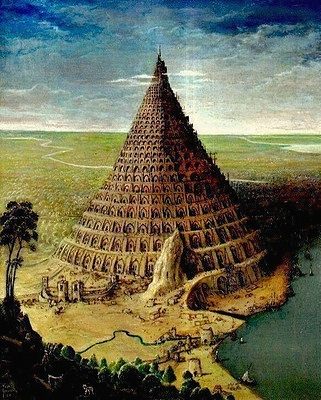

The TOWER OF BABEL: why we are still a long way from everyone speaking the same language

Nearly a third of the world’s 6,000 plus distinct languages have more than 35,000 speakers. But despite the big communications advantages of a few widely spoken languages such as English and Spanish, there is no sign of a systematic decline in the number of people speaking this large group of relatively small languages.

These are among the findings of a new study by Professor David Clingingsmith, published in the February 2017 issue of the Economic Journal. His analysis explains how it is possible to have a stable situation in which the world has a small number of very large languages and a large number of small languages.

Does this mean that the benefits of a universal language could never be so great as to induce a sweeping consolidation of language? No, the study concludes:

‘Consider the example of migrants, who tend to switch to the language of their adopted home within a few generations. When the incentives are large enough, populations do switch languages.’

‘The question we can’t yet answer is whether recent technological developments, such as the internet, will change the benefits enough to make such switching worthwhile more broadly.’

Why don’t all people speak the same language? At least since the story of the Tower of Babel, humans have puzzled over the diversity of spoken languages. As with the ancient writers of the book of Genesis, economists have also recognised that there are advantages when people speak a common language, and that those advantages only increase when more people adopt a language.

This simple reasoning predicts that humans should eventually adopt a common language. The growing role of English as the world’s lingua franca and the radical shrinking of distances enabled by the internet has led many people to speculate that the emergence of a universal human language is, if not imminent, at least on the horizon.

There are more than 6,000 distinct languages spoken in the world today. Just 16 of these languages are the native languages of fully half the human population, while the median language is known by only 10,000 people.

The implications might appear to be clear: if we are indeed on the road to a universal language, then the populations speaking the vast majority of these languages must be shrinking relative to the largest ones, on their way to extinction.

The new study presents a very different picture. The author first uses population censuses to produce a new set of estimates of the level and growth of language populations.

The relative paucity of data on the number of people speaking the world’s languages at different points in time means that this can be done for only 344 languages. Nevertheless, the data clearly suggest that the populations of the 29% of languages that have 35,000 or more speakers are stable, not shrinking.

How could this stability be consistent with the very real advantages offered by widely spoken languages? The key is to realise that most human interaction has a local character.

This insight is central to the author’s analysis, which shows that even when there are strong benefits to adopting a common language, we can still end up in a world with a small number of very large languages and a large number of small ones. Numerical simulations of the analytical model produce distributions of language sizes that look very much like the one that actually obtain in the world today.

Summary of the article ‘Are the World’s Languages Consolidating? The Dynamics and Distribution of Language Populations’ by David Clingingsmith. Published in Economic Journal on February 2017