The Paradox of Redistribution in time: Social spending in 54 countries, 1967-2018

By Xabier García Fuente (Universitat de Barcelona)

This research was presented in the sixth New Researcher Online Session: ‘Spending & Networks’.

—

Why are some countries more redistributive than others? This question is central to current welfare state politics, especially in view of rising levels of inequality and the ensuing social tensions. Since coming to power in 2019, Brazil’s far-right government has restricted access to Bolsa Familia—a conditional cash-transfer program—despite its success at reducing poverty with a very low cost (less than 0.5% of national GDP). In richer countries, the social-democratic project is said to be obsolete, as left-wing parties forsake egalitarian policies to cater to economic winners (Piketty, 2020).

How can we make sense of this sort of distributive conflict? Are there common patterns in rich and middle-income countries? My research suggests that welfare state institutions show great inertia, so we need to observe the origins of social policies to explain current redistributive outcomes. Initial policy positions —how pro-poor or pro-rich social transfers were— determine what groups emerge as net winners or net losers when social expenditure increases, which crucially affects the viability and direction of policy change.

Korpi and Palme (1998) famously suggested the existence of a Paradox of Redistribution: ‘the more we target benefits at the poor … the less likely we are to reduce poverty and inequality’. In their framework, progressive programs may be more redistributive per euro spent, but they generate zero-sum conflicts between the poor and the middle-class and obstruct the formation of redistributive political coalitions. In contrast, universal programs align the preferences of the poor and the middle-class and lead to bigger, more egalitarian welfare states. In sum, redistribution increases as transfers become bigger and less pro-poor.

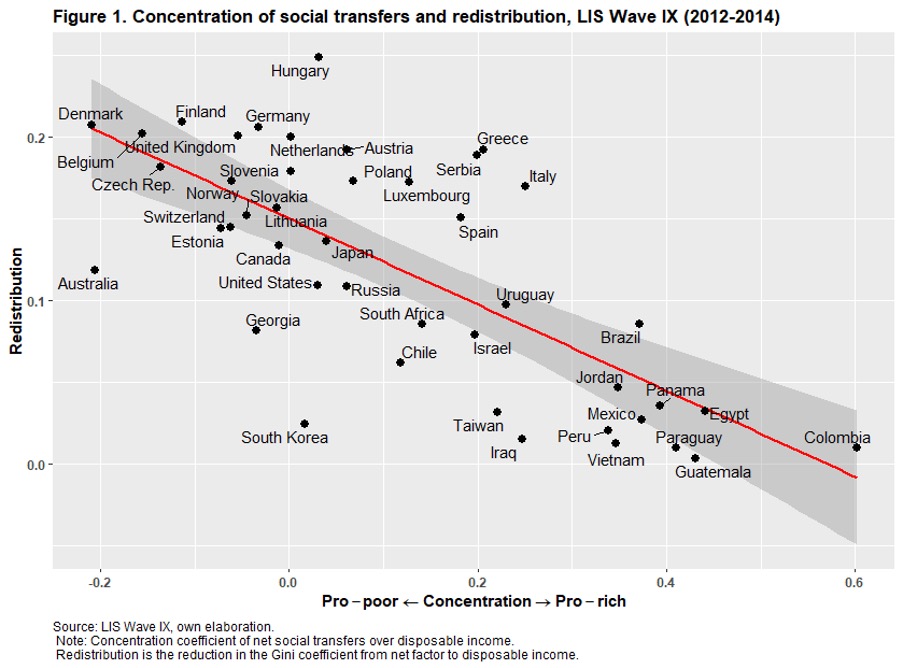

Using survey micro-data provided by the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), my research updates Korpi and Palme’s (1998) study and addresses two gaps. First, I extend the sample to 54 rich and middle-income countries, including elitist welfare states in Latin America and other middle-income countries. As Figure 1 shows, extending the sample would clearly refute the Paradox: redistribution is higher in more pro-poor countries.

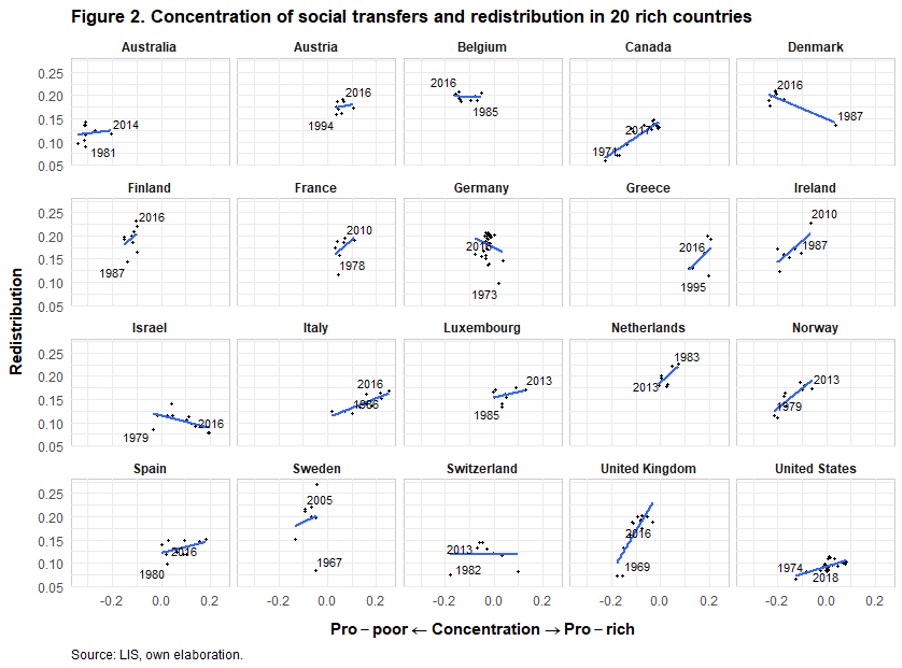

Second, in line with the dynamic political arguments suggested in the Paradox, I explore the evolution of social transfers and redistribution within countries over time. Overall, countries have increased redistribution by making their transfers less pro-poor, which matches the predictions of the Paradox (see Figure 2). The relationship is especially strong in Ireland, Canada, United Kingdom and Norway. Parting from highly progressive (pro-poor) policy positions, these countries have improved redistribution increasing expenditure and reducing their bias towards the poor.

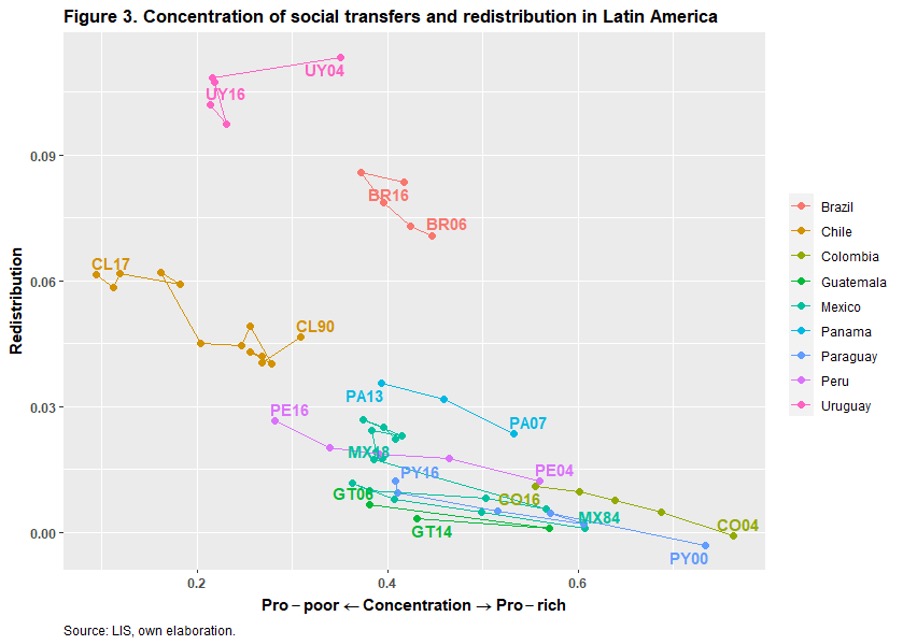

Latin American countries are a notorious exception to this pattern. They are markedly pro-rich and, contrary to the cases above, they have improved redistribution very modestly by becoming more pro-poor (see Figure 3).

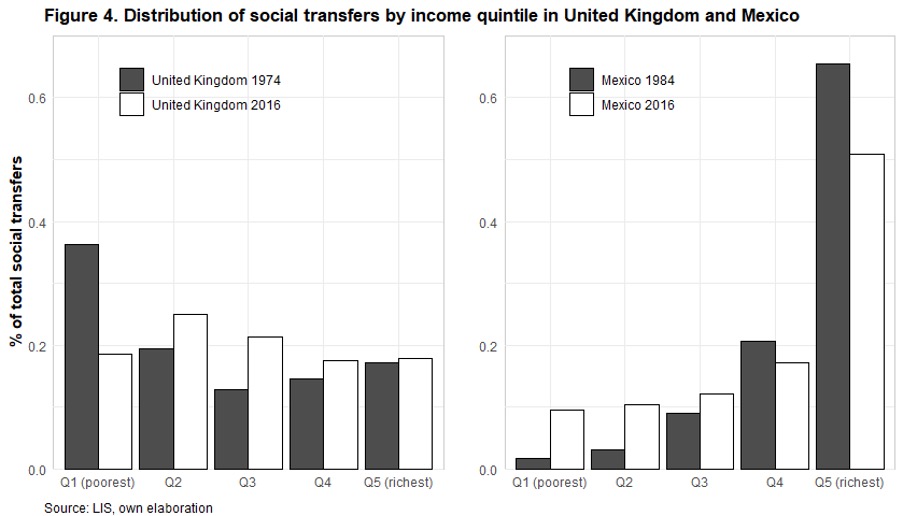

What does it mean that redistribution increases as transfers become more or less pro-poor? United Kingdom and Mexico provide a good example (see Figure 4). In the United Kingdom, redistribution through social transfers increased from 7 Gini points in 1974 to 19 Gini points in 2016. In the same period, the share of total social transfers received by the poorest 20% of the population decreased from 35% to 18%. In Mexico, the share of total social transfers obtained by the poorest 20% went from 2% in 1984 to 10% in 2016, while the share obtained by the richest 20% decreased from 66% to 51%. Yet, despite these advances, redistribution through social transfers in Mexico remains very low (2.5 Gini points in 2016, from 0.1 Gini points in 1984).

Conclusions

In countries with pro-poor social transfers, extending coverage involves reaching up the income ladder to include richer constituencies, which narrows the gap between net winners and net losers. This reduces the salience of distributive conflicts and eases welfare state expansion, leading to higher redistribution. However, as transfers become more pro-rich the margin to leverage the progressivity-size trade-off narrows, which helps explain the inability of current welfare states to increase redistribution as inequality rises.

In countries with pro-rich social transfers, extending coverage involves reaching down the income ladder to include the poor. Launching programs for the poor requires rising taxes or cutting the benefits of privileged insiders, which creates a clearly delineated gap between net winners and net losers. This increases the salience of distributive conflicts, leading to smaller, less egalitarian welfare states.

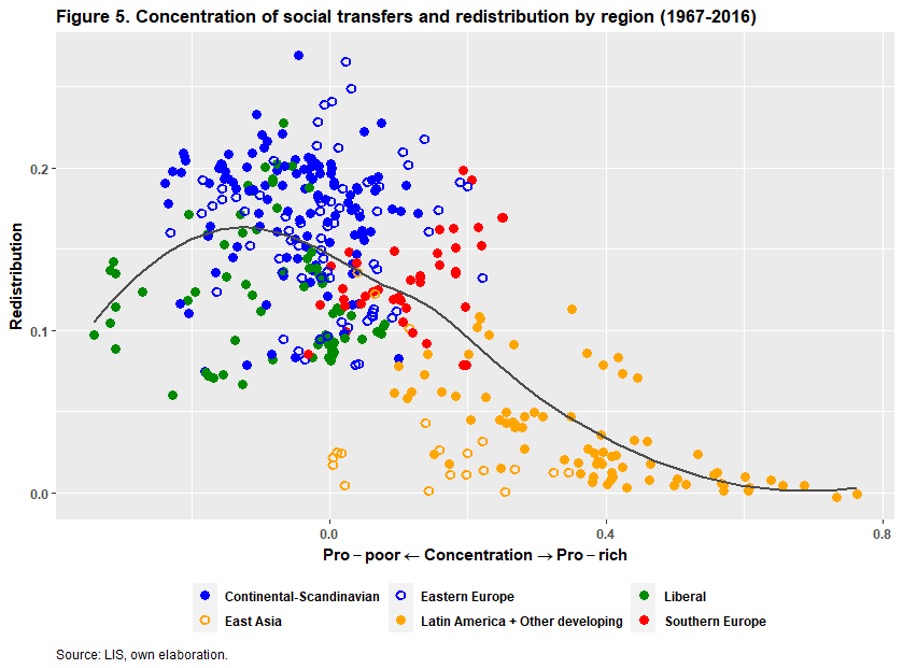

In sum, social policy design is very persistent because it crucially shapes distributive conflicts. Advanced welfare states have increased redistribution by getting bigger and less progressive (less pro-poor). This fits with historical evidence that advanced welfare states grew from minimalist cores, but it also describes contemporary policy change. Following this same reasoning, elitist welfare states in developing regions will find it difficult to become more egalitarian. Figure 5 shows the persistency of distributive outcomes across welfare regimes.

—

Xabier García Fuente

Twitter: @xabigarf

References

Korpi, W. and Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5):661–687.

Piketty, T. (2020). Capital and Ideology. Harvard University Press.