Small Bills and Petty Finance: co-creating the history of the Old Poor Law

by Alannah Tomkins (Keele University)

Alannah Tomkins and Professor Tim Hitchcock (University of Sussex), won an AHRC award to investigate ‘Small Bills and Petty Finance: co-creating the history of the Old Poor Law’. It is a three-year project from January 2018. The application was for £728K, which has been raised, through indexing, to £740K. The project website can be found at: thepoorlaw.org.

Twice in my career I’ve been surprised by a brick – or more precisely by bricks, hurtling into my research agenda. In the first instance I found myself supervising a PhD student working on the historic use of brick as a building material in Staffordshire (from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries). The second time, the bricks snagged my interest independently.

The AHRC-funded project ‘Small bills and petty finance’ did not set out to look for bricks. Instead it promises to explore a little-used source for local history, the receipts and ‘vouchers’ gathered by parish authorities as they relieved or punished the poor, to write multiple biographies of the tradesmen and others who serviced the poor law. A parish workhouse, for example, exerted a considerable influence over a local economy when it routinely (and reliably) paid for foodstuffs, clothing, fuel and other necessaries. This influence or profit-motive has not been studied in any detail for the poor law before 1834, and vouchers’ innovative content is matched by an exciting methodology. The AHRC project calls on the time and expertise of archival volunteers to unfold and record the contents of thousands of vouchers surviving in the three target counties of Cumbria, East Sussex and Staffordshire. So where do the bricks come in?

The project started life in Staffordshire as a pilot in advance of AHRC funding. The volunteers met at the Stafford archives and started by calendaring the contents of vouchers for the market town of Uttoxeter, near the Staffordshire/Derbyshire border. And the Uttoxeter workhouse did not confine itself to accommodating and feeding the poor. Instead in the 1820s it managed two going concerns: a workhouse garden producing vegetables for use and sale, and a parish brickyard. Many parishes under the poor law embedded make-work schemes in their management of the resident poor, but no others that I’m aware of channelled pauper labour into the manufacture of bricks.

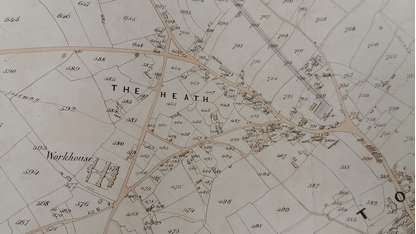

The workhouse and brickyard were located just to the north of the town of Uttoxeter, in an area known as The Heath. The land was subsequently used to build the Uttoxeter Union workhouse in 1837-8 (after the reform of the poor law in 1834) so no signs of the brickyard remain in the twenty-first century. It was, however, one of several such yards identified at The Heath in the tithe map for Uttoxeter of 1842, and probably made use of a fixed kiln rather than a temporary clamp. This can be deduced from the parish’s sale of both bricks and tiles to brickyard customers. Tiles were more refined products than bricks and require more control over the firing process, whereas clamp firings were more difficult to regulate. The yard provided periodic employment to the adult male poor of the Uttoxeter workhouse, in accordance with the seasonal pattern imposed on all brick manufacture at the time. Firings typically began in March or April each year, and continued until September or October depending on the weather.

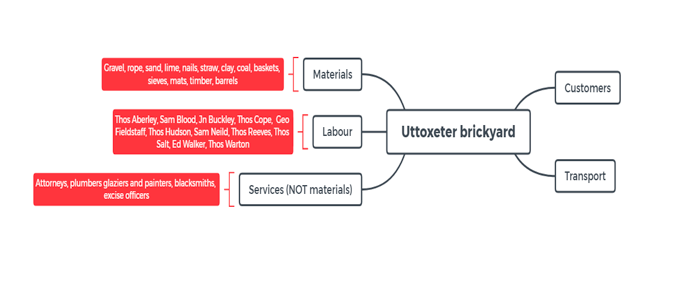

This is important because the variety of vouchers relating to the parish brickyard allow us to understand something of its place in the town’s economy, both as a producer and as a consumer of other products and services. Brickyards needed coal, so it is no surprise that one of the major expenses for the support of the yard lay in bringing coal to the town from elsewhere via the canal. The Uttoxeter canal wharf was also at The Heath, and access to transport by water may explain the development of a number of brickyards in its proximity. The yard also required wood and other raw materials in addition to clay, and specific products to protect the bricks after cutting but before firing. The parish bought quantities of archangel mats, rough woven pieces that could be used like a modern protective fleece to protect against frost damage. We are surmising that Uttoxeter used the mats to cover both the bricks and any tender plants in the workhouse garden.

Similarly the bricks were sold chiefly to local purchasers, including members of the parish vestry. Some men who were owed money by the parish for their work as suppliers allowed the debt to be offset by bricks. Finally the employment of workhouse men as brickyard labourers gives us, when combined with some genealogical research, a rare glimpse of the place of workhouse work in the life-cycle of the adult poor. More than one man employed at the yard in the 1820s and 1830s went on to independence as a lodging-house keeper in the town by the time of the 1841 census.

As I say, I’ve been surprised by brick. I had no idea that such a mundane product would prove so engaging. All this goes to show that it’s not the stolidity of the brick but its deployment that matters, historically speaking.

To contact the author: a.e.tomkins@keele.ac.uk