Fascistville: Mussolini’s new towns and the persistence of neo-fascism

by Mario F. Carillo (CSEF and University of Naples Federico II)

This blog is part of our EHS 2020 Annual Conference Blog Series.

—

Differences in political attitudes are prevalent in our society. People with the same occupation, age, gender, marital status, city of residence and similar background may have very different, and sometimes even opposite, political views. In a time in which the electorate is called to make important decisions with long-term consequences, understanding the origins of political attitudes, and then voting choices, is key.

My research documents that current differences in political attitudes have historical roots. Public expenditure allocation made almost a century ago help to explain differences in political attitudes today.

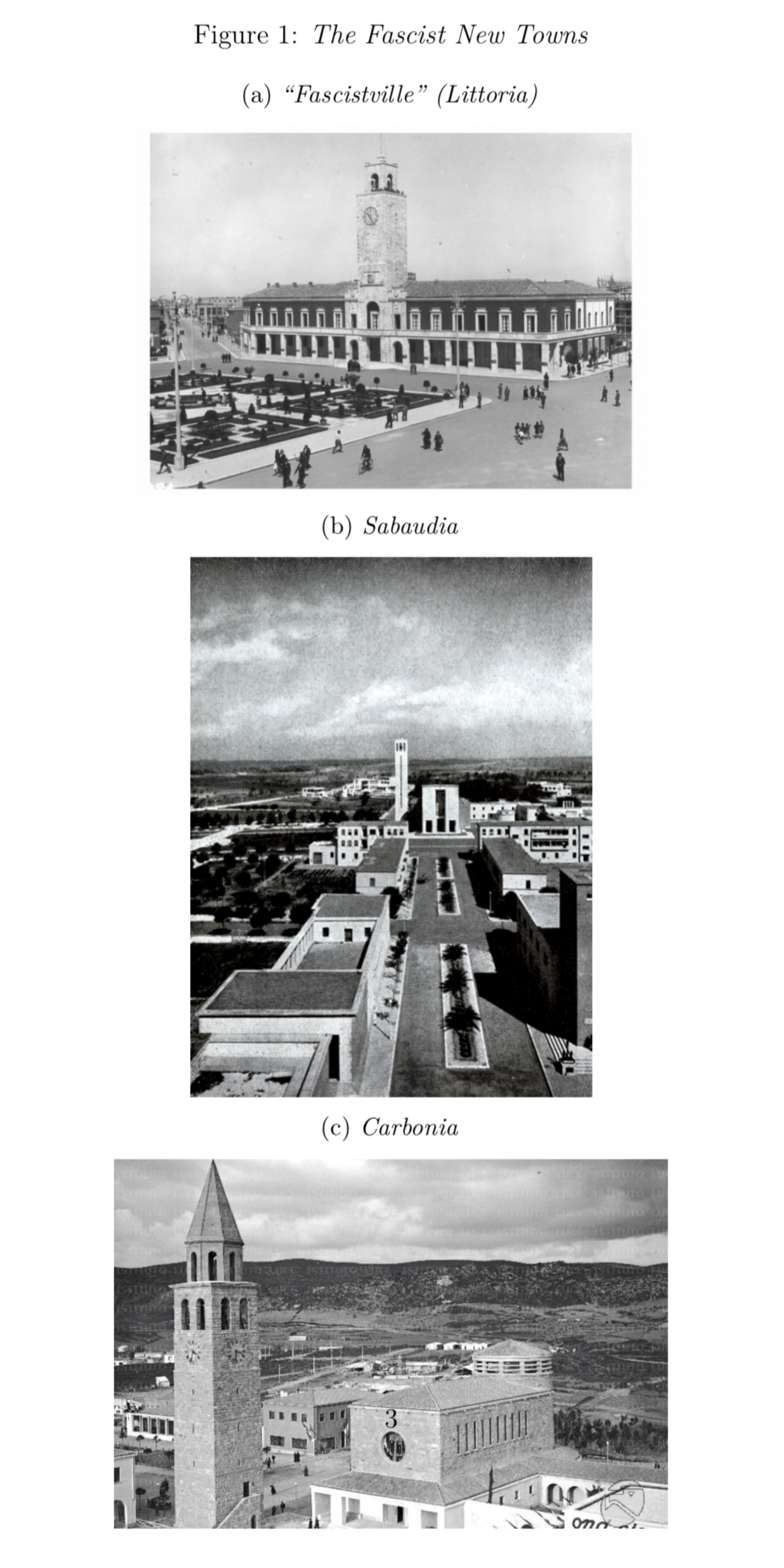

During the Italian fascist regime (1922-43), Mussolini undertook enormous investments in infrastructure by building cities from scratch. Fascistville (Littoria) and Mussolinia are two of the 147 new towns (Città di Fondazione) built by the regime on the Italian peninsula.

Towers shaped like the emblem of fascism (Torri Littorie) and majestic buildings as headquarters of the fascist party (Case del Fascio) dominated the centres of the new towns. While they were modern centres, their layout was inspired by the cities of the Roman Empire.

Intended to stimulate a process of identification of the masses based on the collective historical memory of the Roman Empire, the new towns were designed to instil the idea that fascism was building on, and improving, the imperial Roman past.

My study presents three main findings. First, the foundation of the new towns enhanced local electoral support for the fascist party, facilitating the emergence of the fascist regime.

Second, such an effect persisted through democratisation, favouring the emergence and persistence of the strongest neo-fascist party in the advanced industrial countries — the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI).

Finally, survey respondents near the fascist new towns are more likely today to have nationalistic views, prefer a stronger leader in politics and exhibit sympathy for the fascists. Direct experience of life under the regime strengthens this link, which appears to be transmitted across generations inside the family.

Thus, the fascist new towns explain differences in current political and cultural attitudes that can be traced back to the fascist ideology.

These findings suggest that public spending may have long-lasting effects on political and cultural attitudes, which persist across major institutional changes and affect the functioning of future institutions. This is a result that may inspire future research to study whether policy interventions may be effective in promoting the adoption of growth-enhancing cultural traits.