WELFARE SPENDING DOESN’T ‘CROWD OUT’ CHARITABLE WORK: Historical evidence from England under the Poor Laws

Cutting the welfare budget is unlikely to lead to an increase in private voluntary work and charitable giving, according to research by Nina Boberg-Fazlic and Paul Sharp.

Their study of England in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, published in the February 2017 issue of the Economic Journal, shows that parts of the country where there was increased spending under the Poor Laws actually enjoyed higher levels of charitable income.

The authors conclude:

‘Since the end of the Second World War, the size and scope of government welfare provision has come increasingly under attack.’

‘There are theoretical justifications for this, but we believe that the idea of ‘crowding out’ – public spending deterring private efforts – should not be one of them.’

‘On the contrary, there even seems to be evidence that government can set an example for private donors.

Why does Europe have considerably higher welfare provision than the United States? One long debated explanation is the existence of a ‘crowding out’ effect, whereby government spending crowds out private voluntary work and charitable giving. The idea is that taxpayers feel that they are already contributing through their taxes and thus do not contribute as much privately.

Crowding out makes intuitive sense if people are only concerned with the total level of welfare provided. But many other factors might play a role in the decision to donate privately and, in fact, studies on this topic have led to inconclusive results.

The idea of crowding out has also caught the imagination of politicians, most recently as part of the flagship policy of the UK’s Conservative Party in the 2010 General Election: the so-called ‘big society’. If crowding out holds, spending cuts could be justified by the notion that the private sector will take over.

The new study shows that this is not necessarily the case. In fact, the authors provide historical evidence for the opposite. They analyse data on per capita charitable income and public welfare spending in England between 1785 and 1815. This was a time when welfare spending was regulated locally under the Poor Laws, which meant that different areas in England had different levels of spending and generosity in terms of who received how much relief for how long.

The research finds no evidence of crowding out; rather, it finds that parts of the country with higher state provision of welfare actually enjoyed higher levels of charitable income. At the time, Poor Law spending was increasing rapidly, largely due to strains caused by the Industrial Revolution. This increase occurred despite there being no changes in the laws regulating relief during this period.

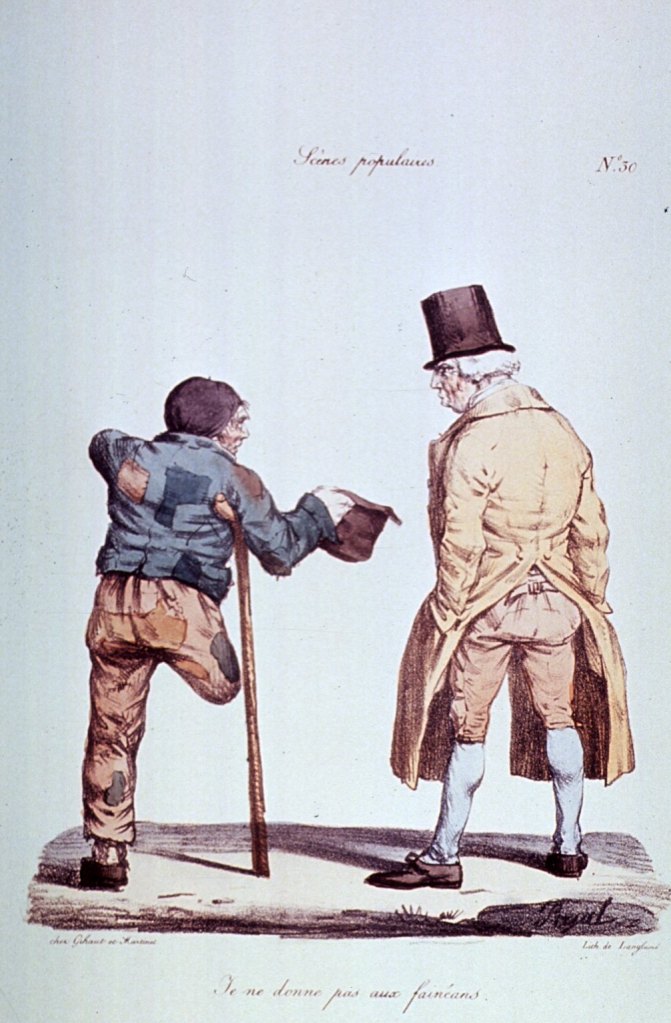

The increase in Poor Law spending led to concerns among contemporary commentators and economists. Many expressed the belief that the increase in spending was due to a disincentive effect of poor relief and that mandatory contributions through the poor rate would crowd out voluntary giving, thereby undermining social virtue. That public debate now largely repeats itself two hundred years later.

Summary of the article ‘Does Welfare Spending Crowd Out Charitable Activity? Evidence from Historical England under the Poor Laws’ by Nina Boberg-Fazlic (University of Duisberg-Essen) and Paul Sharp (University of Southern Denmark). Published in Economic Journal, February 2017