EHS 2018 special: Wine prices in Anglo-Gascon trade, c.1337-c.1460

Robert Blackmore (University of Southampton)

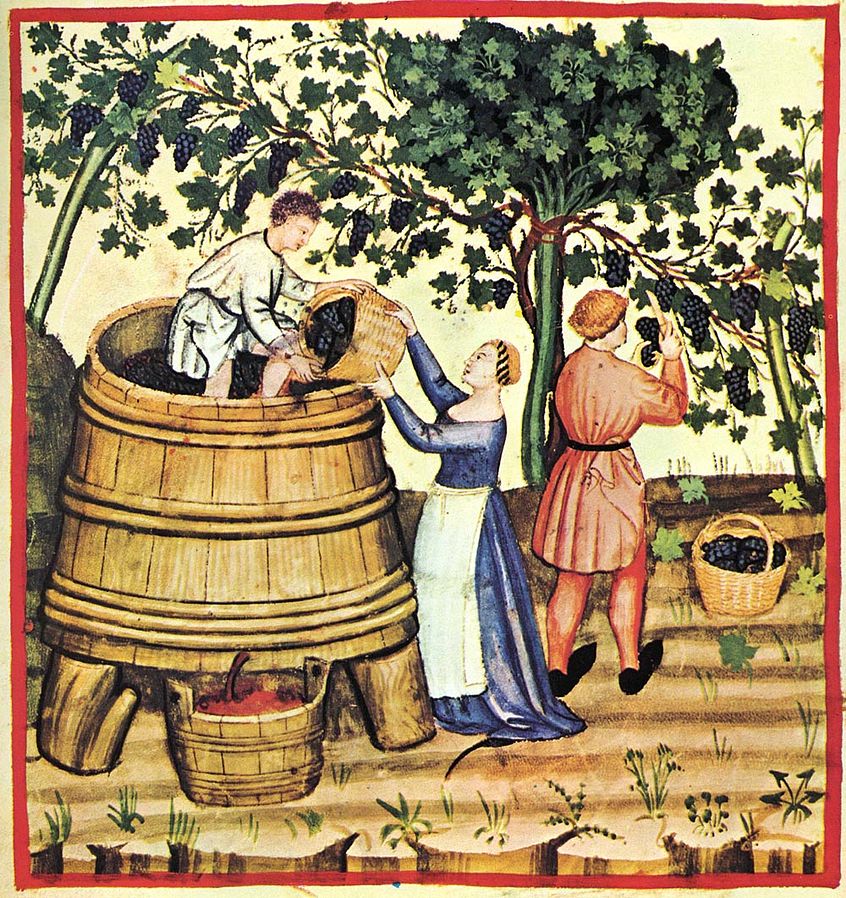

9-autunno,Taccuino Sanitatis, Casanatense 4182. Available at <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:29-autunno,Taccuino_Sanitatis,_Casanatense_4182..jpg>

Episodes of major market volatility are rarely out of the headlines today. Their ramifications, though considerable, are discussed as if these were somehow new, and that they are the result of how economies are structured in our globalised world. Yet prices in international markets in the late middle ages could be just as volatile and have just as far-reaching consequences.

The wine trade between Gascony and England is one key example. Gascony, in modern southwestern France, was part of the medieval duchy of Aquitaine: a territory ruled by the English crown almost without interruption from 1154 to 1453.

Geography and geology permitted the production of just one commodity, wine, and as a result the region was dependent, like so many modern states specialised in fossil fuels or mining, on export earnings to pay for the purchase and import of food and all other goods from distant markets.

My research provides a better understanding of the possible factors that influenced fluctuations in prices, and their knock-on effects. To achieve this, I use wholesale prices in Bordeaux and Libourne from between 1337 and 1466, largely sourced from surviving original documents stored both in the Archives départementales de la Gironde in Bordeaux and the National Archives in London.

As today, extreme climactic events, as well as disruption by war, or demographic catastrophes such as disease or famines, can be understood to cause sudden shifts in supply. Likewise there were abrupt changes in local demand, for example, in 1356 the arrival of a victorious Edward, the Black Prince, with his army laden with ransoms and plunder after the battle of Poitiers, can be observed in the data.

Volatility was exacerbated by government intervention: particularly a 1353 English law that had constrained certain merchants from buying up stock in advance at pre-agreed prices, as would be done in modern markets. Likewise, ill-considered price controls at retail in England probably caused suppressed trade.

Critically, wine was a luxury in northern European ale-drinking societies, where only the rich would tolerate high prices, so any brief disruptions in supply or local demand disproportionately affected the level of exports.

Such characteristics also meant that wine prices were responsive to wider economic shocks in ways that would be well understood today. Monetary policy mattered. England and Gascony used different currencies with a changing exchange rate. As the Gascon livre appreciated against sterling in the two decades after the Black Death (1348-9), prices rose for foreign buyers, then later devaluations, such as in c.1370, 1413-4 and c.1440, made purchases suddenly cheaper, and triggered noticeable increases in English wine imports.

Yet, for Gascony, as in Venezuela today, an over-dependence on foreign imports meant such surges or falls in the value of one single exported commodity resulted in sudden strong trade surpluses or deficits. Foreign currency, then in the form of precious metals, poured in and out of the economy with fluctuations in the wine trade.

This made prices, and by extension, the duchy of Aquitaine’s whole economy, even more unstable. In the end inflation set in as production declined and later years of English Gascony were mired in an economic depression that contributed to the region’s loss to the French crown in 1453 at the end of the Hundred Years’ War.