The Impact of Interest Rates in Eighteenth Century Ireland

Paul Kelly, the author of this blog, would like to thank the Economic History Society for the receipt of a grant from the Research Fund for Graduate Students to allow the author to access the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. In this blog post he introduces his research project.

—

The purpose of my research, which is a work in progress, is to construct the first detailed time series of interest rates in the Irish private credit markets of the eighteenth century.

The research addresses, amongst other things, two key economic questions. The first is a wide question of the role of institutional change in lowering interest rates. The second is specific to Ireland and relates to whether entrepreneurs there were handicapped by high interest rates and, if so, can this explain, to some extent, Ireland’s failure to industrialise?

North and Weingast argued that it was the institutional changes that accompanied the Glorious Revolution that led to the Financial Revolution in England with all the economic benefits that it brought. They also noted that the capital markets, particularly interest rates, provide one of the few measures of that effect. However, Ireland experienced few of the institutional benefits of the Glorious Revolution. For instance, there was no clear parliamentary supremacy and judicial appointments remained in the hands of the crown. So how and why did interest rates change?

We are fortunate in having a surviving remarkable source for Irish financial markets in the form of the Registry of Deeds, the ‘RoD’. Established in 1708 to help enforce the Penal Laws and prevent forgeries and fraudulent transactions ‘especially by Papists, to the great prejudice of the Protestant interest thereof’ it provides ‘memorials’ or summaries of sales or leases of landed property and mortgages.

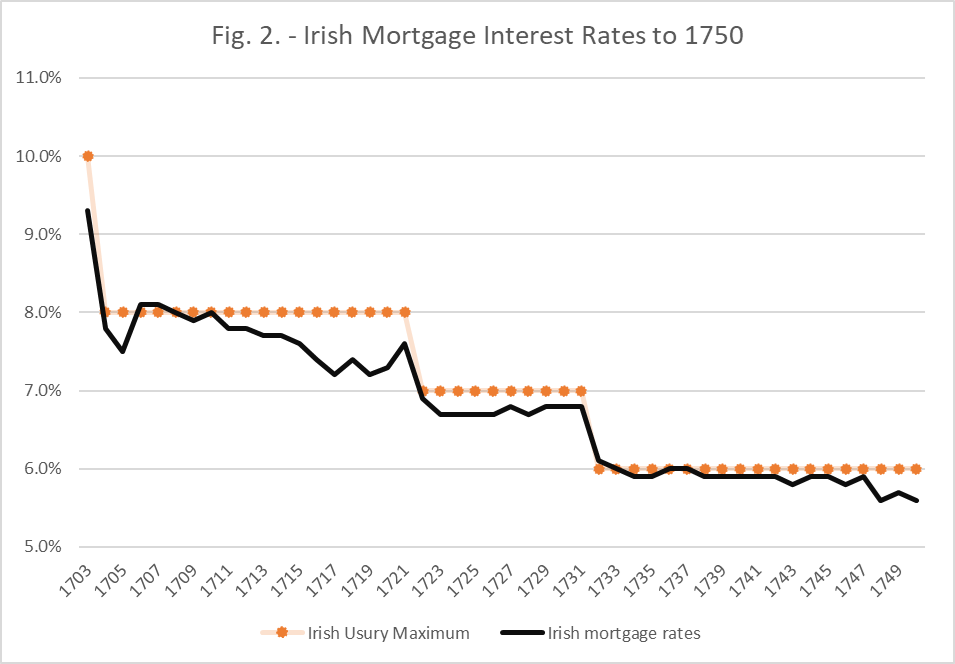

In Figure 2 I have presented the data mined on mortgage interest rates (note that the data prior to 1708 are sparse, but for each year after 1708 at least 40 datapoints have been collected).

Visually, there does appear to be a market trend in reducing rates in the period up to 1725, with an uptick in rates in 1720/1721 probably caused by the South Sea Bubble crisis. However, thereafter the reason for rates falling further is the statutory reduction in the maximum usury rate to 6% in 1732.

In summary then, in Ireland, a region under the same crown as England, but which enjoyed none of the ascribed benefits of the Glorious Revolution, market-driven mortgage interest rates declined by 3% in the period from 1688 to 1725, from 9.5% to 6.5%. In the same period, the equivalent English rates declined only by 1.5%. There are many possible explanations for the reduction in Irish rates, but one can be discounted. It cannot be attributed to the institutional changes of the Glorious Revolution since, if anything, these impacted the Irish economy in a negative rather than a positive way.

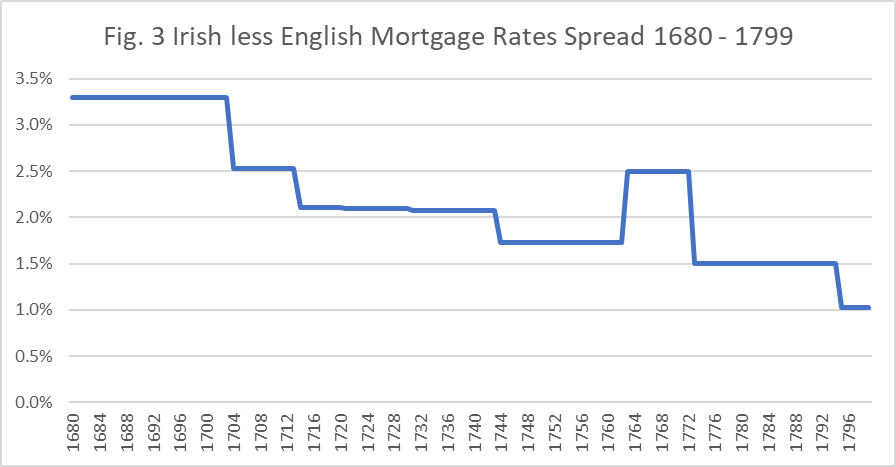

If Ireland enjoyed significant interest rate reductions at the beginning of the century, there was a sustained spread between Irish and English interest rates, perhaps reflecting a political risk premium.

The economic disadvantages of higher interest rates were fully understood by contemporary commentators. For instance, James Laffan of Kilkenny, in a pamphlet of 1785 calculated that the annual cost of running a ship of £1,000 capital value was £197 in Ireland compared to £158 in England, the difference being caused solely by the interest rate differential. Who therefore would choose to build ships and trade from Ireland rather than England? In addition to the high relative rate of interest as noted above, the stagnant nature of the Irish credit market, with few deals in the latter part of the century being made at any rate other than the usury rate, would presumably have reduced the supply of credit. Hardly ideal conditions for an entrepreneur.

However, the thing about Irish history, to paraphrase Yeatman and Seller, is just when you think you’ve solved the Irish question, a new question arises. In this case, if the Irish credit market was so moribund – how did Dublin grow to be the second largest city in the British Empire by the end of the eighteenth century?

Thus, as you see, I have, at present, only partial answers to the questions I posed at the outset and I am also undertaking more work on the returns to investors from land as opposed to mortgages, where the RoD is also a key source. Ultimately, I hope that this additional work will allow a more detailed quantification of the evolution of Irish GDP over the eighteenth century and beyond.

To contact the author:

Paul Kelly

https://lse.academia.edu/paulkelly

London School of Economics