Loans of the Revolution: How Mexico Borrowed as the State Collapsed in 1912–13

by Leonardo Weller (São Paulo School of Economics – FGV)

Read the full article on The Economic History Review – published in Augus 2018, available here

Mexico borrowed £6 million abroad in 1913, amidst a civil war that destroyed the state and killed over two million people. Civil wars tend to make creditors wary because of their inevitable consequences: if the borrowing government wins, it will need to spend on reconstruction, leaving it short of cash to pay their debt back; in case of defeat, the new incoming government is bound to repudiate its enemy’s debt. The Mexican loan of 1913 is unusual because the bankers in charge knew that the government was likely to lose or, at best, fight a long and bloody war. Paribas, the head of the syndicate that underwrote the loan, received first-hand reports from an agent in Mexico City, according to whom:

‘The political situation is (. . .) obscure because the country is still infested by rebellious bands while General Huerta is only president of the republic in a provisory character (…), and no one knows how that will end’.

Victoriano Huerta assassinated Francisco Madero, leader of the revolution who deposed the long-serving autocrat Porfirio Díaz who was in office at various times between the 1870s and 1911. The report from the Mexican agent was accurate: Huerta aimed to re-established Díaz’s stable regime, but his counter-revolution fostered an unlikely but powerful alliance between popular insurgents such as Emiliano Zapata and moderate politicians linked to Madero. Pressured by the financial toll of the war, the Huerta administration defaulted on its entire debt – including the loan take out 1913 – in 1914. The insurgents took Mexico City and deposed the dictator, but the war continued and Mexico became a failed state. Peace only came in 1917, but the government in charge of reconstructing the country did not pay the sovereign debt.

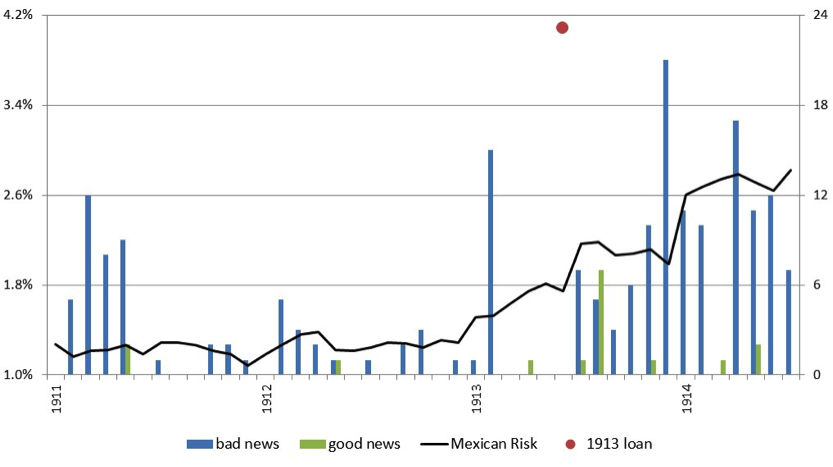

Paribas and its fellow syndicate members underwrote the 1913 loan at rather poor borrowing conditions: 6 per cent interest, 90 per cent discount, and 10 years maturity, which result in a 4 per cent risk premium (a measure of credit cost), twice higher than the premium applied to the Mexican debt already floating on the London Stock Exchange at the time. In plain language, the loan was remarkably expensive vis-à-vis market conditions. This discrepancy appears in the graph below: The solid line is the premium at which the secondary market traded old Mexican bonds, and the dot is the premium at which the banks issued the new loan in 1913.

Table 01. Mexican risk and reports in The Times in Mexico.

The bankers themselves considered the loan as ‘too severe a burden on the Government’, but agreed that the operation had to be arranged ‘in our favour’ because of the ‘terrible political circumstances’ in the country. In line with this dire assessment of Mexican political conditions, Paribas sold its entire share of the 1913 loan. In fact, Paribas acted solely as an underwriter to float the bonds on the international market, as opposed to underwriter and final creditor (holding a share of the bonds). The bank also liquidated all its other Mexican assets it held, including a significant share of the Banco Nacional de México. A conflict of interest explains why Paribas underwrote the 1913 loan: The new credit created confidence among the public and sustained the price of all Mexican securities, which enabled Paribas to eliminate its exposure to Mexico without realising losses. The liquidation was profitable overall: in particular, the bank sold the 1913 bonds at a 6 per cent margin.

Undoubtedly, Paribas’ gains were at the expense of others. Why, then, did bondholders agree to purchase the debt? Figure 1 suggests (and econometric tests confirm) that positive press reports influenced the market. The Times published negative news on Mexico when the revolutionaries deposed Díaz and the counter-revolutionaries assassinated Madero, in 1911 and 1913, respectively, but it subsequently altered its editorial stance by publishing good news and generally remaining going quiet on the country. Meanwhile, bondholders continued buying Mexican bonds in spite of the civil war and, as a result, Mexican risk stayed below 2 per cent, a relatively low rate.

The public read over-optimistic news, while the bankers had access to pessimistic but accurate reports from their agents in Mexico. Thus, Paribas benefited from asymmetric information, which explains why it could profit at the expenses of the final creditors.

This case study is at odds with the most recent historical literature on sovereign debt, which stresses the role of debt underwriters as gatekeepers, responsible for guiding the market. The literature asserts that bankers produced signals that separated the trustworthy borrowers from the rest. In contrast, Paribas exploited the market´s disinformation to profit from the liquidation of its Mexican businesses.

To contact the author:

@leoweller