Fascist Policy and the Great Depression in Italy

This blog is based upon the research funded by a grant awarded by the Economic History Society through its Research Fund for Graduate Students to Gino Magnini of the University of Edinburgh. In this post they introduce their research.

—

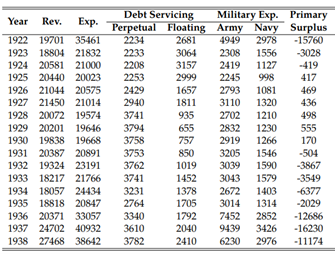

Most of the academic literature on the consequences of the Great Depression in Fascist Italy usually describe the downturn as less accentuated and of shorter duration than those in other Western countries. Although the crisis was relatively less severe than in other countries, recent work on Italy’s national accounts and other metrics shows that it prolonged well into the late 1930s. Although it is often argued that loose fiscal policy and the departure from the gold standard brought an end to the crisis in many countries, Fascist Italy was characterized by both. The Fascist government was running consistently larger deficits since 1926 and the Italian Lira was no longer on a gold standard by the end of 1933.

Accordingly, my project aims at answering some of the questions arising from these contradictions by looking at the broader interwar period. In particular, the early quantitative evidence gathered in my research efforts, partially funded by the EHS Research Fund, seemed to show that for the great majority of the 1930s, the performance of Italy’s economy was blighted by three main economic indicators: persistent labor inactivity, stagnating productivity rates and increasing interest rates on private credit. As a result, industrial value added and worked hours at industrial plants remained below pre-crisis levels until 1937-38. Industrial output at constant prices only recovered from the downturn in 1938. Meanwhile, firms were having a difficult time raising capital for investment due to the increasing costs of borrowing which further impeded industrial productivity growth.

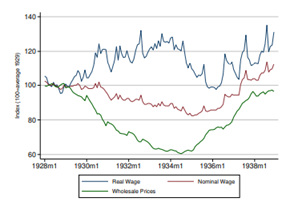

The labor reforms introduced by the Fascist government in 1926-27 played a vital role in labor allocation in the agricultural and industrial sectors by enforcing regional and national collective contracts. Wages were set by these agreements by the rulings of labor courts and all employers and employees within a given sector or industry had to abide to it. Employers could no longer offer their desired wage rate whilst employees had to accept the dispositions of collective labor contracts. Disputes over wage changes were often resolved in labor courts where officials appointed by the government decided on these cases with repercussions across whole regions and industries. Since the wage-setting mechanism employers could no longer adjust wages and, therefore, struggled to reduce costs of production according to their needs. When depressed aggregate demand and deflation hit companies in the early 1930s, employers found it easier to lay off employees in order to control production costs given their inability to change wages. Data on nominal and real wages in the industrial sector in the 1930s show exactly what one would expect – real wages appreciating as nominal wages could not keep up with falls in prices. The prolonged periods of unemployment and increasing real wages forced many workers out of the workforce and into inactivity, as reported in the population census in the 1930s.

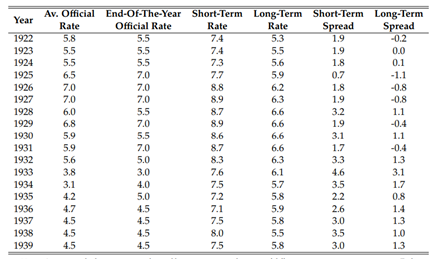

Another important drag on the Italian economy was the increasing borrowing costs of private funds. This was the result of a large contraction in the stock of national savings and declining savings rates. The consequence of a contraction in the supply of funds and the rationing of credit was the inevitable increase in the price of private credit. However, these phenomena were not exclusive to the 1930s as some evidence on savings suggests in the late 1920s. Moreover, the increase in borrowing costs during the 1930s took place in an environment of decreasing discount rates set by the central bank. The stock of paper money in circulation also drastically increased after 1933 but the spread between official discounting rates and interest rates charged by banks continued increasing. The main drain on national saving and the crowding out of private investment was the loose fiscal policy pursued by the government in the 1930s. The government not only issue national loans to restructure and consolidate the country’s debt, but also began large national programs of subsidies, social insurances and rearmament. The nationalization of Italy’s biggest banks in 1933 only worsened the trend, locking up the great majority of national savings in the hands of the state and the impossibility of borrowing to industries.

The Great Depression was relatively more persistent in Italy than in other Western countries, especially considering its early departure from the gold standard and its lax fiscal policy. The reason for this has to be attributed in the structures of the Italian economy and the adverse effect of policies pursued by the Fascist government. In particular, labor market reforms produced high inactivity levels and falling hours worked, whilst fiscal policy crowded out private investment.

To contact the author:

Gino Magnini

Gino.Magnini@ed.ac.uk

Twitter/X: @ginomagnini

University of Edinburgh