Land reform and agrarian conflict in 1930s Spain

Jordi Domènech (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) and Francisco Herreros (Institute of Policies and Public Goods, Spanish Higher Scientific Council)

Government intervention in land markets is always fraught with potential problems. Intervention generates clearly demarcated groups of winners and losers as land is the main asset owned by households in predominantly agrarian contexts. Consequently, intervention can lead to large, generally welfare-reducing changes in the behaviour of the main groups affected by reform, and to policies being poorly targeted towards potential beneficiaries.

In this paper (available here), we analyse the impact of tenancy reform in the early 1930s on Spanish land markets. Adapting general laws to local and regional variation in land tenure patterns and heterogeneity in rural contracts was one of the problems of agricultural policies in 1930s Spain. In the case of Catalonia in the 1930s, the interest of the case lies in the adaptation of a centralized tenancy reform, aimed at fixed-rent contracts, to sharecropping contracts that were predominant in Catalan agriculture. This was more typically the case of sharecropping contracts on vineyards, the case of customary sharecropping contract (rabassa morta), subject to various legal changes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It is considered that the 1930s culminated a period of conflicts between the so called rabassaires (sharecroppers under rabassa morta contracts) and owners of land.

The divisions between owners of land and tenants was one of the central cleavages of Catalonia in the 20th century. This was so even in an area that had seen substantial industrialization. In the early 1920s, work started on a Catalan law of rural contracts, aimed especially at sharecroppers. A law, passed on the 21st March 1934, allowed the re-negotiation of existing rural contracts and prohibited the eviction of tenants who had been less than 6 years under the same contract. More importantly, it opened the door to forced sales of land to long-term tenants. Such legislative changes posed a threat to the status quo and the Spanish Constitutional Court ruled the law was unconstitutional.

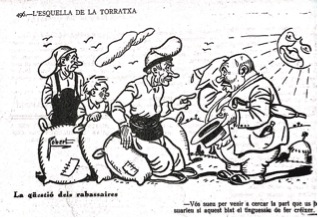

The comparative literature on the impacts of land reforms argues that land reform, in this case tenancy reform, can in fact change agrarian structures. When property rights are threatened, landowners react by selling land or interrupting existing tenancy contracts, mechanizing and hiring labourers. Agrarian structure is therefore endogenous to existing threats to property rights. The extent of insecurity in property rights in 1930s Catalonia can be seen in the wave of litigation over sharecropping contracts. Over 30,000 contracts were revised in the courts in late 1931 and 1932 which provoked satirical cartoons (Figure 01).

Translation: The rabaissaire question: Peasant: You sweat by coming here to claim your part of the harvest, you would be sweating more if you were to grow it by yourself.

The first wave of petitions to revise contracts led overwhelmingly to most petitions being nullified by the courts. This was most pronounced in the Spanish Supreme Court which ruled against the sharecropper in most of the around 30,000 petitions of contract revision. Nonetheless, sharecroppers were protected by the Catalan autonomous government. The political context in which the Catalan government operated became even more charged in October 1934. That month, with signs that the Centre-Right government was moving towards more reactionary positions, the Generalitat participated in a rebellion orchestrated by the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and Left Republicans. It is in this context of suspension of civil liberties that landowners now had a freer hand to evict unruly peasants. The fact that some sharecroppers did not surrender their harvest meant they could be evicted straight away according to the new rules set by the new military governor of Catalonia.

We use the number of cases of completed and initiated tenant evictions from October 1934 to around mid -1935 as the main dependent variable in the paper. Data were collected from a report produced by the main Catalan tenant union, Unió de Rabassaires (Rabassaires’ Union), published in late 1935 to publicize and denounce tenant evictions or attempts of evicting tenants.

Combining the spatial analysis of eviction cases with individual information on evictors and evicted, we can be reasonably confident about several facts around evictions and terminated contracts in 1930s Catalonia. Our data show that that rabassa morta legacies were not the main determinant of evictions. About 6 per cent of terminated contracts were open ended rabassa morta contracts (arbitrarily set at 150 years in the graph). About 12 per cent of evictions were linked to contracts longer than 50 years, which were probably oral contracts (since Spanish legislation had given a maximum of 50 years). Figure 2 gives the contracts lengths of terminated and threatened contracts.

The spatial distribution of evictions is also consistent with the lack of historical legacies of conflict. Evictions were not more common in historical rabassa morta areas, nor were they typical of areas with a larger share of land planted with vines.

Our study provides a substantial revision of claims by unions or historians about very high levels of conflict in the Catalan countryside during the Second Republic. In many cases, there had a long process of adaptation and fine-tuning of contractual forms to crops and soil and climatic conditions which increased the costs of altering existing institutional arrangements.

To contact the authors: