Economic Nationalism and the Scramble for Critical Minerals

In this blog post Andrew Perchard (Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka/University of Otago), Roy M. MacLeod (University of Sydney) and Jeremy Mouat (University of Alberta) present their research, which was supported by the Economic History Society through the Carnevali Small Research Grant.

—

Readers can scarcely have escaped the increasing global tensions around access to critical and strategic minerals, from so-called Rare Earth Elements to cobalt, coltan, lithium (vital for electronics, renewable energy and defence), as well as a range of other ferrous and non-ferrous ores (equally vital for defence, industry and infrastructure), reaching a crescendo with the Trump administration’s intervention in Venezuela, their demands over Ukrainian mineral reserves, and ramping threats to annex Greenland. In 2013, the former Chief Economist of Rio Tinto and Norilsk Nickel David Humphreys ventured that we were witnessing a ‘New Mercantilism’ with several countries, most notably China, involved in a zero-sum game to control the supply of metallic ores. A decade later, policymakers globally are taking threats to minerals supply chains far more seriously; in the last five years, the EU, UK and US, amongst others have scrambled to develop critical materials strategies and supply chain agreements.

Drawing on over a decade’s research in business and government archives and personal business and political papers, and supported by a 2015 Carnevali small research grant, alongside funding from the Australian Research Council, the Centre for Business History in Scotland, the US Science Foundation, and the Humboldt Foundation, this post accompanies the publication of our study (Perchard, MacLeod & Mouat, 2026) into the development of a British imperial minerals strategy during the First World War and its subsequent pursuit during the interwar years of 1919-1939 as part of a special issue of Business History on globalisation, economic nationalism and big business.

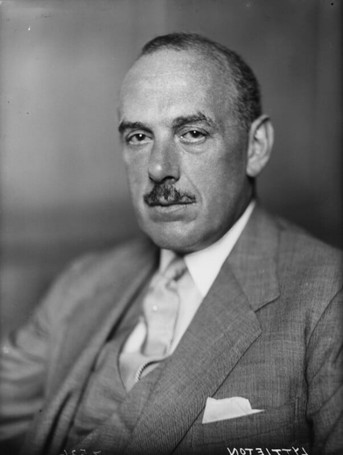

This strategy sought to combine intelligence gathering on minerals reserves and trade within the British Empire and ensure British capital was available to control those reserves through the formation of two bodies in 1918; the Imperial Minerals Resources Bureau (IMRB) and the British Metals Corporation (BMC). Previous accounts of the latter (Becker, 1997; Ball, 2004) have emphasized this as a metropolitan British power initiative driven by fears of the German stockpiling of metallic ores from the British Empire, undertaken by what was pungently referred to in the fevered atmosphere of the First World War as the ‘German Octopus’ of German metals traders Metalgesellschaft and its British subsidiary Henry R. Merton & Sons Ltd. Our study acknowledges the role of metropolitan British actors – politicians and business leaders alike, such as Oliver Lyttelton (later Lord Chandos) – but highlights the importance of other imperial actors driving this strategy, most notably Australia’s wartime Prime Minister William Morris ‘Billy’ Hughes and Australian industrialists like William Sydney Robinson and William Baillieu of the Collins House Group and the Broken Hill mining companies, in advancing this strategy, driven both by fears about German purchasing of ores that pre-dated the outbreak of war in 1914 and because of the nation-building opportunities. We also explore the conflicting interests and objections of a Canadian government to this strategy, concerned about restrictions this might impose on the flow of materials and capital across the 49th parallel and about British imperial overreach.

Despite its immediate effectiveness, the increasing complexity of imperial politics during the interwar years, and divergences in policy and unwillingness to fund this intergovernmental organization, led to the winding up of the IMRB in 1925 and its absorption into the Imperial Institute. Our article demonstrates subsequently how vital the BMC became to the continued pursuit of an imperial minerals strategy, underlain by a network of constituent firms and networks of industrialists and politicians spread across the empire. BMC and associated firms fulfilled the role of non-state actors; a concept borrowed from international relations to describe actors who are not the state but pursue actions on their behalf when the latter is unable to do so. The success of that strategy hinged was reliant upon a network of industrialists, politicians, and civil servants, who enjoyed the necessary knowledge, social capital and goodwill to move between the fields of business and politics. This strategy was ultimately crucial in ensuring Britain and the empire had sufficient supplies of the strategic raw materials that it required to prosecute another prolonged industrial war between 1939 and 1945 and avoid the supply crises of the First World War. As after Lloyd George’s reorganisation of the Ministry of Munitions in 1916, it was these same industrialists who took office during the Second World War to oversee minerals supply.

To contact the authors:

Andrew Perchard

Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand

Roy M. MacLeod

University of Sydney, Australia

Jeremy Mouat

University of Alberta, Canada

References:

Ball, S., ‘“The German Octopus”: The British Metal Corporation and the Next War, 1914 – 1939’, Enterprise & Society, 53 (2004), pp.451 – 489.

Becker, S., ‘The German metals traders before 1914’, in G. Jones, ed., The Multinational Traders (London, 1998), pp.66 -85.

Humphreys, D., ‘New mercantilism: A perspective on how politics is shaping world metal supply’, Resources Policy, 38, 3 (2013), pp.341 – 349.

Perchard, A., MacLeod, R. M., and Mouat, R. (2026). ‘British Empire in Metals’: Non-state actors and the political economy of imperial minerals, 1913 – 1939. Business History (2026). Online First, DOI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00076791.2025.2606356#ack