When Mercy Became Planning: Italy’s Foundling Wheels and the Hidden Economics of Abandonment

This blog post by Marco Molteni (University of Turin) and Giuliana Freschi (Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa) introduces their recent research published in Explorations in Economic History.

—

‘‘I have seen Garibaldi crying only twice.

The first one was when we visited the foundlings’ home in Palermo.

The second one, when we visited the foundlings’ home in Naples’’

[Jessie White Mario (1897), Writer, philanthropist, and Garibaldi’s nurse in four wars]

A medieval invention is back. Across Europe, “baby hatches”—modern versions of the foundling wheel—are being installed by advocates as a life-saving last resort for desperate mothers. Opponents, from the UN to adoption-rights groups, argue they violate a child’s right to an identity and may not even save lives.

But what was the original foundling wheel, the ruota degli esposti? It was not merely a neutral safety net. It was a powerful institution of social control. In 19th-century Italy, it was designed to solve the “problem” of illegitimate births. In a society that deemed unwed mothers unfit and a source of shame, the ruota compelled them to abandon their children to preserve “honour.” It upheld a rigid social morality by making the child—and the “sin”—disappear.

This social function, however, concealed a different economic reality. Our recent historical research on the Italian foundling wheel examines what actually happened when these wheels were abolished. By examining yearly records from Italian provinces over a two-decade period, a revealing pattern emerged: provinces abolished their wheels at different times, offering a rare opportunity to understand the wheels’ actual impact.

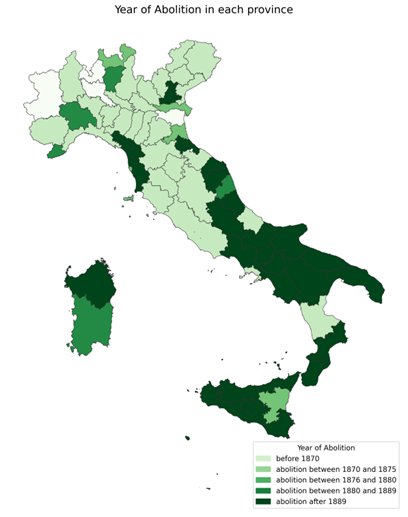

The geography of Italy’s foundling wheels tells its own story. In 1863 the ruota was present throughout the country. Yet, within two decades, this landscape underwent a transformation. As Figure 1 shows, the abolition movement began in the North—more industrialized and less attached to traditional moral frameworks—and gradually spread southward, with provinces eliminating their wheels systems at strikingly different moments. This uneven timeline proved historically revealing. Because the wheels didn’t disappear all at once, but instead rolled away gradually across the peninsula, we can observe what actually changed when each province decided to close its doors. The evidence is striking. The 19th-century critics of the foundling wheel were right.

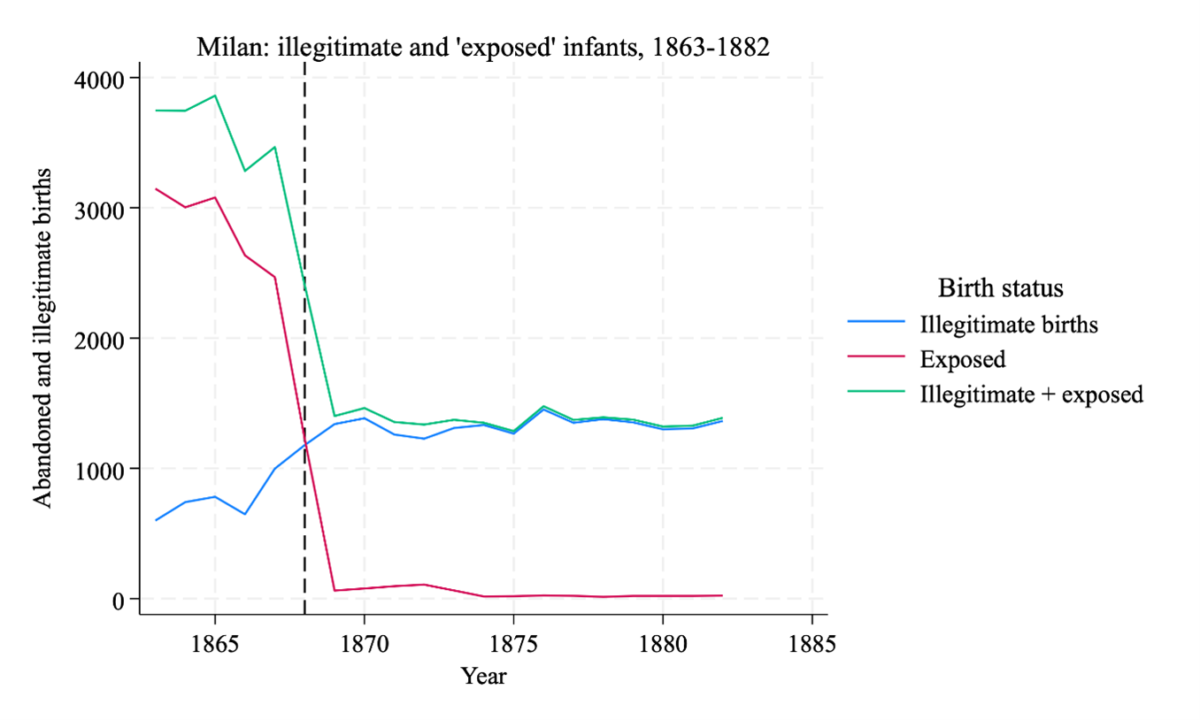

First, abolishing the wheel caused a dramatic decrease in child abandonment by more than 50%. The effect was immediate. As Figure 2 displays, when Milan closed its ruota in 1868, the number of infants left at the wheel plummeted to near zero almost overnight. Yet alongside this decline, the recorded number of “illegitimate births” rose. This was not a sudden surge in illegitimate conceptions, but rather a shift in how births were registered. Without the wheel’s anonymity, unwed mothers were forced to register their children through official channels, where the child’s “illegitimate” status was openly recorded. Even accounting for this change in record-keeping, the overall number of abandoned children fell sharply.

Second, closing the wheels saved lives. Infant death rates declined noticeably by ca. 10%. The anonymous system had encouraged so many abandonments that foundling homes became overcrowded and disease-ridden. Fewer abandoned infants meant better survival chances for all the children in these institutions.

Third, anonymous abandonment was not gender-neutral, but reflected a clear son preference: sons were considered as assets, girls as liabilities. We find that the ruota’s closures contributed to the reduction of sex selectivity in abandonment, an historical driver of the phenomenon of “missing girls”.

So why did abandonment fall so sharply? The answer reveals an uncomfortable truth. While the ruota was a tool of social control for unwed mothers, it served another purpose entirely for married couples: it was a publicly funded means of limiting family size. The evidence shows that the ruota was not simply a last resort for desperate women, but a deliberate instrument of family planning. When the wheel was removed, families adapted. Births declined by approximately 4%, and this decline was primarily due to married couples making different choices about family size.

This forgotten lesson from 19th-century Italy speaks directly to modern debates. A policy of anonymous abandonment, intended as a compassionate safety net, also functioned as a tool of social control while simultaneously creating a larger social problem by encouraging abandonment. As modern societies consider reinstalling these same devices, they must reckon with the historical evidence: closing the wheels did not leave vulnerable children worse off. Instead, it prompted a shift toward active family planning, reduced abandonment, and ultimately saved lives.

To contact the authors:

Marco Molteni

University of Turin

Giuliana Freschi

giuliana.freschi@santannapisa.it

Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa