The historical and multilateral origins of the Paris Club: The South American chapter (1956-1965)

In this blog post Uziel González-Aliaga (University College London and Institute of Historical Research) presents their research, which was supported by the EHS Research Fund for Graduate Students.

—

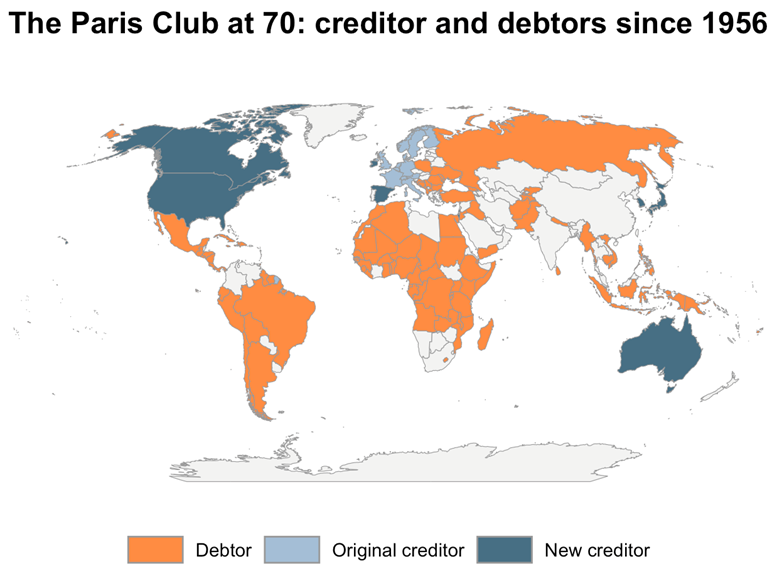

About 70 years ago, on 30 May 1956, delegates from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Britain signed the Act of Paris. Originally seeking to improve Argentina’s commercial standing in the European market, this landmark agreement set in motion a multilateral forum that has shaped the architecture of debt relief in the postwar era. Under the Paris Club aegis, creditor countries meet with a debtor nation to discuss the borrower’s external difficulties and decide on specific relief provisions, from payment reschedules to cancellations.

The first case of official debt restructuring in 1956-7 was followed by South American cases in the 1960s and a wave of sovereign defaults during the 1980s debt crisis. Since then, the Paris Club has consolidated its standing as a key piece in the global financial system. As of February 2026, participating countries have handled over US$600 billion worth of debt of 103 different sovereigns.

Given its international significance, it is not surprising that the Paris Club has featured in several traditions of scholarly investigations. Legal scholars have been interested in the application of key principles in sovereign workouts (Buchheit & Gulati, 2023), economists in refining models to untangle the effects of debt relief on growth and development (Cheng et al., 2018), while others have turned to the Club’s current challenges in the wake of new creditors joining the forum (Ballard-Rosa et al., 2025). Historical accounts of this key international institution, however, remain limited. A recent contribution by Thomas Callaghy (2026) reconstructs the early operations of debt relief and portrays the Club as a Bretton Woods institution in the likeness of the IMF or World Bank.

Building upon and challenging some of these recent findings, my project seeks to situate the Paris Club’s first decade in its wider international setting. It asks what specific institutional conditions explain the emergence of this multilateral forum, and why Argentina, Chile and Brazil featured in the first debt restructuring operations. In doing so, this research brings together global financial history literature, Latin American historiography, and themes of international political economy to argue that South American cases were instrumental in shaping modern principles of debt relief.

Enquiry into the historical origins of the Paris Club also speaks to the current contestation of the multilateral global economic order. By tracing the different institutional arrangements between creditors and debtors and charting how players consolidated non-discriminatory solutions, this project sheds light on the reasons for nation-states to arrange and maintain mechanisms of cooperation. It pays special attention to how wider global political and economic dynamics, from the Cold War to major international crises, prompted borrowers and lenders to avoid strictly bilateral venues. The informal and seemingly apolitical nature of the Paris Club offers a vantage point to look into the crafting of debt relief vis-à-vis the evolution of the global economic order.

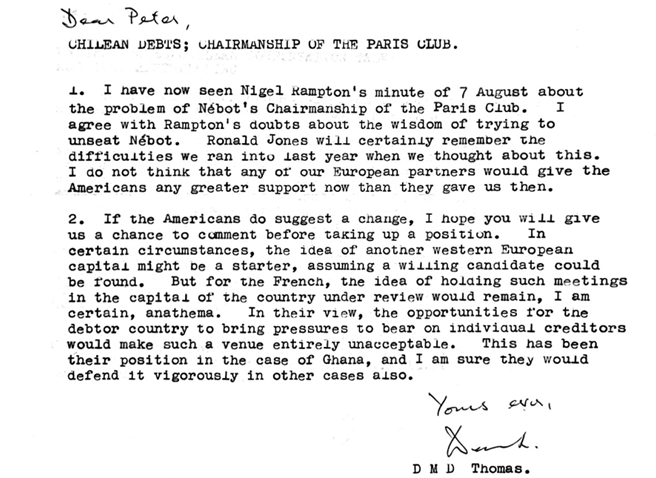

Much of this project leans heavily on archival records scattered through different geographies and languages. It employs historical records mostly untapped by previous researchers, including those of the debtor countries and the main Paris Club creditors, like the United Kingdom. These originally confidential or secret documents permit the reconstruction of debt rescheduling cases, and disentangle how countries balanced the need for external support with their own domestic and international policy goals. Equally interestingly, these records reveal serious disagreements among creditors and how their different views were ironed out, thus preserving the continuity of the multilateral forum. A good example comes from a critique advanced by British officials on the role of the French Chairman during the early 1970s:

The generous support of the EHS Research Fund will be instrumental in enriching the scope of primary sources for my project. With this assistance, I will be able to visit archives in the United States and France. Including the American and French perspectives on debt relief operations will grant this project greater precision and nuance, further enriching our contemporary understanding of the Paris Club’s complex history.

References:

Ballard-Rosa, C., Mosley, L., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2025). Paris Club Restructuring and the Rise of China, Princeton Sovereign Finance Lab, Princeton University.

Buchheit, L. C., & Gulati, M. (2023). Enforcing comparable treatment in sovereign debt workouts. Capital Markets Law Journal, 18(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/cmlj/kmac023

Callaghy, T. M. (2026). The Paris Club, 1956-1980: The Emergence of a Third Bretton Woods Sister (1st edn). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197839812.001.0001

Cheng, G., Díaz-Cassou, J., & Erce, A. (2018). Official debt restructurings and development. World Development, 111, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.003

To contact the author:

Uziel González-Aliaga

University College London and Institute of Historical Research