Did early modern Europeans fail to look after their poor? Poverty and poor relief in France and Spain, c. 1600-1800.

This blog post is based on a grant awarded to Professor Julie Marfany of the University of Durham by the Economic History Society through the Carnevali Small Research Grants scheme.

—

In her now classic study of the poor of eighteenth-century France, Olwen Hufton condemned poor relief as ‘grossly inadequate’, concluding that for most poor households, it formed no part of their ‘economy of makeshifts’. Historians have been quick to echo Hufton. Comparisons of social spending for different areas of Europe have contributed to a north-south divide whereby England in particular and the Low Countries are perceived as relatively generous while France and Spain were not. It is assumed that what limited relief existed in these latter countries was concentrated in towns, leading to a mass influx of beggars from the countryside. The lack of provision is attributed to extended family structures and supposedly closer family ties which obviated the need for poor relief.

My research seeks to explore and challenge these assumptions. The project addresses three core questions:

- What types of welfare provision existed in rural areas, and how can differences in the extent and nature of provision be explained?

- How far did responses to poverty change over the period?

- How adequate or generous was such poor relief?

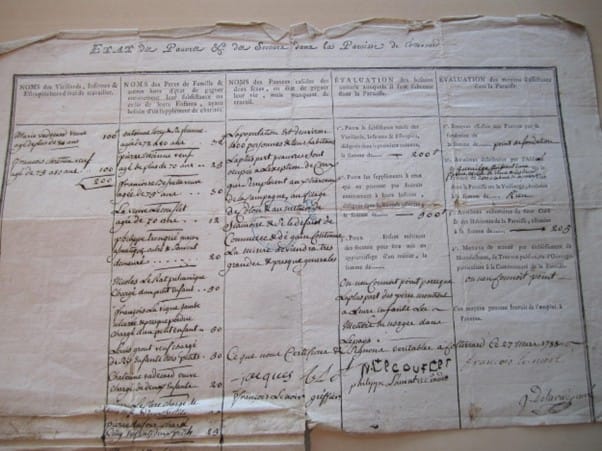

It does so through four case studies: an area of northern France around Rouen and Amiens, an area of southern France around Nîmes and Montpellier, an area of northern Spain (Catalonia) around Barcelona and an area of central Spain (Castile) around Toledo. These represent four regions with different economic, social, demographic and administrative structures, allowing for an analysis of how poor relief functioned in different contexts. Within these regional case studies, the investigation will look in-depth at individual parishes or communities with detailed records of charities.

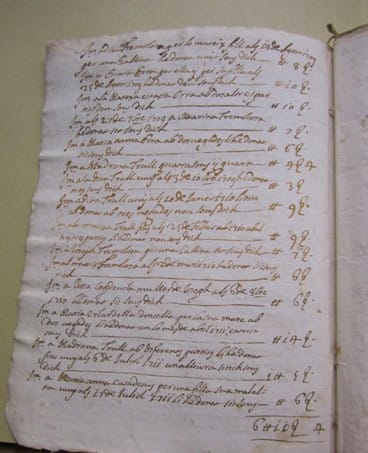

There were in fact many forms of poor relief in rural areas, such as dowry funds, bread doles, almsgiving, aid from confraternities and shelter in local hospitals. Historians have recognised their existence, but have tended to portray them as relics of a medieval past, inadequate in terms of the sums transferred to the poor and indiscriminate in the ways in which funds were distributed. By focusing on the late eighteenth century, historians have inevitably pointed to a ‘crisis of charity’ as growing numbers of the poor placed a strain on resources. Earlier charitable impulses in the seventeenth century are seen as short-lived. Moreover, attention has been focused on more ‘formal’ kinds of relief: endowments and hospitals, where there were legal and administrative frameworks and thus more source material. More ‘informal’ relief, such as almsgiving, which was often ad hoc and less likely to be recorded, has had less attention even though it may have been more important than formal relief in rural areas.

The project will map out as systematically as possible the different types of poor relief that existed in each of the four regions alongside other variables such as population, landholding, local economy, types of settlement and family and kinship structures, and investigate reasons for the relative importance of these across space and their survival or not over roughly two centuries. Above all, with recent work on the Low Countries in mind, I will examine the extent to which regions undergoing an early transition to capitalism and the growth of rural industry (Catalonia, northern France) saw more rapid and profound changes in poor relief structures than areas that did not (Castile, southern France).

‘Adequate’ and ‘generous’ have been defined in financial terms, often rather unsatisfactorily as a percentage of GDP per head, and focusing on ‘formal’ relief. Rather than defining ‘adequate’ or ‘generous’ in terms of GDP per capita, I will attempt to assess how far different forms of relief, ‘formal’ and ‘informal’, contributed to the household economies of the poor, and their relative importance alongside other resources, such as common rights, or seasonal work. Surprisingly, the question of why poor relief might have been ‘inadequate’ is rarely posed, let alone answered, beyond rather vague assumptions that there was a lack of will and vision. I will therefore investigate the obstacles to the funding and administration of poor relief, looking at who administrators were, and what legal frameworks existed to ensure both income and expenditure could be maintained.

Finally, the project broadens the notion of ‘adequate’ to consider issues of social cohesion. Giving to the poor has long been viewed in terms of reciprocity: charity was exchanged for deference. If we assume that poor relief was absent or inadequate, this begs questions about social relations in rural parishes. How was stability maintained, if the poor could not expect help from above? Here, the main focus will be on the nature of such gifts: the relationships between donors and recipients such as ties of kinship, landownership and tenure, master-servant relationships, and the assumptions of duty and custom that underpinned such gifts. The Carnevali grant will enable a pilot study of various archives and lay the ground for a bigger grant application.

To contact the author:

Julie Marfany

@juliemarfany

University of Durham