How well off were the occupants of early modern almshouses?

by Angela Nicholls (University of Warwick).

Almhouses in Early Modern England is published by Boydell Press. SAVE 25% when you order direct from the publisher – offer ends on the 13th December 2018. See below for details.

Almshouses, charitable foundations providing accommodation for poor people, are a feature of many towns and villages. Some are very old, with their roots in medieval England as monastic infirmaries for the sick, pilgrims and travellers, or as chantries offering prayers for the souls of their benefactors. Many survived the Reformation to be joined by a remarkable number of new foundations between around 1560 and 1730. For many of them their principal purpose was as sites of memorialisation and display, tangible representations of the philanthropy of their wealthy donors. But they are also some of the few examples of poor people’s housing to have survived from the early modern period, so can they tell us anything about the material lives of the people who lived in them?

Paul Slack famously referred to almspeople as ‘respectable, gowned Trollopian worthies’, and there are many examples to justify that view, for instance Holy Cross Hospital, Winchester, refounded in 1445 as the House of Noble Poverty. But these are not typical. Nevertheless, many early modern almshouse buildings are instantly recognisable, with the ubiquitous row of chimneys often the first indication of the identity of the building.

Individual chimneys and, often, separate front doors are evidence of private domestic space, far removed from the communal halls of the earlier medieval period, or the institutional dormitories of the nineteenth century workhouses which came later. Accommodating almspeople in their own rooms was not just a reflection of general changes in domestic architecture at the time, which placed greater emphasis on comfort and privacy, but represented a change in how almspeople were viewed and how they were expected to live their lives. Instead of living communally with meals provided, in the majority of post-Reformation almshouses the residents would have lived independently, buying their own food, cooking it themselves on their own hearth and eating it by themselves in their rooms. The importance of the hearth was not only as the practical means of heating and cooking, but was central to questions of identity and social status. Together with individual front doors, these features gave occupants a degree of independence and autonomy; they enabled almspeople to live independently despite their economic dependence, and to adopt the appearance if not the reality of independent householders.

The retreat from communal living also meant that almspeople had to support themselves rather than have all their needs met by the almshouse. This was achieved in many places by a transition to monetary allowances or stipends with which almspeople could purchase their own food and necessities, but the existence and level of these stipends varied considerably. Late medieval almshouses often specified an allowance of a penny a day, which would have provided a basic but adequate living in the fifteenth century, but was seriously eroded by sixteenth-century inflation. Thus when Lawrence Sheriff, a London mercer, established in 1567 an almshouse for four poor men in his home town of Rugby, his will gave each of them the traditional penny a day, or £1 10s 4d a year. Yet with inflation, if these stipends were to match the real value of their late-fifteenth-century counterparts, his almsmen would actually have needed £4 5s 5d a year.[1]

The nationwide system of poor relief established by the Tudor Poor Laws, and the survival of poor relief accounts from many parishes by the late seventeenth century, provide an opportunity to see the actual amounts disbursed in relief by overseers of the poor to parish paupers. From the level of payments made to elderly paupers no longer capable of work it is possible to calculate the barest minimum which an elderly person living rent free in an almshouse might have needed to feed and clothe themself and keep warm.[2] Such a subsistence level in the 1690s equates to an annual sum of £3 17s which can be adjusted for inflation and used to compare with a range of known almshouse stipends from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

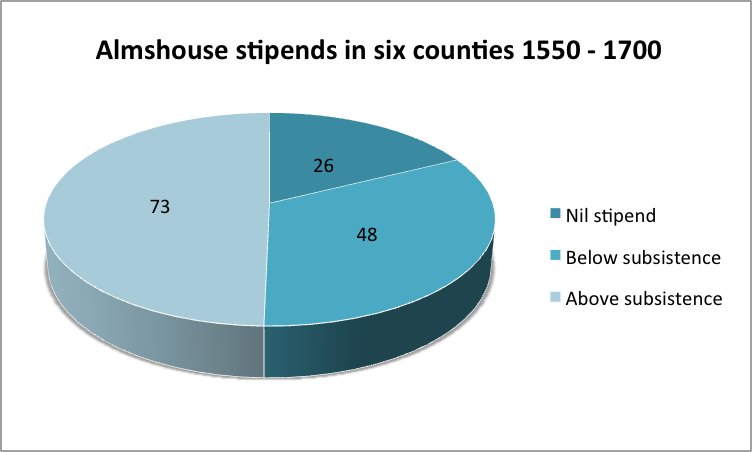

The results of this comparison are interesting, even surprising. Using data from 147 known almshouse stipends in six different counties (Durham, Yorkshire, Norfolk, Warwickshire, Buckinghamshire and Kent) it seems that less than half of early modern almshouses provided their occupants with stipends which were sufficient to live on. Many provided no financial assistance at all.

The inescapable conclusion is that the benefits provided to early modern almspeople were in many cases only a contribution towards their subsistence. In this respect almshouse occupants were no different from the recipients of parish poor relief, who rarely had their living costs met in full.

Yet, even in one of the poorer establishments, almshouse residents had distinct advantages over other poor people. Principally these were the security of their accommodation, the permanence and regularity of any financial allowance, no matter how small, and the autonomy this gave them. Almshouse residents may also have had an enhanced status as ‘approved’, deserving poor. The location of many almshouses, beside the church, in the high street, or next to the guildhall, seems to have been purposely designed to solicit alms from passers-by, at a time when begging was officially discouraged.

SAVE 25% when you order direct from the publisher. Discount applies to print and eBook editions. Click the link, add to basket and enter offer code BB500 in the box at the checkout. Alternatively call Boydell’s distributor, Wiley, on 01243 843 291 and quote the same code. Offer ends one month after the date of upload. Any queries please email marketing@boydell.co.uk

NOTES

[1] Inflation index derived from H. Phelps Brown and S. V. Hopkins, A Perspective of Wages and Prices (London and New York, 1981) pp. 13-59.

[2] L. A. Botelho, Old Age and the English Poor Law, 1500 – 1700 (Woodbridge, 2004) pp. 147-8.