Competition and rent-seeking during the slave trade

by Jose Corpuz (University of Warwick)

The Royal African Company of England (RAC) gave gifts and similar payments to African chiefs for exclusive services. But African chiefs who could stop or redirect trade from inland could extract payments from RAC, particularly when competition from other English merchants increased.

There is a lot of descriptive evidence on rent-seeking in Africa during the slave trade. My research provides quantitative evidence of rent-seeking and shows that it changed over time. I constructed the database of more than 20,000 payments myself, from handwritten seventeenth century RAC archives.

My study contributes to the debate about rent-seeking during the slave trade. The ‘fishers-of-men’ view argues that slaves were a common property resource and competition among enslavers would dissipate any rents (Thomas and Bean, 1974). The ‘hunters-of-rent’ view, however, argues that the competition was restricted by barriers to entry, enabling rents (Evans and Richardson, 1995).

My research provides quantitative evidence that rent-seeking existed and shows when, where and how much rent-seeking increased during the slave trade.

I used my own dataset to examine rent-seeking during the slave trade, looking at more than 20,000 payments (for example ‘dashey,’ a local term used in West Africa which literally means gift) that the RAC made to seventeenth century chiefs in Ghana. RAC made these payments to African chiefs in return for exclusive trade with caravan merchants from inland. These payments were separate from any price paid for slaves themselves.

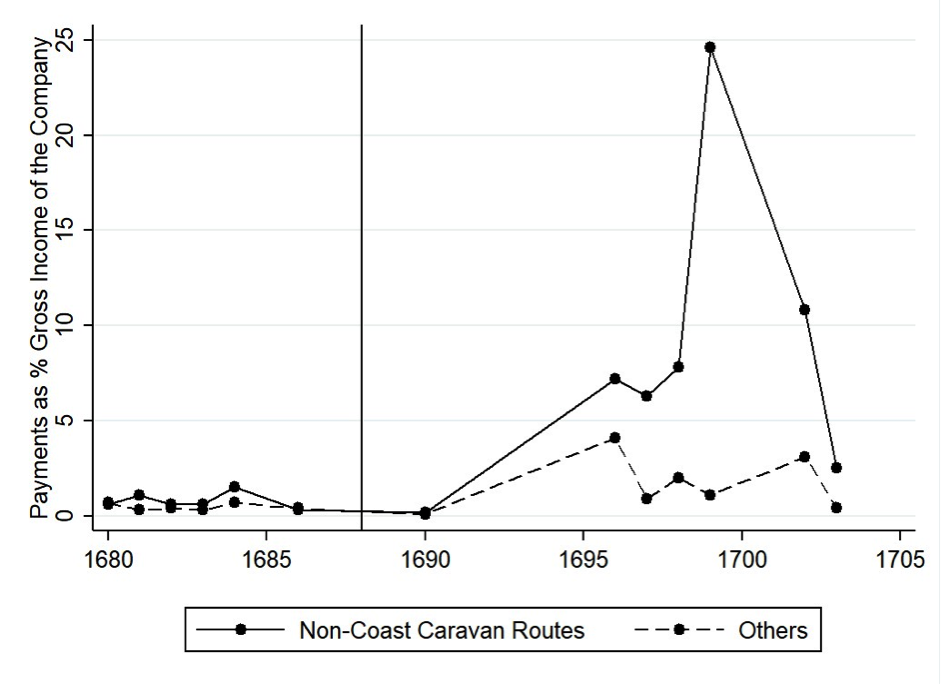

I use an event study to show that this power of chiefs increased when the RAC lost royal privileges after the Glorious Revolution in 1688, and this change increased competition from other English merchants.

I answer three questions. First: what was the distribution of payments across chiefs?

I find that the distribution of payments to chiefs was unequal. In particular, the highest-ranking head chiefs received the greatest value of payments per capita. These findings provide quantitative evidence that the slave trade was ‘the business of kings, rich men, and prime merchants’ (in other words, elites) and that the distribution of payments among them was unequal (Hopkins, 1973).

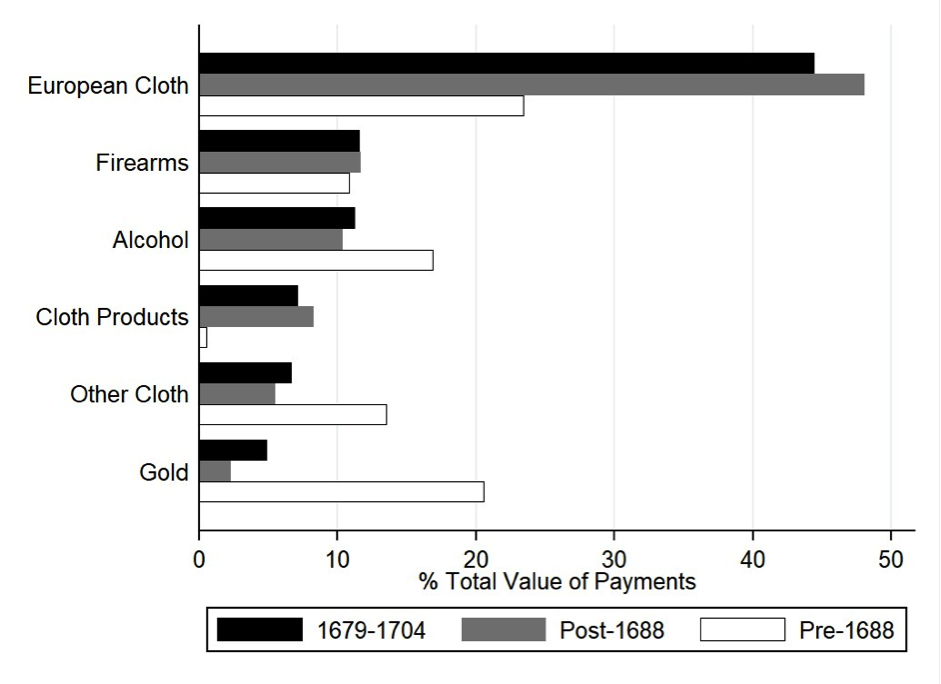

Second: what commodities were included and how did this change over time?

Usually, the payments were European cloth, firearms and alcohol. Head chiefs used European cloth to signal authority and prestige, and received most of the European cloth, particularly when their bargaining position improved after 1688.

These findings highlight the importance of payments as a channel through which European merchants supplied goods in response to African demand. Unlike Rodney’s (1988) ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’ thesis, European merchants did not determine the goods they supplied to Africans, and Africans were not passive recipients of these goods.

Third: did payments rise after the Glorious Revolution in 1688, reducing the RAC’s privileges – such as the power to seize other English merchants’ ships and cargoes (Davies, 1957; Carlos and Kruse, 1996) – and facilitating competition from other English merchants?

Using ‘diff-in-diff’ estimation, I find that the RAC made greater payments to chiefs whose compliance was most important in deterring other English merchants from competing with the RAC after 1688.

In particular, I find that payments increased the most to chiefs in ‘non-coast caravan routes’ or locations where they could stop or redirect trade flowing from inland. The chiefs demanded an increased share of the RAC’s total revenue. Qualitative evidence from the letters (Law, 2001, 2006, 2010) supports the view that this increase can be explained by the chiefs’ increased bargaining power.

Overall, the findings are consistent with the hunters-of-rent view of rent-seeking during the slave trade. Some chiefs found themselves in the right place at the right time and took advantage of the situation.

Overall, the findings are consistent with the hunters-of-rent view of rent-seeking during the slave trade. Some chiefs found themselves in the right place at the right time and took advantage of the situation.

References

Carlos, AM, and J Brown-Kruse (1996) ‘The decline of the Royal African Company: Fringe firms and the role of the charter’, Economic History Review 49(2): 291-313.

Davies, KG (1957) The Royal African Company, Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd.

Evans, EW, and D Richardson (1995) ‘Hunting for rents: The economics of slaving in pre-colonial Africa’, Economic History Review 48(4): 665-86.

Hopkins, AG (1973) An Economic History of West Africa, Routledge.

Law, R (2001, 2006, 2010) The English in West Africa, 1685-1698: The local correspondence of the Royal African Company of England, 1681-1699 (Vols. 1-3), Oxford University Press.

Rodney, W (1988) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Bogle-L’Ouverhure Publications.

Thomas, RP, and RN Bean (1974) ‘The fishers of men: The profits of the slave trade’, Journal of Economic History 34(4): 885-914.