Taxation and Wealth Inequality in the German Territories of the Holy Roman Empire 1350-1800

by Victoria Gierok (Nuffield College, Oxford)

This blog is part of our EHS Annual Conference 2020 Blog Series.

Since the French economist, Thomas Piketty, published Capital in the 21st Century in 2014, it has become clear that we need to understand the development of wealth and income inequality in the long run. While Piketty traces inequality over the last 200 years, other economic historians have recently begun to explore inequality in the more distant past,[1] and they report striking similarities of increasing economic inequality from as early as 1450.

However, one major European region has been largely absent from the debate: Central Europe — the German cities and territories of the Holy Roman Empire. How did wealth inequality develop there? And what role did taxation play?

The Holy Roman Empire was vast, but its borders fluctuated greatly over time. As a first step to facilitating analysis, I focus on cities in the German-speaking regions. Urban wealth taxation developed early in many of the great cities, such as Cologne and Lübeck. By the fourteenth century, wealth taxes were common in many cities. They are an excellent source for getting a glimpse at wealth inequality (Caption 1).

Caption 1. Excerpt from the wealth tax registers of Lübeck (1774-84).

Three questions need to be clarified when using wealth tax registers as sources:

- Who was being taxed?

- What was being taxed?

- How were they taxed?

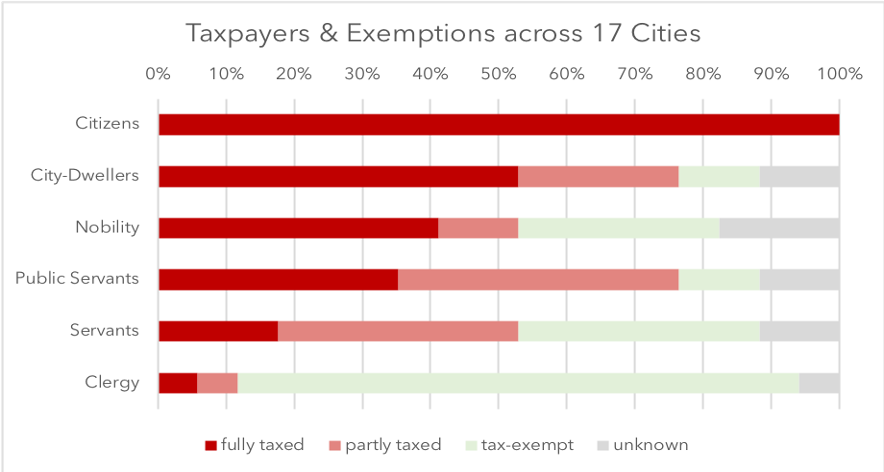

The first question was also crucial to contemporaries because the nobility and clergy adamantly defended their privileges which excluded them from taxation. It was Citizens and city-dwellers without citizenship who mainly bore the brunt of wealth taxation.

Figure 1. Taxpayers in a sample of 17 cities in the German Territories of the Holy Roman Empire.

Source: Data derived from multiple sources. For further information, please contact the author.

The cities’ tax codes reveal a level of sophistication that might be surprising. Not only did they tax real estate, cash and inventories, but many of them also taxed financial assets such as loans and perpetuities (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Taxable wealth in 19 cities in the German Territories of the Holy Roman Empire.

Source: Data derived from multiple sources. For further information, please contact the author.

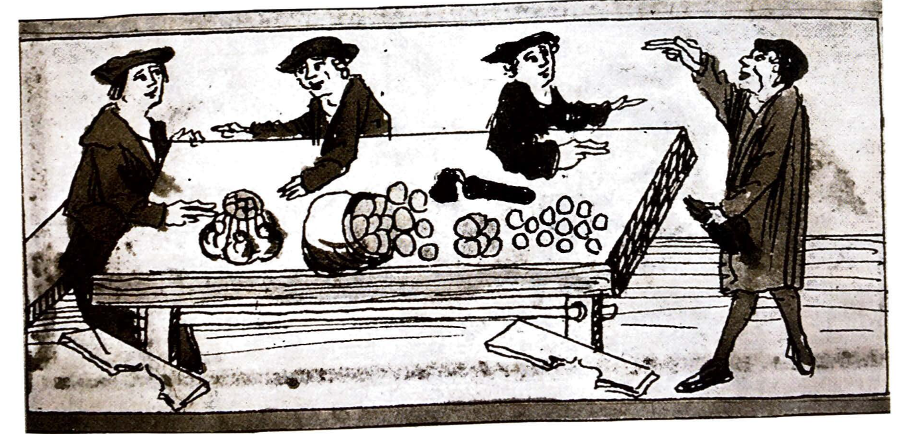

Wealth taxation was always proportional. Many cities established wealth thresholds below which citizens were exempt from taxation, and basic provisions such as grain, clothing and armour were also often exempt. Taxpayers were asked to estimate their own wealth and to pay the correct amount of taxes to the city’s tax collectors. To prevent fraud, taxpayers had to swear under oath (Caption 2).

Caption 2. Scene from the Volkacher Salbuch (1500-1504) shows the mayor on the left, two tax collectors at a table and a taxpayer delivering his tax payment while swearing his oath.

Taking the above limitations seriously, one can use tax registers to trace long-run wealth inequality in cities across the Holy Roman Empire (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gini Coefficients showing Wealth Inequality in the Urban Middle Ages.

Two main trends emerge: First, most cities experienced declining wealth inequality in the aftermath of the Black Death around 1350. The only exception was Rostock, an active trading city in the North. Second, from around 1500, inequality was rising in most cities until the onset of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). This war, in which large armies marauded through German lands bringing along plague and other diseases, as well as the shift in trade from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, might be the reason for the decline seen in this period. This sets the German lands apart from the development of inequality in other European regions, such as Italy and the Netherlands, in which inequality continued to rise throughout the early modern period.

Notes

[1] Milanovic, B., Lindert, P.H., and Williamson, J., ‘Pre-Industrial Inequality’, Economic Journal 121, no. 551 (2011): 255-272; Guido, A. ‘Economic Inequality in Northwestern Italy: A Long-Term View’, Journal of Economic History 75, no. 4 (2015): 1058-1096; Guido, A., and Ammannati, F., ‘Long-term trends in economic inequality: the case of the Florentine state, c.1300-1800’, Economic History Review 70, 4 (2017): 1072-1102; Wouter, R., ‘Economic Inequality and Growth before the Industrial Revolution: The Case of the Low Countries’, European Review of Economic History 20, no. 1 (2016): 1-22; Reis, J., ‘Deviant Behavior? Inequality in Portugal 1565-1770’, Cliometrica 11, no. 3 (2017): 297-319; Malinowski, M., and van Zanden J.L., ‘Income and Its Distribution in Preindustrial Poland’, Cliometrica 11, no. 3 (2017): 375-404.

Victoria Gierok: victoria.gierok@nuffield.ox.ac.uk