Deindustrialisation in ‘troubled’ Belfast: evidence of the links between factory closures and sectarianism – and lessons from the community response

by Christopher Lawson (University of California, Berkeley)

This paper was presented at the EHS Annual Conference 2019 in Belfast.

My new research provides fresh insights into the relationship between industrial decline and sectarian conflict in late twentieth century Belfast, and increases our understanding of how communities respond to the loss of their economic base.

The poverty and deprivation that continues to afflict much of West Belfast is usually understood as a direct result of the sectarian ‘Troubles’ of the 1960s to 1990s, when ‘ancient’ ethnic and religious hatreds erupted and brought economic misery as investment fled.

But industrial decline actually predated the ‘Troubles’, and was a cause rather than an effect of sectarian tension. The linen industry, on which West Belfast had been built, shed tens of thousands of jobs in the 20 years following the Second World War, leading to some of the highest unemployment rates in the entire UK by the mid-1960s.

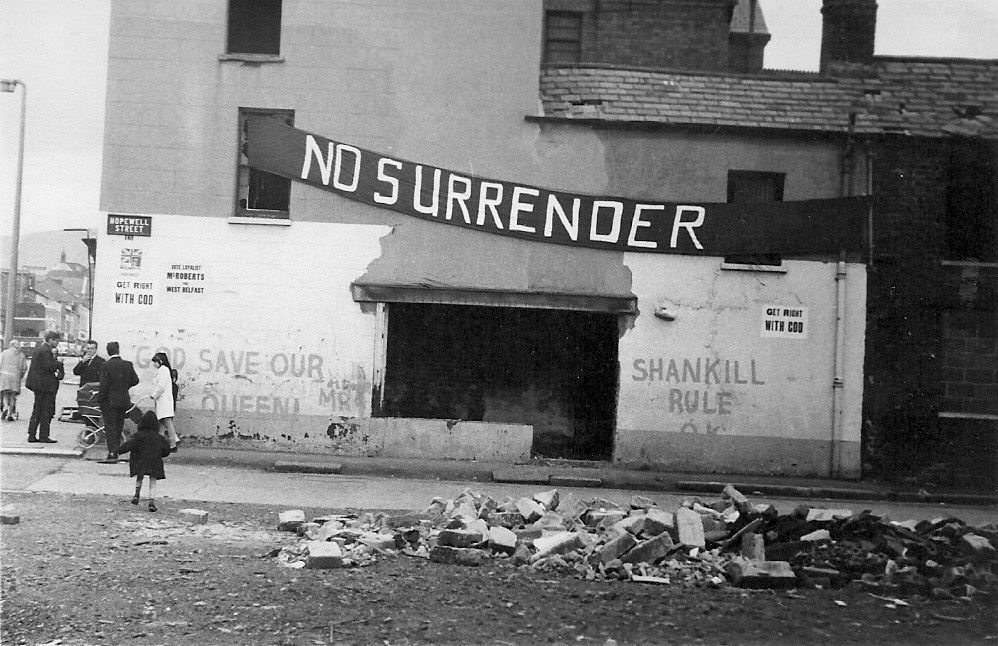

I argue that it was the social consequences of the collapse of the linen industry that made West Belfast neighbourhoods like the Shankill and the Falls such centres of conflict in the following decades. West Belfast communities were caught in a downward spiral, where unemployment and urban decay was exploited by those seeking to promote sectarian resentment, leading to violence, which in turn made the economic conditions even worse.

In addition to showing how deindustrialisation helped spur the ‘Troubles’ in West Belfast, my research also shows how new community organisations sprang up to fill the gap left by government and lead the effort to adapt to post-industrial world.

I focus particularly on the creation of the Shankill Community Council and Ardoyne People’s Assembly, on either side of the sectarian divide in West Belfast. These organisations are usually seen as outgrowths of the Troubles, focused on defending their communities from sectarian violence, but my research shows that their primary focus was actually on re-development and reversing economic decline.

These organisations recognised that the linen industry would not be returning, and instead focused on education, daycare, skills retraining and transport linkages. In communities where more than 70% of adolescents left school without any qualifications whatsoever, improved education was essential if young people were to build meaningful lives and resist the temptation to join sectarian paramilitaries.

The emphasis on quality daycare was part of a larger effort to reduce the barriers preventing women from entering the workforce as equals to men, as community leaders recognised that the idea of the ‘male breadwinner’ was a thing of the past.

Although the progress of these organisations was slow, their efforts helped to begin the process of economic and social recovery, and they set the agenda for government support in the post-Good Friday Agreement era. The Shankill Women’s Centre, an outgrowth of the Shankill Community Council, would receive significant government support from New Labour and from the new Northern Ireland Assembly, and it continues to provide subsidised daycare in the neighbourhood.

With deindustrialisation widely recognised as a contributing factor in the UK’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union and the election of Donald Trump, it is important that we understand the serious social and cultural consequences that such dramatic economic dislocation can have.

My research helps to provide a better understanding of the role of deindustrialisation in the outbreak of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, but also shows how bottom-up social action can make a genuine difference in the process of recovery. In this way, it provides lessons that can be applied to struggling post-industrial communities across the Western world.