Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures

by Beverly Lemire (University of Alberta)

The Society has arranged with CUP that a 20% discount is available on this book, valid until the 11th October 2018. The discount page is: www.cambridge.org/ehs20

Our ancestors knew the comfort of a pipe. But some may have preferred the functionality of cigarettes, an alternative to the rituals of nursing tobacco embers. Historic periods are defined by habits and fashions, manifesting economic and political systems, legal and illegal. These are the focus of my recent book. New networks of exchange, cross-cultural contact and material translation defined the period c. 1500-1820. Tobacco is one thematic focus. I trace how global societies domesticated a Native American herb and Native American forms of tobacco. Its spread distinguishes this period from all others, when the Americas were fully integrated into global systems. Native American knowledge, lands and communities then faced determined intervention from all quarters. This crop became commoditized within decades, eluding censure to become an essential component of sociability, whether in Japan or Southeast Asia, the West Coast of Africa or the courts of Europe. [Figure 1]

Tobacco is a denominator of the early global era, grown in almost every context by 1600 and incorporated into diverse cultural and material modes. Importantly, its capacity to ease fatigue was quickly noted by military and imperial administrations and soon used to discipline or encourage essential labour. A sacred herb was transposed into a worldly good. Modes of coercive consumption were notable in the western slave trade, as well as on plantations. Tobacco also served disciplinary roles among workers essential to the movement of cargoes; deep-sea long-distance sailors and riverine paddlers in the North American fur trade were vulnerable to exploitation on account of their need and dependence on tobacco during long stints of back-breaking labour.

Early global trade built on established commercial patterns – most importantly the textile trade including the long-standing exchange of fabric for fur. The fabric / fur dynamic linked northern and southern Eurasia and north Africa, a pattern of elite and non-elite consumption that surged after the late 1500s, especially with the establishment of the Qing dynasty in China (1636-1912), with their deep cultural preference for furs. Equally important, deepening trade on the northeast coast of North America formalized Indigenous Americans’ appetite for cloth, willingly bartered for furs. The fabric / fur exchange preceded and continued with western colonization in the Americas. Meanwhile, on both sides of the Bering Strait and along the northwest coast of America, Indigenous communities were pulled more fully into the Qing economic orbit, with its boundless demand for peltry. Russian imperial expansion also served this commerce. The ecologies touched by this capacious trade extended worldwide, memorialized in surviving Qing fur garments and secondhand beaver hats traded for slaves in West Africa.

I routinely incorporate object study in my analysis, an essential way to assess the dynamism of consumer practice. I trawled museum collections as commonly as archives and libraries, where I found essential evidence of globalized fads and fashions. Strategies of a Qing-era man are revealed, as he navigated Chinese sumptuary laws while attempting to demonstrate fashion (on a budget). His seeming mink-lined robe used this costly fur only where it was visible. Sheepskin lined all the hidden areas. His concern for thrift is laid bare, along with his love of style.

Elsewhere in the book, I trace responses to early globalism through translations and interpretations of early global Asian designs, in needlework. The movement of people, as well as vast cargoes, stimulated these expressive fashions, ones that required minimal investment and gave voice to the widest range of women and men. The flow of Asian patterned goods and (often forced) relocation of Asian embroiderers to Europe began this tale – both increased the clamour for floral-patterned wares. This analysis culminates in North America with the turn from geometric to floral patterning among Indigenous embroiderers. They, too, responded to the influx of Asian floriated things. Europeans were intermediaries in this stage of the global process.

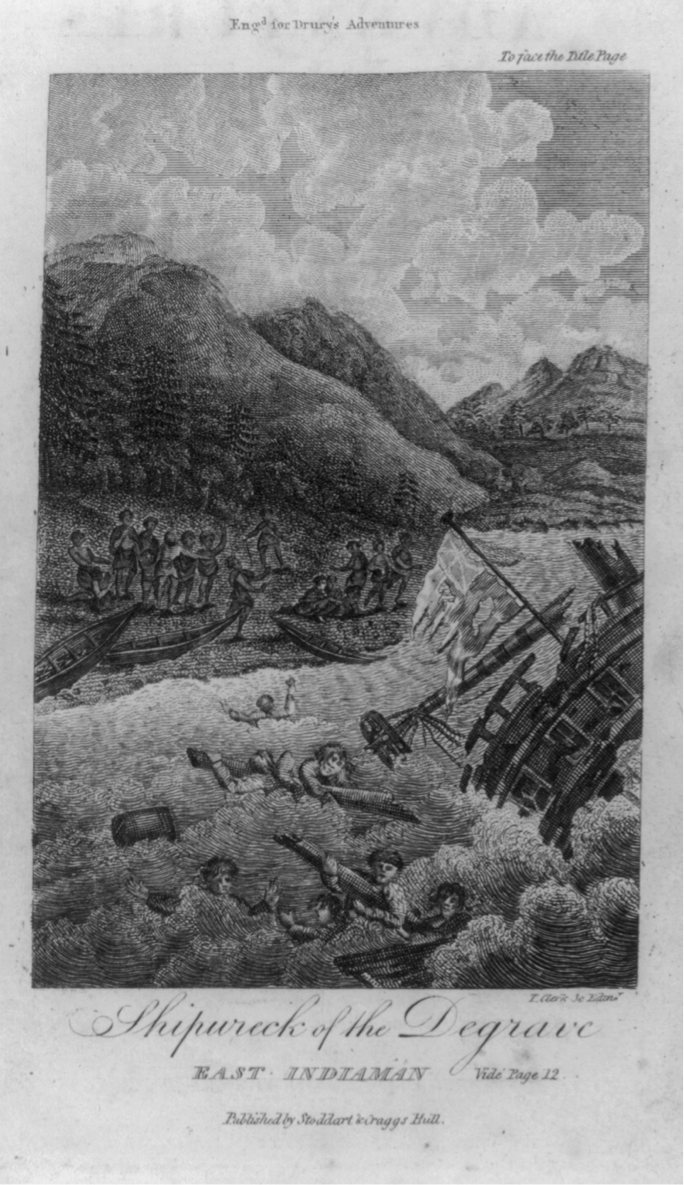

Human desires and shifting tastes are recurring themes, expressed in efforts to acquire new goods through various entrepreneurial channels. ‘Industriousness’ was manifest by women of many ethnicities through petty market-oriented trade, as well as waged employment, often working at the margins of formal commerce. Industriousness, legal and extralegal, large and small, flourished in conjunction with large-scale enterprise. Extralegal activities irritated administrators, however, who wanted only regulated and measurable business. Nonetheless, extralegal activities were ubiquitous in every imperial realm and an important vein of entrepreneurship. My case studies in extralegal ventures range from the traffic in tropical shells in Kirkcudbright, Scotland; the lucrative smuggling of European wool cloth to Qing China, a new mode among urban cognoscenti; and the harvesting of peppercorns from a Kentish beach, illustrating the importance of shipwrecks in redistributing cargoes to coastal communities everywhere. [Figure 2] Coastal peoples were schooled in the materials of globalism, cast up by the tides, though some authorities might call them criminal. Ultimately, the shifting materials of daily life marked this dynamic history.

To contact the author: Lemire@ualberta.ca