Militantism and Non-Violence in the Women’s Suffrage Movement

This blog presents an overview of Valeria Rueda at the University of Nottingham’s project, “Militantism and Non Violence in the Women’s Suffrage Movement”, which has recently been awarded a Carnevali Small Research grant by the Economic History Society.

—

From the discord between suffragists and suffragettes, to the schism within the American Civil Rights Movement between the non-violence of the NAACP and the militancy of “Black Power”, activist groups throughout history have split over the means to achieve social change. Yet, there is little quantitative evidence comparing these tactics. This project will fill this gap by drawing inferences from the history of the women’s suffrage movement in Britain. In doing so, we will also push the frontier in the historical understanding of how the campaign for women’s suffrage won public opinion. Specifically, this project will compare the effectiveness of militant versus non-violent tactics in the British movement for women’s suffrage in the period of 1910-1914. We will assess success in terms of the spread of activism and the influence on public opinion.

Two societies led the movement for women’s suffrage in Britain, with opposing tactics. On the one hand, the suffragists in the National Union for Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the largest and oldest suffragist society advocated for peaceful, “non-militant” and “constitutional” tactics. Their goal was to convince Parliament to enfranchise women through institutional channels such as petitioning and lobbying. On the other hand, the suffragettes in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) became known worldwide for their pioneering militant tactics that did not shy away from disrupting public order and damaging private property.

We aim to compare the efficacy of militant tactics to that of constitutionalists in their effectiveness in politically socializing citizens. To achieve this aim, we will collect information on all the meetings and events organized by these societies in the period 1910-1914. This will allow us to shed light on their distribution, their evolution over time, and their consequences on a variety of outcomes.

The empirical historical political economy literature has made tremendous progress in understanding how activists developed a coalition of politicians supporting women’s suffrage (Wingerden, 1999; Teele, 2018), and their role in the political activation of female voters (Carpenter et al, 2018; Morgan-Collins and Natusch, 2022; Morgan-Collins and Rueda, 2023). Less is known quantitatively about how they shaped public opinion. Qualitatively, social historians have debated this issue. For instance, Pugh (2000) argues that militantism hurt the cause. Mayhall (2023) emphasizes the diversity of attitudes towards lawbreaking within the militant movement. The violence of the police repression in response to militant acts, with multiple allegations of sexual assault, may have also increased sympathy for the suffragettes.

Through the systematic gathering and quantitative analysis of historical records, this project will be the first quantitative contribution to this debate. We have set three specific objectives.

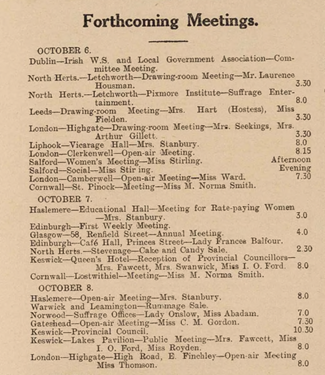

Our first objective is to create a comprehensive database of meetings organized by suffrage societies. We will establish a map and a timeline of events organized by women’s suffrage organizations. To do so, we will digitize previously untapped records from the weekly publications of these organizations. These newspapers, published every week, systematically listed the location, date, and name of the organiser for their forthcoming events nationally.

The second objective is descriptive. With the map and timeline of meetings, we will analyse the reach of the movements. We will be able to answer the following previously unstudied questions: Which of the two groups had the organizational capacity to gather more frequent meetings? Which one had a wider geographical reach? Which one targeted people on a broader socioeconomic spectrum? Were the two movements complementary or substitutes for one another?

The third objective is analytical. We will determine how effective these events were at increasing the salience of women’s issues and at politically activating women. We will measure the prominence and duration of news coverage of women’s issues after events, using text analysis tools and local newspaper records. We will first establish which meetings led to more social unrest. This first step will permit verifying whether WSPU events were more disruptive. We will then check how they affected public opinion by analysing the coverage of women’s issues in the long run.

We will keep the EHS updated on the results of this project through another blog post!

To contact the author:

Valeria Rueda

valeria.rueda@nottingham.ac.uk

University of Nottingham and CEPR Research Affiliate