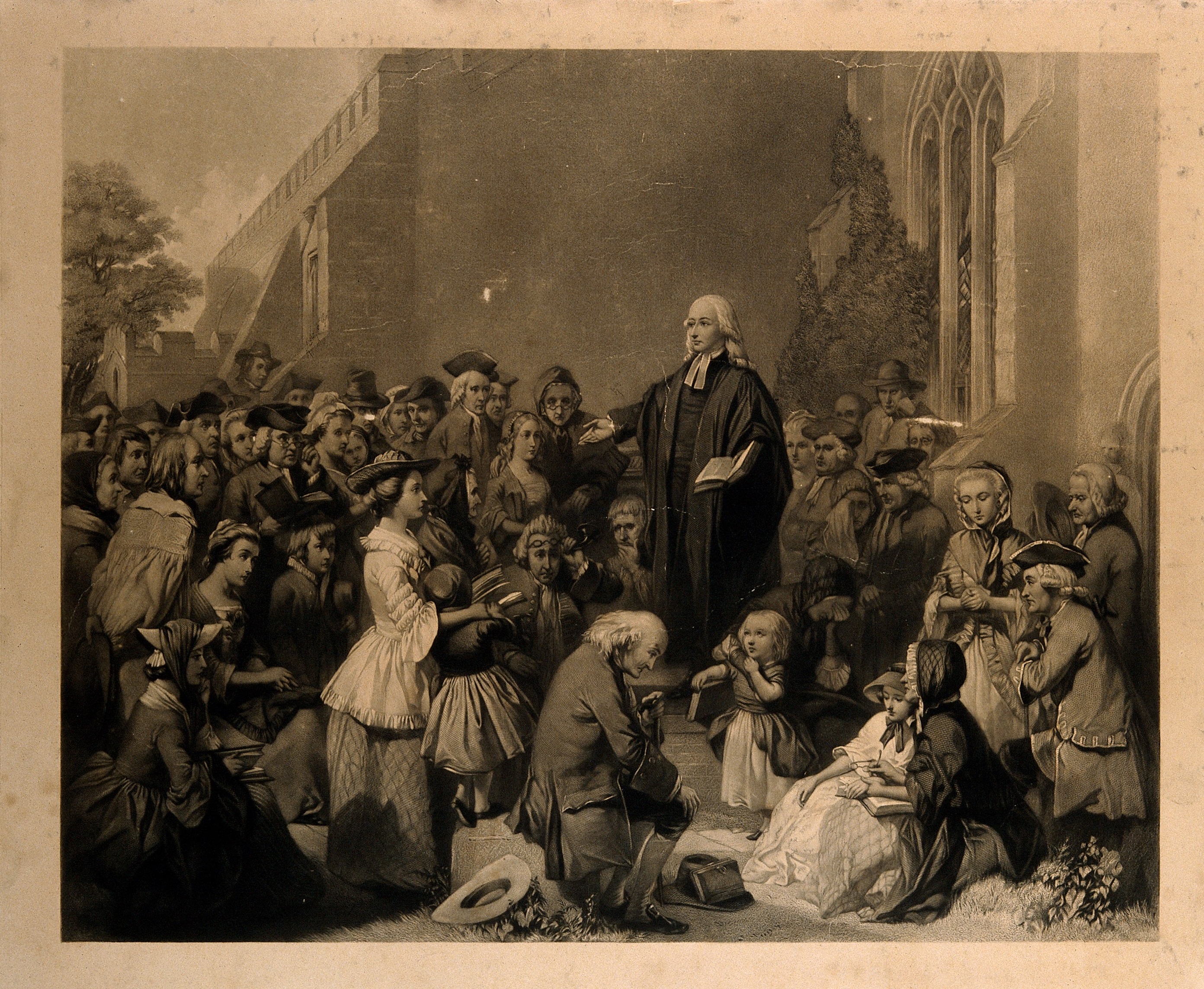

Religion and economics: early Methodism was underpinned by sophisticated financial management

by Clive Norris (Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, Oxford Brookes University)

John Wesley’s efforts to spread the Gospel throughout the British Isles and beyond in the later eighteenth century relied on resources generated and managed using a wide range of techniques. This study of contemporary financial records shows that the evangelistic energy and fervour of Methodist preachers and members was supported – but also frequently constrained – by the movement’s approach to financial management.

The central priority of Wesley’s movement or ‘Connexion’ was to supply enough preachers to meet the needs of the membership and attract new converts. Members’ dues provided the core financing for the growing cadre of travelling preachers, while tools such as central grants channelled resources from richer to poorer areas.

Although the increasing number of married preachers with children raised per capita costs, the annual preachers’ conference tried to keep the deployment of preachers within the envelope of the resources available. By 1800, preaching costs probably exceeded £40,000 a year, met by around 110,000 members.

A second preoccupation was the capital and revenue funding of the expanding network of Wesleyan chapels, which numbered almost one thousand by 1800, costing perhaps £9,000 in annual debt interest alone.

From the 1760s, increasing use was made of an essentially commercial model, overseen by a central committee of business advisers. The opportunity to provide loans at attractive interest rates was offered to wealthier members and supporters, and these both financed chapel construction and offered a good home for their surplus funds. Interest costs were met by renting out seats in chapel, though some seats were always made available free to the poor.

Proposals for new chapels were reviewed annually by the Wesleyan conference, and although many were built without its approval, the resulting pressure on the movement’s finances became marked only after 1800. Chapels also enabled the Connexion to draw income from non-members, who typically outnumbered members by three to one in congregations.

Third, Wesleyan Methodists sought to spread the Gospel through the publication and distribution of cheap and readable publications, including Charles Wesley’s hymnals.

From the 1750s, the so-called Book Room became increasingly profitable, largely because by 1780, almost every aspect of production and distribution had been brought in-house. In particular, Wesleyan preachers were exhorted to market the publications to their members and congregations, and received 10% commission on sales. By 1800, the Book Room’s profits – typically £2,000 annually – were making a significant contribution to overall Connexional finances.

Fourth, the Connexion developed a portfolio of other activities, including educational services such as Sunday schools, poor relief programmes and overseas missions, especially in the West Indies. Most of these activities were not financed directly by the membership.

A key approach was to appeal for public subscriptions, which were widely used outside Methodism to fund public buildings and services such as hospitals, but there were many variations. In the West Indies, for example, some Wesleyan missionaries supplied spiritual services to slave-owners under contract.

One major result of these developments was that the Wesleyan Methodist movement became increasingly dependent on its richer members and supporters. For example, though its areas of greatest membership strength were Yorkshire and the South West of England, subscription income came disproportionately from wealthy London.

But until well into the nineteenth century, this seems not to have blunted its expansion: membership almost doubled between 1800 and 1820. Indeed, the complex and flexible financial policies and practices that underpinned the movement were crucially important in enabling it to respond to the spiritual and (to an extent) material needs of Britain’s growing and geographically shifting population.