From VOX – Short poppies: the height of WWI servicemen

From Timothy Hatton, Professor of Economics, Australian National University and University of Essex. Originally published on 9 May 2014

The height of today’s populations cannot explain which factors matter for long-run trends in health and height. This column highlights the correlates of height in the past using a sample of British army soldiers from World War I. While the socioeconomic status of the household mattered, the local disease environment mattered even more. Better education and modest medical advances led to an improvement in average health, despite the war and depression.

The last century has seen unprecedented increases in the heights of adults (Bleakley et al., 2013). Among young men in western Europe, that increase amounts to about four inches. On average, sons have been taller than their fathers for the last five generations. These gains in height are linked to improvements in health and longevity.

Increases in human stature have been associated with a wide range of improvements in living conditions, including better nutrition, a lower disease burden, and some modest improvement in medicine. But looking at the heights of today’s populations provides limited evidence on the socioeconomic determinants that can account for long-run trends in health and height. For that, we need to understand the correlates of height in the past. Instead of asking why people are so tall now, we should be asking why they were so short a century ago.

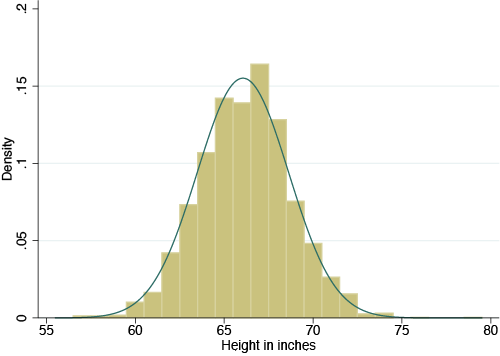

In a recent study Roy Bailey, Kris Inwood and I ( Bailey et al. 2014) took a sample of soldiers joining the British army around the time of World War I. These are randomly selected from a vast archive of two million service records that have been made available by the National Archives, mainly for the benefit of genealogists searching for their ancestors.

For this study, we draw a sample of servicemen who were born in the 1890s and who would therefore be in their late teens or early twenties when they enlisted. About two thirds of this cohort enlisted in the armed services and so the sample suffers much less from selection bias than would be likely during peacetime, when only a small fraction joined the forces. But we do not include officers who were taller than those they commanded. And at the other end of the distribution, we also miss some of the least fit, who were likely to be shorter than average.