The Consumer Revolution Measured: What A New Price Index Reveals About Early Modern Industrialization And Industriousness

In this blog post Bas Spliet (University of Utrecht) and Anne E.C. McCants (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) introduce their research, currently available in Early View in the Economic History Review.

—

A vast body of literature has documented how successive generations in north-western Europe from the mid-seventeenth century onward accumulated ever more consumer goods on the margins of the household budget, despite the otherwise depressing picture of early modern purchasing power drawn by sticky wages and price inflation of necessities. But what was the cost of this consumer revolution?

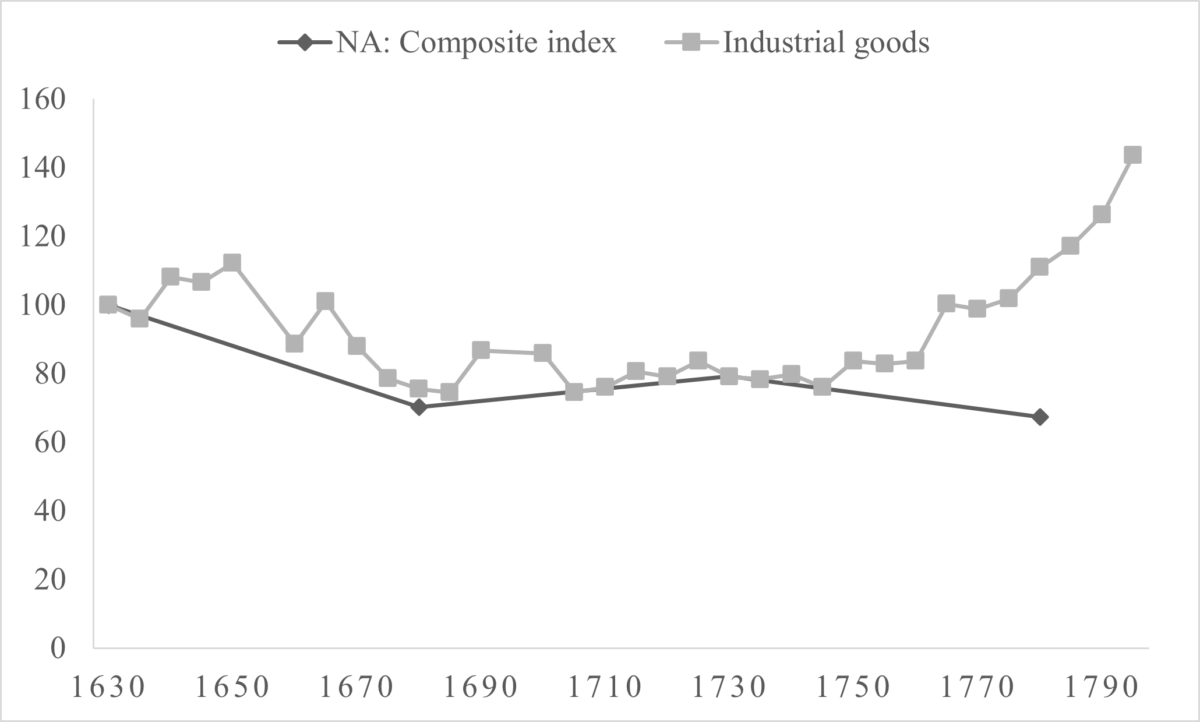

In a forthcoming article for the Economic History Review, we pose this question in a literal as well as in a metaphorical sense. We present a price index of ‘decencies’ constructed from a new dataset of probate inventories contained in Amsterdam’s notarial archives, permitting a quantitative examination of the hypothesis that, already before the industrial revolution, mass production and consumption were enabled by product and process innovations that made ‘new’, ‘semi-’, or ‘Populuxe’ luxuries affordable to growing segments of the preindustrial population. We find a 30 per cent reduction in the cost of furnishing a ‘respectable’ home and body among middling households during Amsterdam’s spectacular urban growth of the seventeenth century. This deflationary trend correlates with stock market prices (see figure 1) as well as with Holland’s economic and demographic growth. Rising productivity resulting from economies of scale thus formed the basis of the product and process innovations which we believe lay at the origins of the consumer revolution. The advances in windmill technology fuelling the expanding shipbuilding industry, for instance, also lowered the cost of paper for Dutch publishers and wooden furniture for Dutch homes – thus facilitating an expansion in book consumption and domestic comfort.

Not all innovations in manufacturing were achieved by productivity improvements, however. Alterations in the material composition of consumer products, rooted in a shift from intrinsic to design value which saw consumers increasingly choosing fashion over durability, were just as important. Decorated but fragile ceramics, for example, competed with the precious metals which had previously endowed tableware with use as well as store value. Material culture historians have long pointed to this social cost of the consumer revolution, and we present empirical evidence for it in the divergence between first- and second-hand prices over the eighteenth century (see figure 1), when Holland’s economic growth had run its course and labourers’ real wages started to decrease.

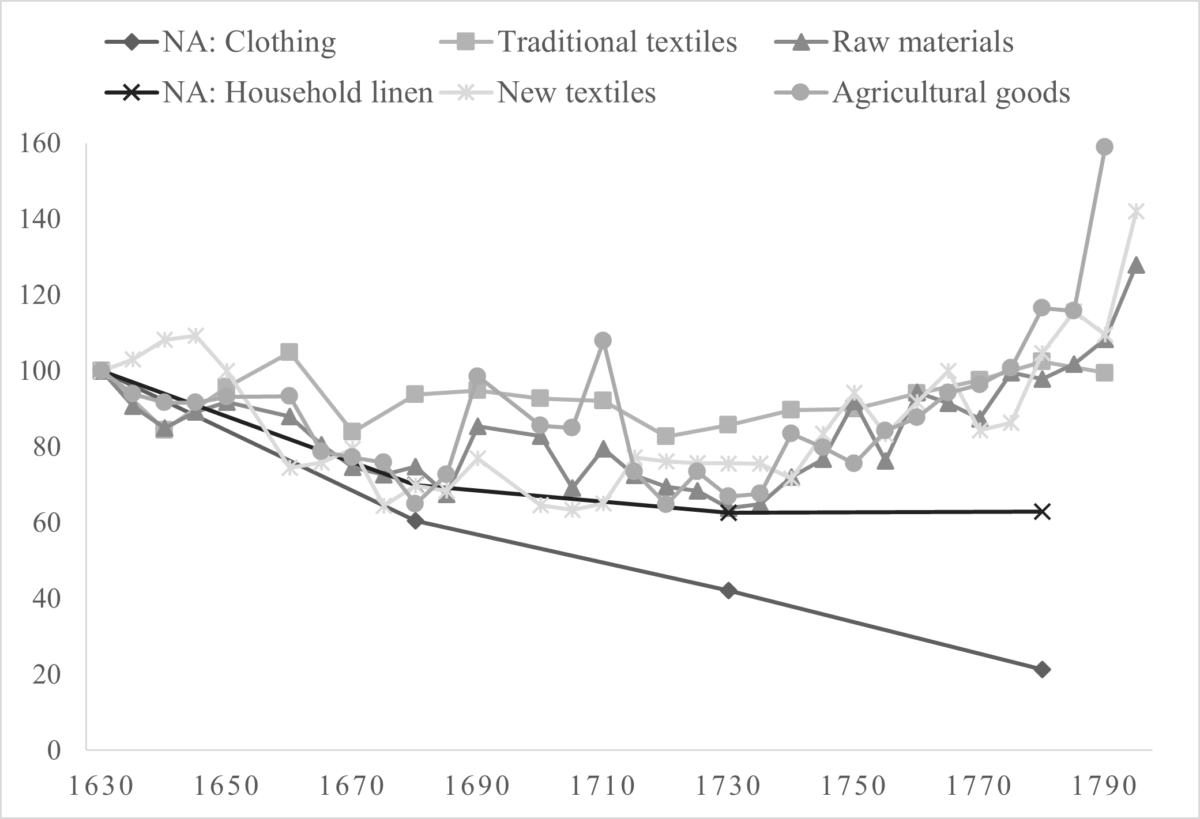

This contrast was starkest in clothing items (see figure 2). While in the seventeenth century the wardrobes of Amsterdam households expanded at least in part due to decreasing prices of raw and processed fibres, general price inflation made new textile products more expensive in the second half of the eighteenth century. At the same time, more frequent purchases were necessitated because the cotton-based and mixed textiles which increasingly dominated the culture of dress were not only sensitive to rapid changes in fashion but also wore out faster than traditional linen and woollen products. In the persistent decline of second-hand value in the face of rising first-hand prices we have clear evidence of the faster obsolescence of household and clothing objects. This troublesome feature of our contemporary problem of consumerism in other words has deep historical roots that stretch back before the industrial revolution.

This drawing from the late eighteenth century neatly captures Amsterdam’s consumer revolution in one image. Common workman could afford tobacco, coffee, and brandy, while broken earthenware litters the street.

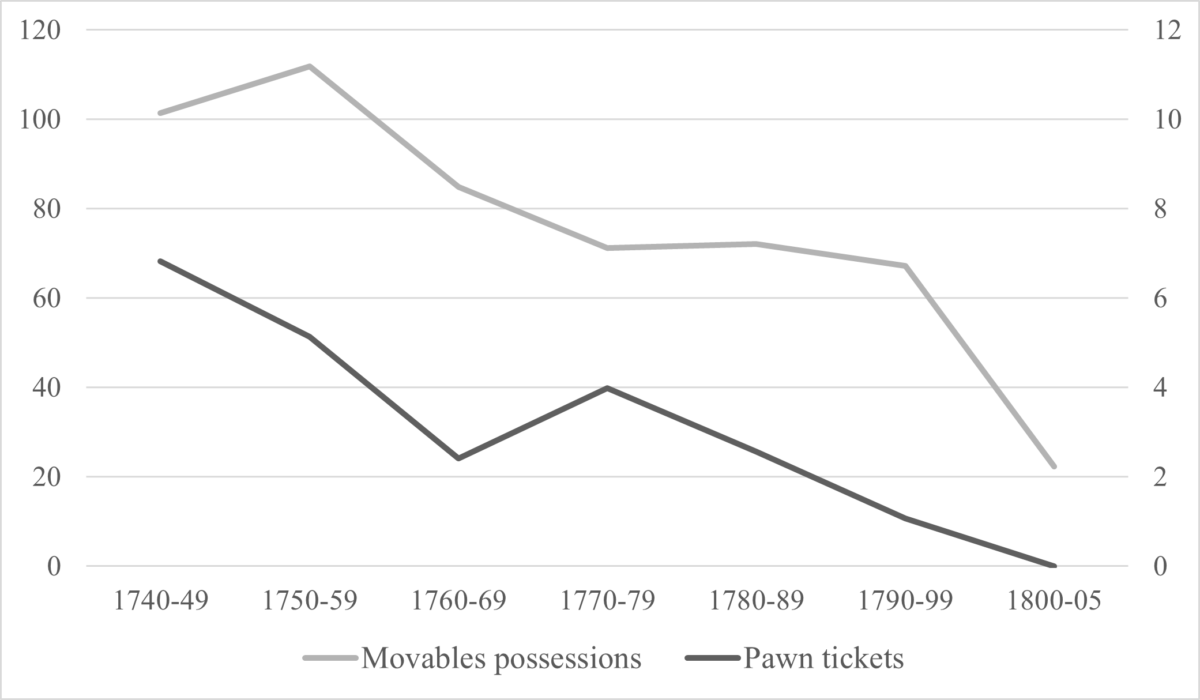

The metaphorical cost of the preindustrial consumer revolution can also be assessed on account of the broad social scope of our data, which integrate the new set of notarial inventories with an existing collection from the burgher orphanage. While the orphanage data from before mid-1782 were used in previous research, inventories from after that date are here presented for the first time. This provides a unique opportunity to gauge the endurance of the consumer transformations, in which the working classes initially partook, at a time of faltering real incomes. While we show in the paper that middling households maintained their elevated standard of living in this period, we also document the material impoverishment of labouring families (see figure 4). The fact that this process went hand-in-hand with their decreasing ability to resort to the pawnshop shows how the faster obsolescence of material possessions, in which clothing loomed largest as far as the poor were concerned, impacted the financial resilience of the most vulnerable members of metropolitan society. Working-class households may have come to own more than the proverbial clothes on their backs thanks to the consumer revolution, but in the end, it could not stop them from ending up living hand to mouth regardless.

Three implications for the broader historiography emerge from our results. First, the simultaneity in the decline of working-class real wages and material possessions indicate that the social reach of the consumer revolution beyond the middling sorts was predicated on stable, if not rising, purchasing power. Second, while Jan de Vries’ industrious revolution hypothesis has emphasized alterations in household production, we challenge the need for such demand-side theories in urban settings. Instead, finally, we reassert the importance of product and process innovations on the supply side lubricated by episodes of urban growth, which next to boosting aggregate demand ensured the economies of scale, specialization, and commercialization needed for productivity gains in the consumer industries.

To contact the authors:

Bas Spliet

b.r.spliet@uu.nl

University of Utrecht

Anne E.C. McCants

amccants@mit.edu

Massachusetts Institute of Technology