The Long View on Epidemics, Disease and Public Health: Research from Economic History – Part A

This piece is the result of a collaboration between the Economic History Review, the Journal of Economic History, Explorations in Economic History and the European Review of Economic History. More details and special thanks below. Part B can be found here.

As the world grapples with a pandemic, informed views based on facts and evidence have become all the more important. Economic history is a uniquely well-suited discipline to provide insights into the costs and consequences of rare events, such as pandemics, as it combines the tools of an economist with the long perspective and attention to context of historians. The editors of the main journals in economic history have thus gathered a selection of the recently-published articles on epidemics, disease and public health, generously made available by publishers to the public, free of access, so that we may continue to learn from the decisions of humans and policy makers confronting earlier episodes of widespread disease and pandemics.

Generations of economic historians have studied disease and its impact on societies across history. However, as the discipline has continued to evolve with improvements in both data and methods, researchers have uncovered new evidence about episodes from the distant past, such as the Black Death, as well as more recent global pandemics, such as the Spanish Influenza of 1918. We begin with a recent overview of scholarship on the history of premodern epidemics, and group the remaining articles thematically, into two short reading lists. The first consists of research exploring the impact of diseases in the most direct sense: the patterns of mortality they produce. The second group of articles explores the longer-term consequences of diseases for people’s health later in life.

Patterns of Mortality

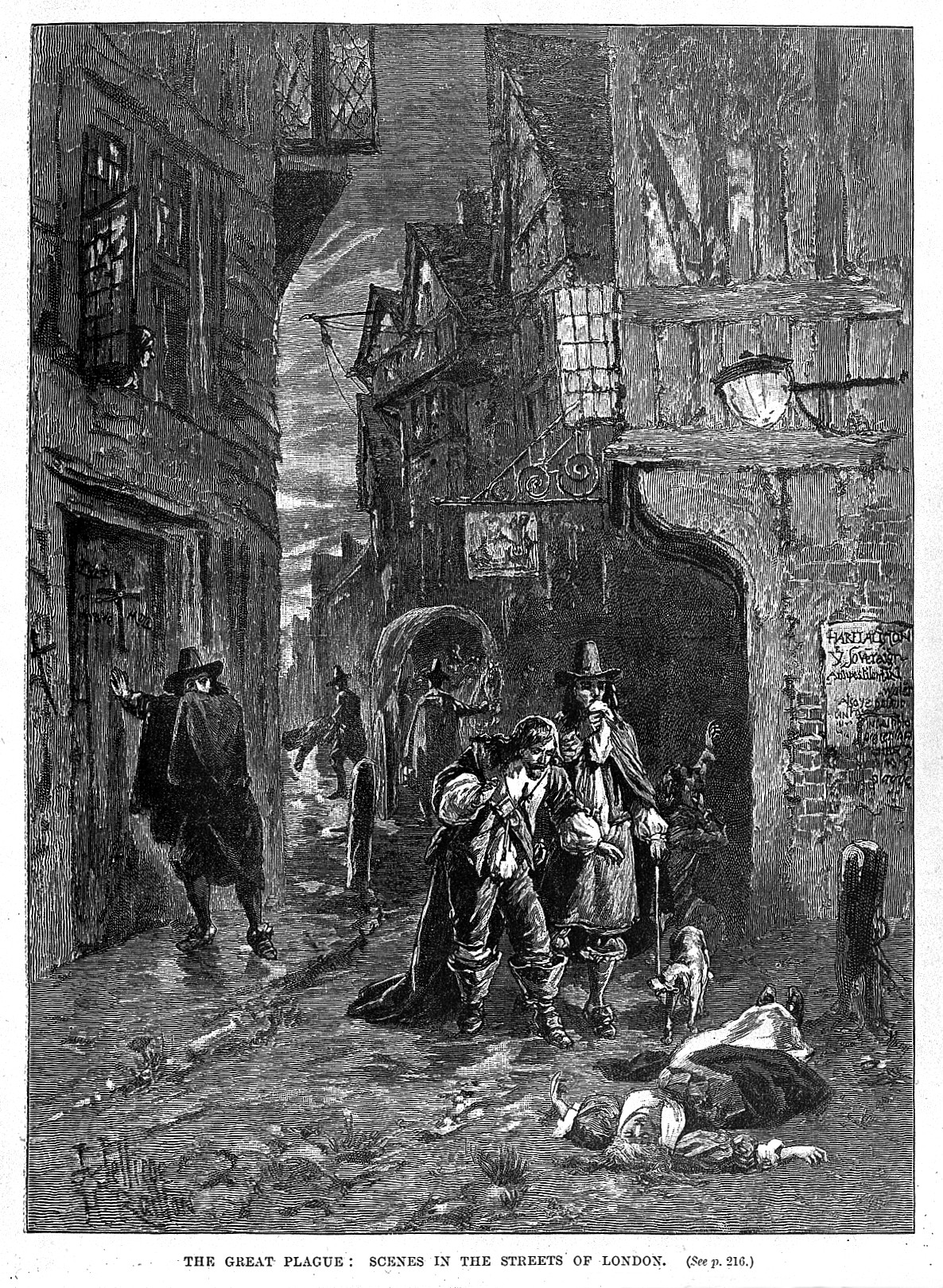

The rich and complex body of historical work on epidemics is carefully surveyed by Guido Alfani and Tommy Murphy who provide an excellent guide to the economic, social, and demographic impact of plagues in human history: ‘Plague and Lethal Epidemics in the Pre-Industrial World’. The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 1 (2017): 314–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050717000092. The impact of epidemics varies over time and few studies have shown this so clearly as the penetrating article by Neil Cummins, Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda, who provide a finely-detailed map of how the plague evolved in 16th and 17th century London to reveal who was most heavily burdened by this contagion. ‘Living Standards and Plague in London, 1560–1665’. Economic History Review 69, no. 1 (2016): 3-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12098 . Plagues shaped the history of nations and, indeed, global history, but we must not assume that the impact of plagues was as devastating as we might assume: in a classic piece of historical detective work, Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis show that mortality among native Americans in the Hudson Bay area was much lower than historians had suggested: ‘Smallpox and Native American Mortality: The 1780s Epidemic in the Hudson Bay Region’. Explorations in Economic History 49, no. 3 (2012): 277-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2012.04.003

The effects of disease reflect a complex interaction of individual and social factors. A paper by Karen Clay, Joshua Lewis and Edson Severnini explains how the combination of air pollution and influenza was particularly deadly in the 1918 epidemic, and that cities in the US which were heavy users of coal had all-age mortality rates that were approximately 10 per cent higher than those with lower rates of coal use: ‘Pollution, Infectious Disease, and Mortality: Evidence from the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic’. The Journal of Economic History 78, no. 4 (2018): 1179–1209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002205071800058X. A remarkable analysis of how one of the great killers, smallpox, evolved during the 18th century, is provided by Romola Davenport, Leonard Schwarz and Jeremy Boulton, who concluded that it was a change in the transmissibility of the disease itself that mattered most for its impact: “The Decline of Adult Smallpox in Eighteenth‐century London.” Economic History Review 64, no. 4 (2011): 1289-314. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2011.00599.x The question of which sections of society experienced the heaviest burden of sickness during outbreaks of disease outbreaks has long troubled historians and epidemiologists. Outsiders and immigrants have often been blamed for disease outbreaks. Jonathan Pritchett and Insan Tunali show that poverty and immunisation, not immigration, explain who was infected during the Yellow Fever epidemic in 1853 New Orleans: ‘Strangers’ Disease: Determinants of Yellow Fever Mortality during the New Orleans Epidemic of 1853’. Explorations in Economic History 32, no. 4 (1995): 517. https://doi.org/10.1006/exeh.1995.1022

The Long Run Consequences of Disease

The way epidemics affects families is complex. John Parman wrestles wit h one of the most difficult issues – how parents respond to the harms caused by exposure to an epidemic. Parman shows that parents chose to concentrate resources on the children who were not affected by exposure to influenza in 1918, which reinforced the differences between their children: ‘Childhood Health and Sibling Outcomes: Nurture Reinforcing Nature during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic’, Explorations in Economic History 58 (2015): 22-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2015.07.002. Martin Saavedra addresses a related question: how did exposure to disease in early childhood affect life in the long run? Using late 19th century census data from the US, Saavedra shows that children of immigrants who were exposed to yellow fever in the womb or early infancy, did less well in later life than their peers, because they were only able to secure lower-paid employment: ‘Early-life Disease Exposure and Occupational Status: The Impact of Yellow Fever during the 19th Century’. Explorations in Economic History 64, no. C (2017): 62-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2017.01.003. One of the great advantages of historical research is its ability to reveal how the experiences of disease over a lifetime generates cumulative harms. Javier Birchenall’s extraordinary paper shows how soldiers’ exposure to disease during the American Civil War increased the probability they would contract tuberculosis later in life: ‘Airborne Diseases: Tuberculosis in the Union Army’. Explorations in Economic History 48, no. 2 (2011): 325-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2011.01.004

Patrick Wallis, Giovanni Federico & John Turner, for the Economic History Review;

Dan Bogart, Karen Clay, William Collins, for the Journal of Economic History;

Kris James Mitchener, Carola Frydman, and Marianne Wanamaker, for Explorations in Economic History;

Joan Roses, Kerstin Enflo, Christopher Meissner, for the European Review of Economic History.

If you wish to read further, other papers on this topic are available on the journal websites:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)1468-0289.epidemics-disease-mortality

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-economic-history/free-articles-on-pandemics

* Thanks to Leigh Shaw-Taylor, Cambridge University Press, Elsevier, Oxford University Press, and Wiley, for their advice and support.