How JP Morgan Picked Winners and Losers in the Panic of 1907: The Importance of Individuals over Institutions

by Jon Moen (University of Mississippi) & Mary Rodgers (SUNY, Oswego).

This blog is part of our EHS 2020 Annual Conference Blog Series.

We study J. P. Morgan’s decision making during the Panic of 1907 and find insights for understanding the outcomes of current financial crises. Morgan relied as much on his personal experience as on formal institutions like the New York Clearing House, when deciding how to combat the Panic. Our main conclusion is that lenders may rely on their past experience during a crisis rather than on institutional and legal arrangements in formulating a response to a financial crisis. The existence of sophisticated and powerful institutions like the Bank of England or the Federal Reserve System may not guarantee optimal policy responses if leaders make their decisions on the basis of personal experience rather than well-established guidelines. This will result in decisions yielding sub-par outcomes for society compared to those made if formal procedures and data-based decisions had been proffered.

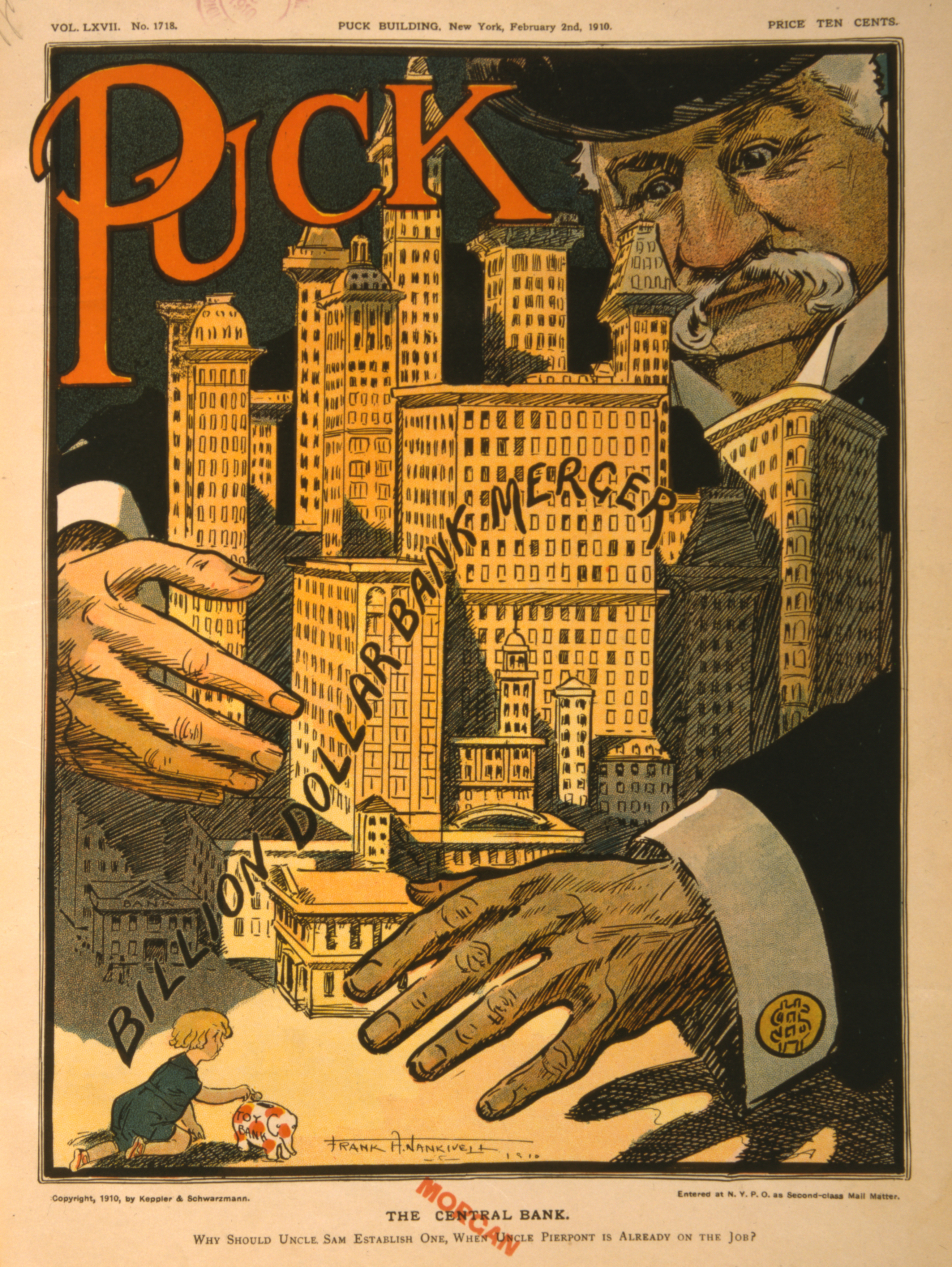

Morgan’s influence in arresting the Panic of 1907 is widely acknowledged. In the absence of a formal lender of last resort in the United States, he personally determined which financial institutions to save and which to let fail in New York. Morgan had two sources of information about the distressed firms: (1) analysis done by six committees of financial experts he assigned to estimate firms’ solvency and (2) decades of personal experience working with those same institutions and their leaders in his investment banking underwriting syndicates. Morgan’s decisions to provide or withhold aid to the teetering institutions appears to track more closely with his prior syndicate experience with each banker, rather than with the recommendations made by committees’ analysis of available data. Crucially, he chose to let the Knickerbocker Trust fail despite one committee’s estimate it was solvent and another’s that it had too little time to make a strong recommendation. Morgan had had a very bad business experience with the Knickerbocker and its president, Charles Barney, but he had had positive experiences with all the other firms requesting aid. Had the Knickerbocker been aided, the panic might have been avoided all together.

The lesson we draw for present day policy is that the individuals responsible for crisis resolution will bring to the table policies based on personal experience that will influence the crisis resolution in ways that may not have been expected a priori. Their policies might not be consistent with the general well-being of the financial markets involved, as may have been the case with Morgan letting Knickerbocker fail. A recent example that echoes the experience of Morgan in 1907 can be seen in the leadership of Ben Bernanke, Timothy Geithner and Henry Paulson during the financial crisis in 2008. They had a formal lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve System, to guide them in responding to the crisis in 2008. While they may have had the well-being of financial markets more in the forefront of their decision making from the start, controversy still surrounds the failure of Lehman Brothers and the lack of support to provide them with a lifeline from the Federal Reserve. The latter could have provided aid, and this reveals that the individuals making the decisions, and not the mere existence of a lender of last resort institution and the analysis such an institution will muster, can greatly affect the course of a financial crisis. Reliance on personal experience at the expense of institutional arrangements is clearly not limited only to the responses made to financial crises. The coronavirus epidemic is one such example worth examining with this framework.

Jon Moen – jmoen@olemiss.edu