Unequal access to food during the nutritional transition: evidence from Mediterranean Spain

by Francisco J. Medina-Albaladejo & Salvador Calatayud (Universitat de València).

This article is forthcoming in the Economic History Review.

Over the last century, European historiography has debated whether industrialisation brought about an improvement in working class living standards. Multiple demographic, economic, anthropometric and wellbeing indicators have been examined in this regard, but it was Eric Hobsbawm (1957) who, in the late 1950s, incorporated food consumption patterns into the analysis.

Between the mid-19th and the first half of the 20th century, the diet of European populations underwent radical changes. Caloric intake increased significantly, and cereals were to a large extent replaced by animal proteins and fat, resulting from a substantial increase in meat, milk, eggs and fish consumption. This transformation was referred to by Popkin (1993) as the ‘Nutritional transition’.

These dietary changes were driven, inter alia, by the evolution of income levels which raises the possibility that significant inequalities between different social groups ensued. Dietary inequalities between different social groups are a key component in the analysis of inequality and living standards; they directly affect mortality, life expectancy, and morbidity. However, this hypothesis remains unproven, as historians are still searching for adequate sources and methods with which to measure the effects of dietary changes on living standards.

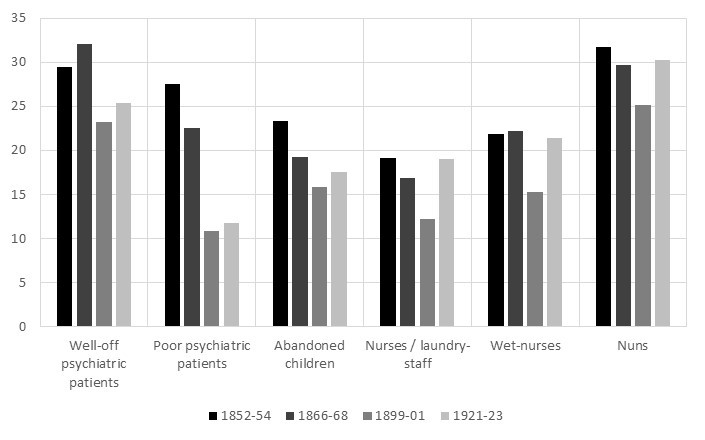

This study contributes to the debate by analysing a relatively untapped source: hospital diets. We have analysed the diet of psychiatric patients and members of staff in the main hospital of the city of Valencia (Spain) between 1852 and 1923. The diet of patients depended on their social status and the amounts they paid for their upkeep. ‘Poor psychiatric patients’ and abandoned children, who paid no fee, were fed according to hospital regulations, whereas ‘well-off psychiatric patients’ paid a daily fee in exchange for a richer and more varied diet. There were also differences among members of staff, with nuns receiving a richer diet than other personnel (launderers, nurses and wet-nurses). We think that our source broadly reflects dietary patterns of the Spanish population and the effect of income levels thereon.

Figure 2 illustrates some of these differences in terms of animal-based caloric intake in each of the groups under study. Three population groups can be clearly distinguished: ‘well-off psychiatric patients’ and nuns, whose diet already presented some of the features of the nutritional transition by the mid-19th century, including fewer cereals and a meat-rich diet, as well as the inclusion of new products, such as olive oil, milk, eggs and fish; hospital staff, whose diet was rich in calories,to compensate for their demanding jobs, but still traditional in structure, being largely based on cereals, legumes, meat and wine; and, finally, ‘poor psychiatric patients’ and abandoned children, whose diet was poorer and which, by the 1920, had barely joined the trends that characterised the nutritional transition.

In conclusion, the nutritional transition was not a homogenous process, affecting all diets at the time or at the same pace. On the contrary, it was a process marked by social difference, and the progress of dietary changes was largely determined by social factors. By the mid-19th century, the diet structure of well-to-do social groups resembled diets that were more characteristic of the 1930s, while less favoured and intermediate social groups had to wait until the early 20th century before they could incorporate new foodstuffs into their diet. As this sequence clearly indicates, less favoured social groups always lagged behind.

References

Medina-Albaladejo, F. J. and Calatayud, S., “Unequal access to food during the nutritional transition: evidence from Mediterranean Spain”, Economic History Review, (forthcoming).

Hobsbawm, E. J., “The British Standard of Living, 1790-1850”, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., X (1957), pp. 46-68.

Popkin B. M., “Nutritional Patterns and Transitions”, Population and Development Review, 19, 1 (1993), pp. 138-157.