Global shipping and the invisible limits of decolonisation in Eastern Africa

This blog presents research by George Roberts of the University of Sheffield which has recently been awarded a Carnevali Small Research grant by the Economic History Society.

—

Considered an ‘invisible’ cost by economists, international shipping remains absent in public conversation – until something goes wrong. But the global headlines generated by accidental blockages to the Suez Canal or attacks on Red Sea cargo shipping by pro-Palestinian forces in Yemen serve to demonstrate the geopolitical stakes involved in the sector. The success of Marc Levinson’s bestseller, The Box, illustrates the critical importance of shipping to contemporary globalisation. However, with its focus on the revolutionary impact of containerisation and a perspective narrated from the United States, The Box overlooks alternative histories of twentieth-century shipping, especially in the Third World. As Laleh Khalili recognises in Sinews of War and Trade, the evolution of modern shipping has been tightly bound up with projects of colonial control.

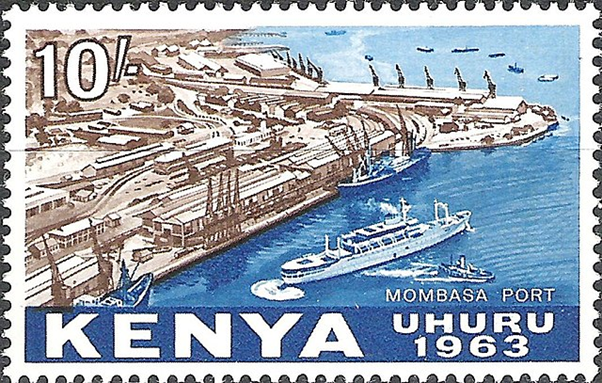

As waves of postwar decolonisation transformed the map of the world, leaders of newly independent nations recognised the importance of shipping to their own projects of economic decolonisation. Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana, a self-styled revolutionary spearhead in Africa, set up its own Black Star Line to challenge Western colonial-era cargo companies. On the continent’s eastern coast, politicians and economists discussed similar initiatives. Rather than establish their own individual lines, East Africa’s governments seized on a moment of regional integration at the high tide of decolonisation to embark on a joint venture. Kenya and Tanzania, plus landlocked Uganda and Zambia, pooled their resources to establish a collective enterprise, the Eastern Africa National Shipping Line. Lacking the necessary technical expertise and financial capital to enter the sector, they went into partnership with Southern Lines, a firm owned by white entrepreneurs with tight connections in the business world of the Kenyan port of Mombasa. The partner states launched the EANSL in 1966. Its first cargo vessel, the MV Harambee, was inaugurated the following year.

This shipping world was a complicated place. It drew together a wide cast of individuals, organisations, and businesses with overlapping and conflicting interests. Tracing this history requires moving across geographic sites, from the noise of the port itself to air-conditioned boardrooms, government offices and conference halls. In Mombasa and Dar es Salaam, authorities inherited the challenge faced by their colonial era predecessor in stabilising and disciplining dockside workforces. Meanwhile, shipping agencies dominated by white Europeans continued to act as powerful mediators between local import-export firms and private enterprises overseas. In foreign capitals, cartel-style conferences which had formed the backbone of colonial shipping systems met to fix prices and drive out independent competitors, fuelling grievances in Eastern Africa. These relationships were marked by not just tensions between states and businesses, but contoured by the politics of race (it might be added that shipping was an almost exclusively male world).

From its inception, the EANSL was riven by tensions. These arose from distrust among the four member states and especially with Southern Lines, whose presence rubbed up uneasily against the priority of ‘Africanising’ the region’s economies. In 1974, amid poisonous rancour among the parties, the four governments bought out Southern’s share in EANSL. But even then, breaking free of the status quo proved impossible. Paradoxically, despite being envisaged as a mechanism for economic decolonisation, the EANSL was the sole African member of the London-based Europe-East Africa Conference. The Conference was the object of ire for slapping surcharges on the ports of Dar es Salaam and Mombasa when they became congested – costs that were inevitably borne by East African importers and exporters. But there seemed little opportunity to operate outside of the Conference, which squeezed out external competition through its pricing strategies.

Global economic turbulence also inhibited East African attempts to remake the economic geography of the region’s shipping sector. In the aftermath of the 1973 oil shock, the region’s crisis-hit governments sought to develop its export markets in the nouveau riche Arab petrostates. But they found their own limited shipping infrastructure constrained this pivot. While the oil producers of the Middle East showed, via the nationalisation of their hydrocarbon resources, how post-colonial states could decisively bolster their sovereignty, the travails of EANSL reflected the challenges in breaking with the ‘invisible’ ties of dependency. Amid economic crisis and geopolitical confrontation, the regional East African Community collapsed in 1977. The EANSL struggled on until 1980, when its financial situation had deteriorated beyond repair and the four owners lacked the political inclination to prop it up further still.

The EANSL was ultimately a failed enterprise. But for a period in which the absence of accessible archives on global shipping companies reflects the opaque nature of the sector, documents about the EANSL held at the Kenya National Archives in Nairobi offer unparalleled insights into the post-colonial politics of shipping. This research, generously funded by the Economic History Society through a Carnevali Small Research Grant, will investigate these connections, to shed light on processes of global economic integration and dependency from the perspectives of the Third World.

To contact the author:

George Roberts

@g_m_roberts

University of Sheffield