Plague and long-term development

by Guido Alfani (Bocconi University, Dondena Centre and IGIER)

The full paper has been published in The Economic History Review and is available here.

A YouTube video accompanies this work and can be found here.

How did preindustrial economies react to extreme mortality crises caused by severe epidemics of plague? Were health shocks of this kind able to shape long-term development patterns? While past research focused on the Black Death that affected Europe during 1347-52 ( Álvarez Nogal and Prados de la Escosura 2013; Clark 2007; Voigtländer and Voth 2013), in a forthcoming article with Marco Percoco we analyse the long-term consequences of what was by far the worst mortality crisis affecting Italy during the Early Modern period: the 1629-30 plague which killed an estimated 30-35% of the northern Italian population — about two million victims.

Figure 1 Luigi Pellegrini Scaramuccia (1670), Federico Borromeo visits the plague ward during the 1630 plague,

Source: Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana

This episode is significant in Italian history, and more generally, for our understanding of the Little Divergence between the North and South of Europe. It had recently been hypothesized that the 1630 plague was the source of Italy’s relative decline during the seventeenth century (Alfani 2013). However, this hypothesis lacked solid empirical evidence. To resolve this question, we take a different approach from previous studies, and demonstrate that plague lowered the trajectory of development of Italian cities. We argue that this was mostly due to a productivity shock caused by the plague, but we also explore other contributing factors. Consequently, we provide support for the view that the economic consequences of severe demographic shocks need to be understood and studied on a case-by-case basis, as the historical context in which they occurred can lead to very different outcomes (Alfani and Murphy 2017).

After assembling a new database of mortality rates in a sample of 56 cities, we estimate a model of population growth allowing for different regimes of growth. We build on the seminal papers by Davis and Weinstein (2002), and Brakman et al. (2004) who based their analysis on a new framework in economic geography framework in which a relative city size growth model is estimated to determine whether a shock has temporary or persistent effects. We find that cities affected by the 1629-30 plague experienced persistent, long-term effects (i.e., up to 1800) on their pattern of relative population growth.

Figure 2. Giacomo Borlone de Buschis (attributed), Triumph of Death (1485), fresco

Source: Oratorio dei Disciplini, Clusone (Italy).

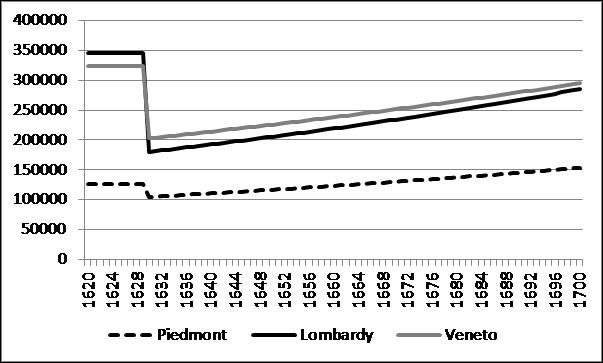

We complete our analysis by estimating the absolute impact of the epidemic. We find that in northern Italian regions the plague caused a lasting decline in both the size and rate of change of urban populations. The lasting damage done to the urban population are shown in Figure 3. For urbanization rates it will suffice to notice that across the North of Italy, by 1700 (70 years after the 1630 plague), they were still more than 20 per cent lower than in the decades preceding the catastrophe (16.1 per cent in 1700 versus an estimated 20.4 per cent in 1600, for cities >5,000). Overall, these findings suggest that surges in plagues may contribute to the decline of economic regions or whole countries. Our conclusions are strengthened by showing that while there is clear evidence of the negative consequences of the 1630 plague, there is hardly any evidence for a positive effect (Pamuk 2007). We hypothesize that the potential positive consequences of the 1630 plague were entirely eroded by a negative productivity shock.

Figure 3. Size of the urban population in Piedmont, Lombardy, and Veneto (1620-1700)

Source: see original article

Demonstrating that the plague had a persistent negative effect on many key Italian urban economies, we provide support for the hypothesis that the origins of relative economic decline in northern Italy are to be found in particularly unfavorable epidemiological conditions. It was the context in which an epidemic occurred that increased its ability to affect the economy, not the plague itself. Indeed, the 1630 plague affected the main states of the Italian Peninsula at the worst possible moment when its manufacturing were dealing with increasing competition from northern European countries. This explanation, however, provides a different interpretation to the Little Divergence in recent literature.

To contact the author: guido.alfani@unibocconi.it

References

Alfani, G., ‘Plague in seventeenth century Europe and the decline of Italy: and epidemiological hypothesis’, European Review of Economic History, 17, 4 (2013), pp. 408-430

Alfani, G. and Murphy, T., ‘Plague and Lethal Epidemics in the Pre-Industrial World’, Journal of Economic History, 77, 1 (2017), pp. 314-343.

Alfani, G. and Percoco, M., ‘Plague and long-term development: the lasting effects of the 1629-30 epidemic on the Italian cities’, The Economic History Review, forthcoming, https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12652

Álvarez Nogal, C. and Prados de la Escosura,L., ‘The Rise and Fall of Spain (1270-1850)’, Economic History Review, 66, 1 (2013), pp. 1–37.

Brakman, S., Garretsen H., Schramm M. ‘The Strategic Bombing of German Cities during World War II and its Impact on City Growth’, Journal of Economic Geography, 4 (2004), pp. 201-218.

Clark, G., A Farewell to Alms (Princeton, 2007).

Davis, D.R. and Weinstein, D.E. ‘Bones, Bombs, and Break Points: The Geography of Economic Activity’, American Economic Review, 92, 5 (2002), pp. 1269-1289.

Pamuk, S., ‘The Black Death and the origins of the ‘Great Divergence’ across Europe, 1300-1600’, European Review of Economic History, 11 (2007), pp. 289-317.

Voigtländer, N. and H.J. Voth, ‘The Three Horsemen of Riches: Plague, War, and Urbanization in Early Modern Europe’, Review of Economic Studies 80, 2 (2013), pp. 774–811.