from VOX – Men

by Victoria Baranov (University of Melbourne), Ralph De Haas (EBRD, CEPR, and Tilburg University) and Pauline Grosjean (University of New South Wales). More information on the authors below.

The content of this article was originally published on VOX and has been published here with the authors’ consent.

Why are men three times as likely than women to die from suicide? And why do many unemployed men refuse to apply for jobs that are typically done by women? This column argues that a better understanding of masculinity norms – the rules and standards that guide and constrain men’s behavior in society – can help answer important questions like these. We present evidence from Australia on how historical circumstances have instilled strong and persistent masculine identities that continue to influence outcomes related to male health; violence, suicide, and bullying; attitudes towards homosexuals; and occupational gender segregation.

What makes a ‘real’ man? According to traditional gender norms, men ought to be self-reliant, assertive, competitive, violent when needed, and in control of their emotions (Mahalik et al., 2003). Two current debates illustrate how such masculinity norms have profound economic and social impacts. First, in many countries, men die younger than women and are consistently less healthy. Masculinity norms, especially a penchant for violence and risk taking, are an important cultural driver of this gender health gap (WHO, 2013). A second debate links masculinity norms to occupational gender segregation. Technological progress and globalization have disproportionately affected male employment. Yet, many newly unemployed men refuse to fill jobs that do not match their self-perceived gender identity (Akerlof and Kranton, 2000).

The extent to which men are expected to conform to stereotypical masculinity norms nevertheless differs across societies. This raises the question: where do masculinity norms come from? The origins of gender norms about women have been the focus of a vibrant literature (Giuliano, 2018). By contrast, the origins of norms that guide and constrain the behavior of men have received no attention in the economics literature.

In recent research, we argue that strict masculinity norms can emerge in response to highly skewed sex ratios (the number of males relative to females) which intensify competition among men (Baranov, De Haas and Grosjean, 2020). When the sex ratio is more male biased, male-male competition for scarce females is more intense. This competition can intensify violence, bullying, and intimidating behavior (e.g. bravado), which, once entrenched in local culture, continue to manifest themselves in present-day outcomes long after sex ratios have normalized. We test this hypothesis using data from a unique natural experiment: the convict colonization of Australia.

Australia as a historical experiment

To establish a causal link from sex ratios to the manifestation of masculinity norms, we exploit the convict colonization of Australia. Between 1787 and 1868, Britain transported 132,308 convict men but only 24,960 convict women to Australia. Convicts were not confined to prisons but allocated across the colonies in a highly centralized manner. This created a variegated spatial pattern in sex ratios, and consequently in local male-to-male competition, in an otherwise homogeneous setting.

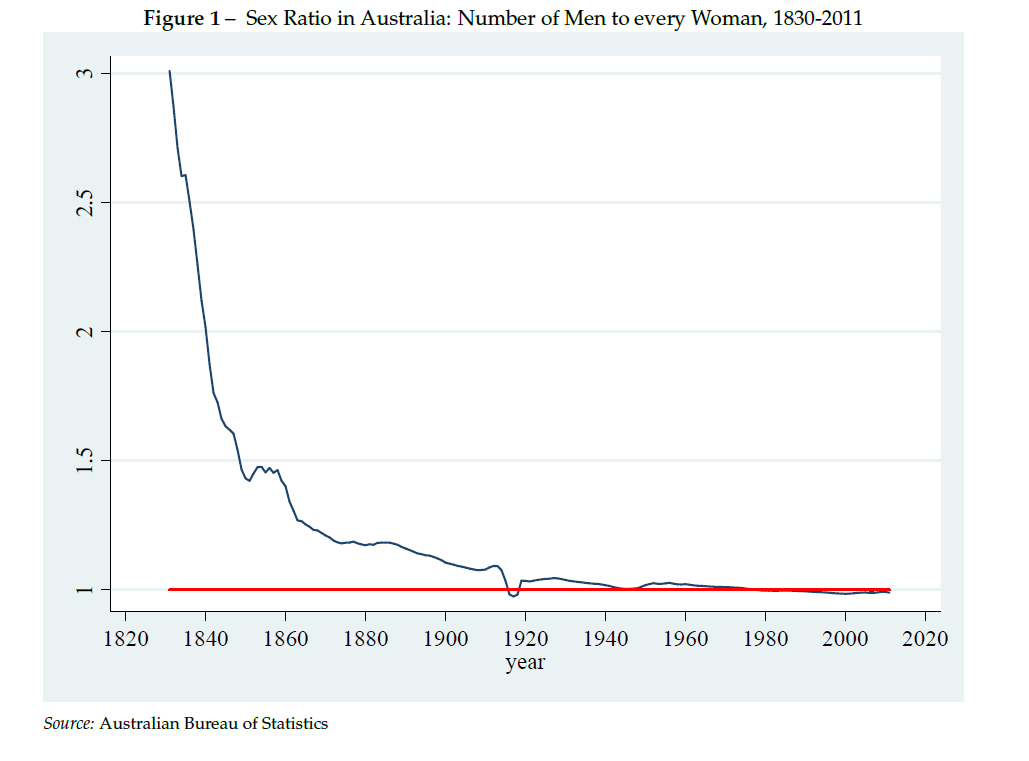

Convicts and ex-convicts represented the majority of the colonial population in Australia well into the mid-19th century. Voluntary migration was limited and mainly involved men migrating in response to male-biased economic opportunities available in agriculture and, after the discovery of gold in the 1850s, mining. Because of the predominance of male convicts and migrants, biased population sex ratios endured for over a century (Figure 1).

Identifying the lasting impact of skewed sex ratios

We regress present-day manifestations of masculinity norms, including violent behavior, bullying, and stereotypically male occupational choice on historical sex ratios, collected from the first reliable census in each Australian state (see also Grosjean and Khattar, 2019). An empirical challenge is that variation in historical sex ratios could reflect unobservable characteristics. To tackle this, we instrument the historical sex ratio by the sex ratio among convicts only. This instrument is highly relevant since most of the white Australian population initially consisted of convicts. Moreover, convicts were not free to move: a centralized assignment scheme determined their location as a function of labor needs, which we control for by initial economic specialization. Throughout the analysis, we also control for time-invariant geographic and historic characteristics as well as key present-day controls (sex ratio, population, and urbanization).

Masculinity norms among Australian men today

Using the above empirical strategy, we derive four sets of results:

1. Violence, suicide, and health

We first assess the impact of historically skewed sex ratios on present-day violence and health outcomes. Evidence suggests that men adhering to traditional masculinity norms attach a stronger stigma to mental health problems and tend to avoid health services. As a proxy for the avoidance of preventative health care we use local suicide and prostate cancer rates. Prostate cancer is often curable if treated early, but avoidance of diagnosis is a public health concern. The endorsement of strict masculinity norms is also associated with aggression, excessive drinking, and smoking.

Our estimates show that today, the rates of assault and sexual assault are higher in parts of Australia that were more male biased in the past. A one unit increase in the historical sex ratio (defined as the ratio of the number of men over the number of women) is associated with an 11 percent increase in the rate of assault and a 16 percent increase in sexual assaults. We also find strong evidence of elevated rates of male suicide, prostate cancer, and lung disease in these areas. For male suicide – the leading cause of death for Australian men under 45 – a one unit increase in the historical sex ratio is associated with a staggering 26 percent increase.

2. Occupational gender segregation

A second manifestation of male identity is occupational choice. Our results paint a striking picture. A one unit increase in the sex ratio is associated with a nearly 1 percentage point shift from the share of men employed in neutral (e.g. real estate, retail) or stereotypically female occupations (e.g. teachers, receptionists) to stereotypically male occupations (e.g. carpenters, metal workers).

3. Support for same-sex marriage

We capture the political expression of masculine identity by opposition against same-sex marriage, which we measure using voting records from the nation-wide referendum on same-sex marriage in 2017. Our results show that the share of votes in favor of marriage equality is substantially lower in areas where sex ratios were more male biased in the past. A one unit increase in the historical sex ratio is associated with a nearly 3 percentage point decrease in support for same-sex marriage. This is slightly over 6 percent of the mean.

4. Bullying

Lastly, we find that boys, but not girls, are more likely to be bullied at school in areas that used to be more male biased in the past. The magnitude of the results is considerable and in line with the magnitude of the results for assaults (measured in adults). A one unit increase in the historical sex ratio is associated with a higher likelihood of parents (teachers) reporting bullying of boys by 13.7 (5.2) percentage points. This suggests that masculinity norms are perpetuated through horizontal transmission: peer pressure, starting at a young age in the playground.

Conclusions

We find that historically male-biased sex ratios forged a culture of male violence, help avoidance, and self-harm that persists to the present day in Australia. While our experimental setting is unique, we believe that our findings can inform the debate about the long-term socioeconomic consequences and risks of skewed sex ratios in many developing countries such as China, India, and parts of the Middle East. In these settings, sex-selective abortion and mortality as well as the cultural relegation and seclusion of women have created societies with highly skewed sex ratios. Our results suggest that the masculinity norms that develop as a result may not only be detrimental to (future generations of) men themselves but can also have important repercussions for other groups in society, in particular women and sexual minorities.

Our findings also align with an extensive psychological and medical literature that connects traditional masculinity norms to an unwillingness among men to seek timely medical help or to engage in preventive health care and protective health measures (e.g. Himmelstein and Sanchez (2016) and Salgado et al. (2016)). This suggests that voluntary observance of health measures, such as social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, may be considerably lower among men who adhere to traditional masculinity norms.

References

Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton (2000), Economics and Identity, Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3), 715–753.

Baranov, Victoria, Ralph De Haas and Pauline Grosjean (2020), Men. Roots and Consequences of Masculinity Norms, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 14493, London.

Giuliano, Paola (2018), Gender: A Historical Perspective, The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, Ed. Susan Averett, Laura Argys and Saul Hoffman. Oxford University Press, New York.

Grosjean, Pauline, and Rose Khattar (2019), It’s Raining Men! Hallelujah? The Long-Run Consequences of Male-Biased Sex Ratios, The Review of Economic Studies, 86(2), 723–754.

Himmelstein, M.S. and D.T. Sanchez (2016), Masculinity Impediments: Internalized Masculinity Contributes to Healthcare Avoidance in Men and Women, Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 1283–1292.

Mahalik, J.R., B.D. Locke, L.H. Ludlow, M.A. Diemer, R.P.J. Scott, M. Gottfried, and G. Freitas (2003), Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory, Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 4(1), 3–25.

Salgado, D.M., A.L. Knowlton, and B.L. Johnson (2019), Men’s Health-Risk and Protective Behaviors: The Effects of Masculinity and Masculine Norms, Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20(2), 266–275.

WHO (2013), Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

Ralph De Haas, a Dutch national, is the Director of Research at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London. He is also a part-time Associate Professor of Finance at Tilburg University, a CEPR Research Fellow, a Fellow at the European Banking Center, a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Institute of Global Affairs at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and a Research Associate at the ZEW–Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research. Ralph earned a PhD in economics from Utrecht University and is the recipient of the 2014 Willem F. Duisenberg Fellowship Prize. He has published in the Journal of Financial Economics; Review of Financial Studies; Review of Finance; Journal of International Economics, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics; the Journal of the European Economic Association and various other peer-reviewed journals. Ralph’s research interests include global banking, development finance and financial intermediation more broadly. He is currently working on randomized controlled trials related to financial inclusion in Morocco and Turkey.

Twitter: @ralphdehaas

Pauline Grosjean is a Professor in the School of Economics at UNSW. Previously at the University of San Francisco and the University of California at Berkeley, she has also worked as an Economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. She completed her PhD in economics at Toulouse School in Economics in 2006 after graduating from the Ecole Normale Supérieure. Her research studies the historical and dynamic context of economic development. In particular, she focuses on how culture and institutions interact and shape long-term economic development and individual behavior. She has published research that studies the historical process of a wide range of factors that are crucial for economic development, including cooperation and violence, trust, gender norms, support for democracy and for market reforms, immigration, preferences for education, and conflict.

Victoria Baranov’s research explores how health, psychological factors, and norms interact with poverty and economic development. Her recent work has focused on maternal depression and its implications for the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. Her work has been published in the American Economic Review, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, the Journal of Health Economics and other peer-reviewed journals across multiple disciplines. Victoria received her PhD in Economics from the University of Chicago after graduating from Barnard College. She is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Economics Department at the University of Melbourne and has affiliations with the Centre for Market Design, the Life Course Centre, and the Institute of Labor Studies (IZA).

Twitter: @VictoriaBaranov