From Records to Riches – An Automated Pipeline for Transcribing the Tables des Successions et Absences, 1790-1870

In this blog post, Aurelius Noble and Noah Sutter of the London School of Economics introduce their research, which was financially supported by a Carnevali Small Research Grant.

—

The Long Nineteenth Century was a period of revolution in France. Both politically and economically. The revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848 were followed by a period of industrialisation. How profoundly these revolutions have affected the social status of the old regime elites is still a subject of study. Studies on the long-run persistence of wealth and status in England, like Clark and Cummins (2014b, 2014a, 2015) find that elite status and wealth seem to be much more persistent than previously assumed. On the face of it, France seems to be a very different case: repeated political revolutions instead of relative political stability and an absence of a gentlemanly capitalism (Cain and Hopkins, 1986)[1]. Given the place of 1789 in the popular imagination, we might expect to see dramatic changes in the wealth distribution caused by the Revolution. The reality is likely to be more ambiguous. The social mobility effects of the revolution have long been the subject of scholarly debate. While Marxist or Marxisant explanations of the Revolution of 1789 (Jaurès, 1924; Lefebvre, 1947; Soboul, 1953) have emphasized the economic ascent of the capitalist class – and its corollary – the decline of the aristocracy, more recent scholarship (Forster, 1967; Beck, 1981; Aftalion, 1990; Tackett, 1996; Van Leeuwen et al., 2016) failed to find such a ”revolutionary bourgeoisie” economically overtaking the nobility. Mayer (1981) argues that the Old Regime was much more persistent because most of continental European wealth still took the form of land, which was not really affected by the political revolutions. A growing literature in economics highlights the surprising persistence of elite wealth in times of revolution (Alesina et al., 2020; Ager et al., 2021). With this project we want to make use of a new dataset to shed new light on this longstanding question.

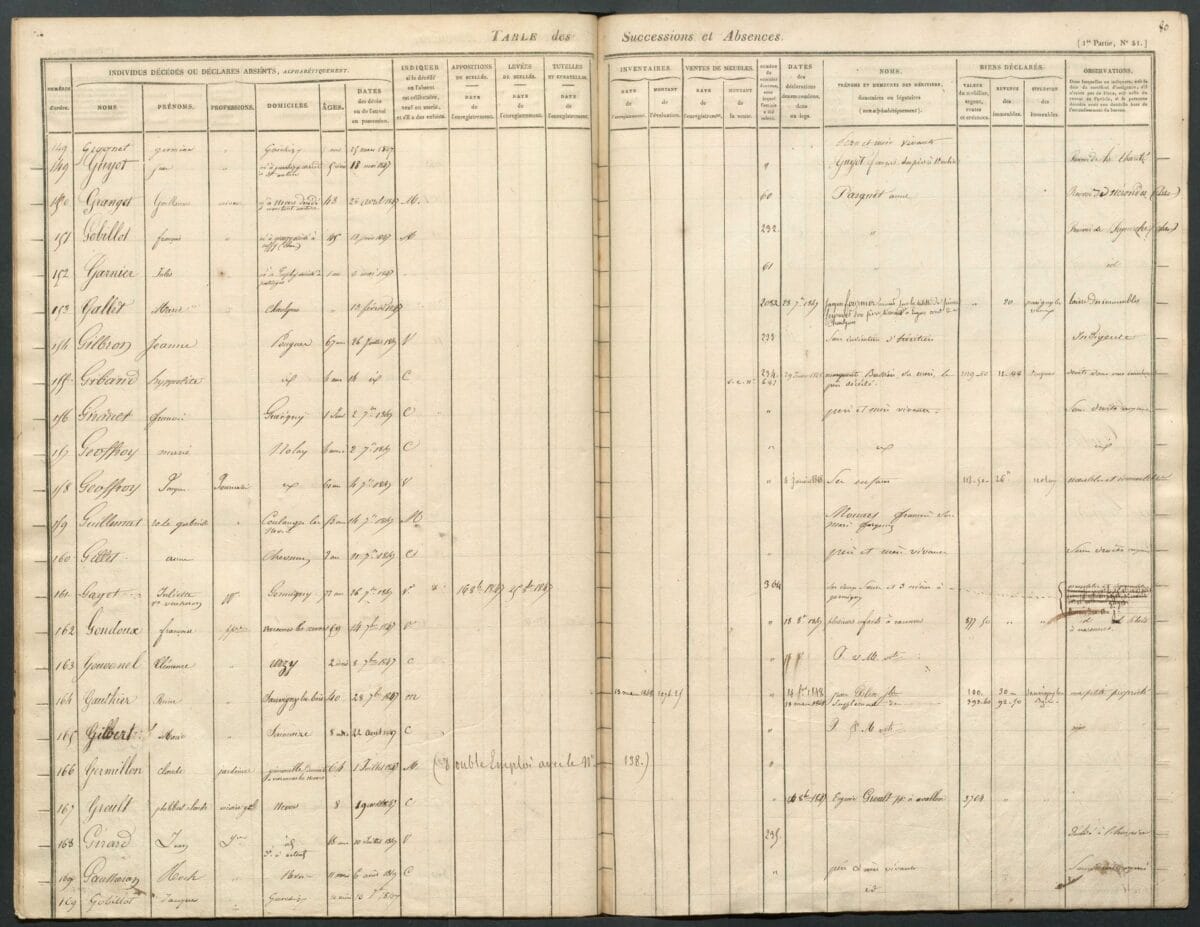

In order to do so, we aim at digitising parts of the so-called Tables des Successions et Absences (TSA). The TSA are a unique source for the study of the historical wealth distribution. They were born out of the desire of the revolutionary legislature to reinvent the fiscal system in a way that would both pay justice to the revolutionary principles of equality and universality, as well as help implement the new regime of the family – the equal treatment of all children of a household (Bourdieu et al., 2014, p. 61 ff.). The result was a universal, non-progressive wealth tax, levied at the individual level at death. Wealth and information on the deceased were meticulously recorded, controlled, and audited. Adhering to the principles of universality and equality implied that even the wealth of the poorest was assessed and – even if only a few francs – taxed and recorded. It also implied a levy at the individual level, which includes women and children. Such a universal degree of coverage is exceptional for the period in question. In 1870, with the establishment of the Third Republic, the TSA stopped recording wealth at death, as wealth was henceforth to be recorded in the so-called Répertoire Général.

In order to be able to use this extraordinary source, we have built an end-to-end pipeline that employs state-of-the-art open-source technology at every step. The pipeline is able to process the images of the handwritten pages and to convert them to tabular data on individual-level wealth at death. First, text lines are detected using the model Doc-UFCN (Boillet et al., 2021). Second, these text lines are then transcribed using a transformer-based handwritten text recognition model called TrOCR (Li et al., 2023). Finally, using a combination of Doc-UFCN and computer vision, the page is then segmented into columns and rows. This can then be used to reconstruct the positioning of the text lines – i.e. the strings of information – within the tabular structure of the page.

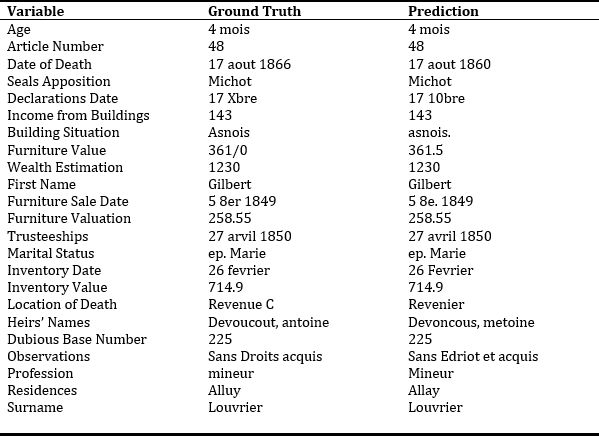

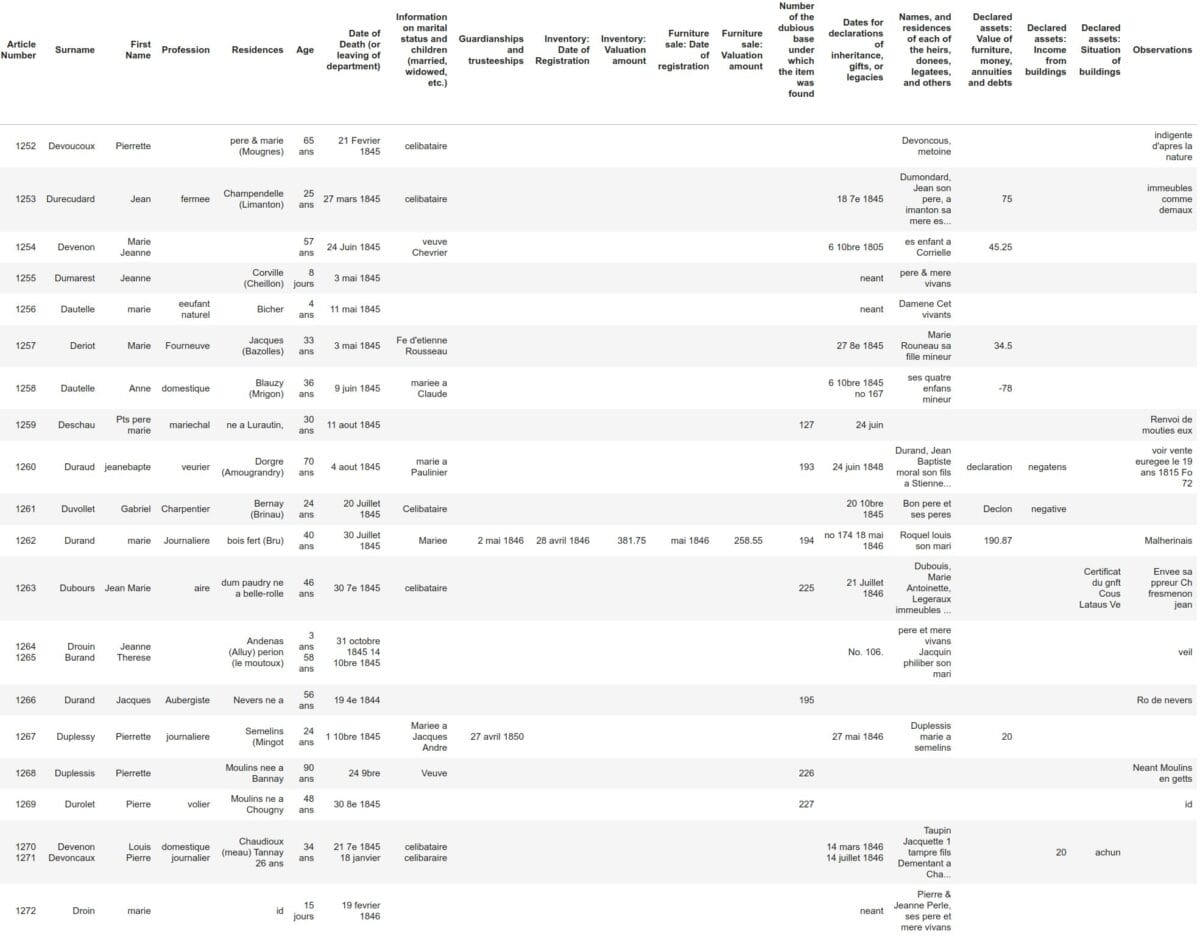

Using data from the rural Département de la Nièvre, we have conducted a pilot study and have achieved very promising results. Figure 2 shows the transcription result corresponding to the median character error rate (CER) for each column in our dataset. As can be seen, transcription of the eighteenth and nineteenth century handwriting is exceptionally reliable. In many cases the median CER is zero and the model’s prediction exactly corresponds to the ground truth. Even in cases where ground truth and prediction do not correspond, the differences are often not still conveying the exact same meaning as in the ground truth. Figure 3 presents the final output of our pipeline: a fully transcribed page. This page represents the median outcome, with its character error rate (CER) per column aligning with the median value among all results.

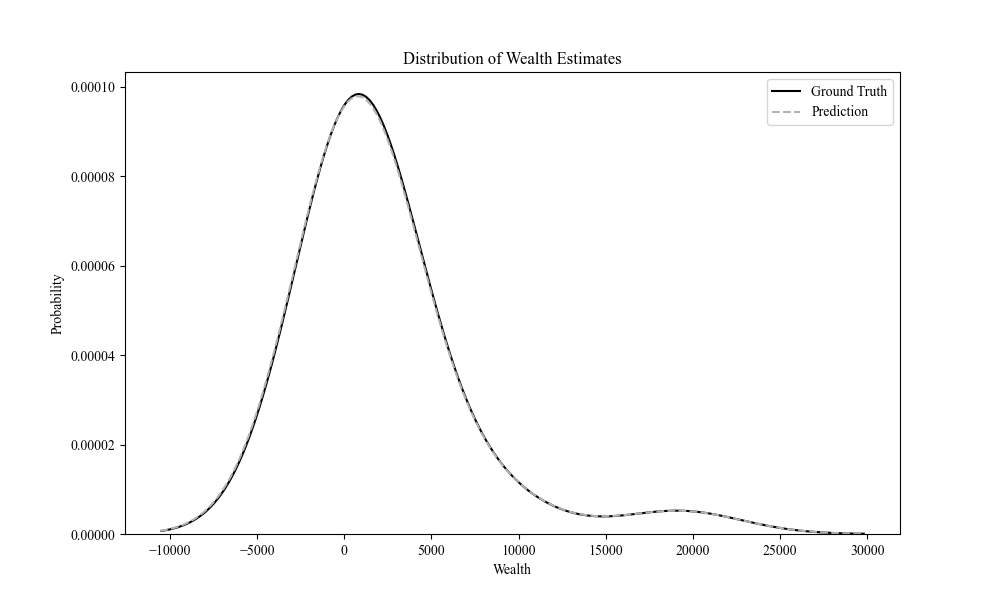

The processing of numbers is a special challenge for us. Recognition of individual numerical characters may sometimes be easier for text recognition models than recognition of individual alphabetical characters due to numerical characters’ very distinct shapes. A significant challenge with numerical recognition is posed by the lack of contextual cues. For words, linguistic and spelling rules can help identify and correct errors, but similar mechanisms are absent for numerical data. Even small character error rates in numerical strings can be difficult to detect and correct, as there are no grammatical or syntactical patterns to rely on for error detection. Since wealth at death is crucial information for us – and is recorded as numerical string – it is crucial that the model performs well. As we can see in Figure 4, our model performs very well. The predicted wealth distribution closely matches the ground truth wealth distribution of our evaluation dataset.

As a next step, we want to digitise more and more of the available data to explore the social mobility and inequality conference of this fascinating period of institutional and cultural change. One particular focus of attention will be the introduction of equal partition by the Code Napoléon – something which set France apart from England where aristocratic estates were still inherited via primogeniture.

Footnotes:

[1] A somewhat dissenting position is offered by Chaussinand-Nogaret (1976), who argues that the 18th century nobility were the most dynamic part of society and were heavily involved wherever early forms of modern high capitalism were emerging.

To contact the authors:

Aurelius Noble

a.j.noble@lse.ac.uk

@AureliusNoble

Department of Economic History, LSE

Noah Sutter

n.w.sutter@lse.ac.uk

@NoahWSutter

Department of Economic History, LSE

References:

Aftalion, F. (1990). The French Revolution: an economic interpretation. Cambridge University Press.

Ager, P., Boustan, L., and Eriksson, K. (2021). The intergenerational effects of a large wealth shock: white southerners after the civil war. American Economic Review, 111(11):3767–3794.

Alesina, A., Seror, M., Yang, D. Y., You, Y., Zeng, W., et al. (2020). Persistence through revolutions. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Beck, T. (1981). The french revolution and the nobility: a reconsideration. Journal of Social History, 15(2):219– 233.

Boillet, M., Kermorvant, C., and Paquet, T. (2021). Multiple Document Datasets Pre-training Improves Text Line Detection With Deep Neural Networks. In 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), pages 2134–2141.

Bourdieu, J., Kesztenbaum, L., and Postel-Vinay, G. (2014). L’enquête TRA, histoire d’un outil, outil pour l’histoire: Tome I. 1793-1902. INED.

Cain, P. J. and Hopkins, A. G. (1986). Gentlemanly capitalism and british expansion overseas i. the old colonial system, 1688-1850. Economic History Review, pages 501–525.

Chaussinand-Nogaret, G. (1976). La Noblesse au XVIIIe siècle: de la féodalité aux lumières. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

Clark, G. and Cummins, N. (2014a). Inequality and social mobility in the era of the industrial revolution. The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, 1:211–236.

Clark, G. and Cummins, N. (2014b). Surnames and social mobility in england, 1170–2012. Human Nature, 25(4):517–537.

Clark, G. and Cummins, N. (2015). Intergenerational wealth mobility in england, 1858–2012: surnames and social mobility. The Economic Journal, 125(582):61–85.

Forster, R. (1967). The survival of the nobility during the french revolution. Past & Present, (37):71–86.

Jaurès, J. (1924). Histoire socialiste de la Révolution française, volume 7. Éditions de la Librairie de l’humanité. Lefebvre, G. (1947). The coming of the French Revolution. Princeton University Press Princeton.

Li, M., Lv, T., Chen, J., Cui, L., Lu, Y., Florencio, D., Zhang, C., Li, Z., and Wei, F. (2023). Trocr: Transformer- based optical character recognition with pre-trained models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 37, pages 13094–13102.

Mayer, A. J. (1981). The persistence of the old regime: Europe to the Great War. Pantheon Books.

Soboul, A. (1953). Classes and class struggles during the french revolution. Science & Society, pages 238–257.

Tackett, T. (1996). Becoming a revolutionary: the deputies of the French National Assembly and the emergence of a revolutionary culture (1789-1790). Princeton University Press.

Van Leeuwen, M. H., Maas, I., Rébaudo, D., and Pélissier, J.-P. (2016). Social mobility in france 1720–1986: Effects of wars, revolution and economic change. Journal of Social History, 49(3):585–616.