked. She explained that she was in fact from Liaoning Province, further north, but that all her ancestors had moved there from Shandong. Not just her family, but about two-thirds of people in their hometown traced their ancestry to Shandong Province.

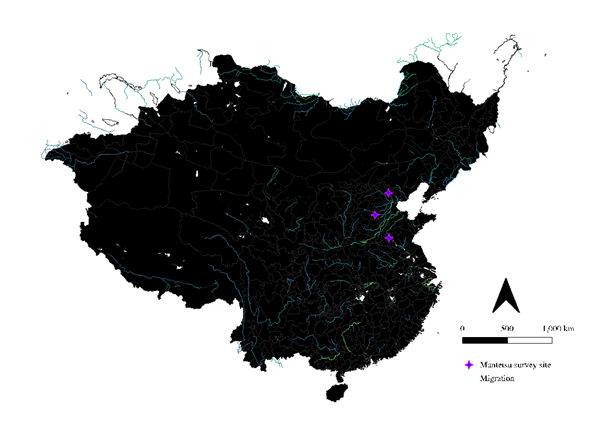

Like my friend, many people in China are the children of migrants who had left their home in the late imperial (here ca. 1650-1911) or Republican (1912-1949) era. But we know little about what distinguished these migrants from their non-migrant peers. The aim of this project is to build the first individual-level dataset of migration in China’s economic heartland, the Lower Yangzi region, by using geographic information from lineage genealogies. I started by sifting through the individual biographies of people recorded in these genealogies before I developed methods to automate the transcription process and raise the size of my sample from a few thousand to ca. 26,000 observations. With the help of the Economic History Society’s Research Fund for Graduate Students, I could hire research assistants to help me with cleaning the data and linking fathers to sons in the dataset. The migration trajectories based on the georeferenced dataset, as well as the sites of three Japanese surveys I used for qualitative information, are shown in Map 1.

Source: Lower Yangzi Genealogy Dataset. Base map from China Historical GIS © Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Fudan University

By comparing the share of men who had passed the various levels of the imperial state examinations in my sample with available data on regional averages, I could show that my dataset is likely to be representative of local populations.

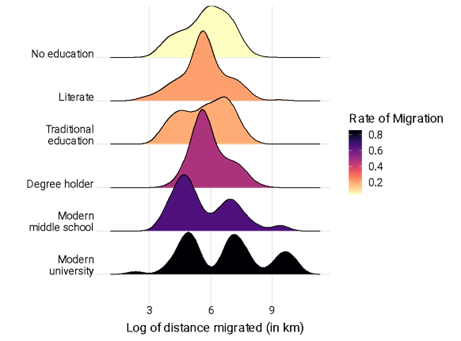

Education soon turned out to be one of the most crucial factors influencing migration. I assigned educational scores based on information in the genealogies, such as whether they were degree holders who had passed the state examinations, or if they had a pen name, showing that they were literate.

But as Figure 1 shows, although men experienced higher geographic mobility at all levels of education, not all forms of education increased either the likelihood of migrating, or the distance migrated to the same extent. Men who had been groomed in the Confucian tradition (‘traditional education’) were much less mobile than those who had either attended a Western-style middle school or university. Adding controls in a statistical model of distance migrated and a discontinuity analysis focusing on the historical break of abolishing the state examinations in 1905 do not alter this core finding.

Source: Lower Yangzi Genealogy Dataset.

While Confucian education equipped young men with a fluency in literature, poetry, dynastic histories, and gave them access to an official career, institutions modelled after Western examples provided a more skills-oriented and often overtly occupational training. These skills opened the doors to a pool of economic opportunities inside and outside China. While we know that wage differentials and employment opportunities shaped flows of migration in both historical and contemporary economies, this presupposes the existence of a single labour market between these different opportunities. A skills-based educational system was important for this single labour market insofar as the market required a standardisation of educational profiles. Although changes in economic and social structure could give rise to opportunities for migrants, a complementary educational regime was needed to create a workforce ready to take up these opportunities. However, despite the great success of educational programmes, the historical disruptions of the mid-twentieth century, soon followed by a system of household registration that reinstated legal ties to the land, meant that the trend towards widespread migration of skilled labour was not realised until the late twentieth century.

To contact the author:

Christoph Hess

christoph.hess1@gmail.com

University of Cambridge