Women in finance in modern Britain

In this post James Taylor of Lancaster University discusses their new book, supported by an EHS Carnevali Small Research Grant.

—

Historical work on women and finance has proliferated since the early 2000s. This research has explored women’s early and extensive involvement as investors in the national debt and in joint-stock ventures from the late seventeenth century. Despite restrictions such as the law of coverture, historians have found that women could and did invest their money with a great deal of freedom. However, this work implicitly or sometimes explicitly assumes that women were not acting as financial intermediaries on behalf others – for example as stockbrokers – until more recent times. Indeed, it was not until 1973 that women were finally allowed to become members of the London Stock Exchange.

But when researching the history of popular investment in the late nineteenth century – generously funded by an Economic History Society Carnevali Small Research Grant – I began to discover references to women working as stockbrokers. In time, I found more examples, and this piqued my curiosity. Who were these women, and why did they want to work in finance? What kind of businesses did they run, and were they successful? And how did the stock exchanges respond to this challenge? I switched the focus of my research from the broader investment picture to the more specific question of women working in finance. What I initially imagined would be an article eventually became a book, published by Oxford University Press in 2025.

My Carnevali Research Grant allowed me to visit the archives I needed in order to build a full picture of the financial environment women faced. In particular, I wanted to explore the attitudes of stock exchanges to women, and to find out what happened when women began applying for membership. In London I was able to view the records of the London Stock Exchange at Guildhall Library – though these terminate in the 1950s. Just as importantly, however, I accessed the surviving records of other stock exchanges, such as Birmingham, Leeds, and Sheffield.

To some extent, the minute books painted a picture of confusion. Clearly, women were not supposed to apply, and there were no precedents to explain to men how to deal with the situation. The records also revealed a steely determination to keep the stock exchanges male-only.

Yet stock exchanges never had a monopoly. True, when markets first became institutionalised, this gave men the opportunity to freeze out the kinds of women whom historians such as Amy Froide and Ann Carlos and Larry Neal have shown operated as intermediaries in the coffee shops of Exchange Alley in the early eighteenth century. But there were always those brokers who chose to – or had to – operate outside. And from the 1880s, this outside market began to boom. Rising standards of living meant more people had money to invest. Married women in particular were gaining newfound rights over their money with the Married Women’s Property Acts. There were new investment opportunities at home and abroad, publicised by a specialist financial press. A new wave of ‘outside brokers’ emerged to cater to small investors wanting to go into the stock market but not knowing how. And among these outside brokers were small numbers of women.

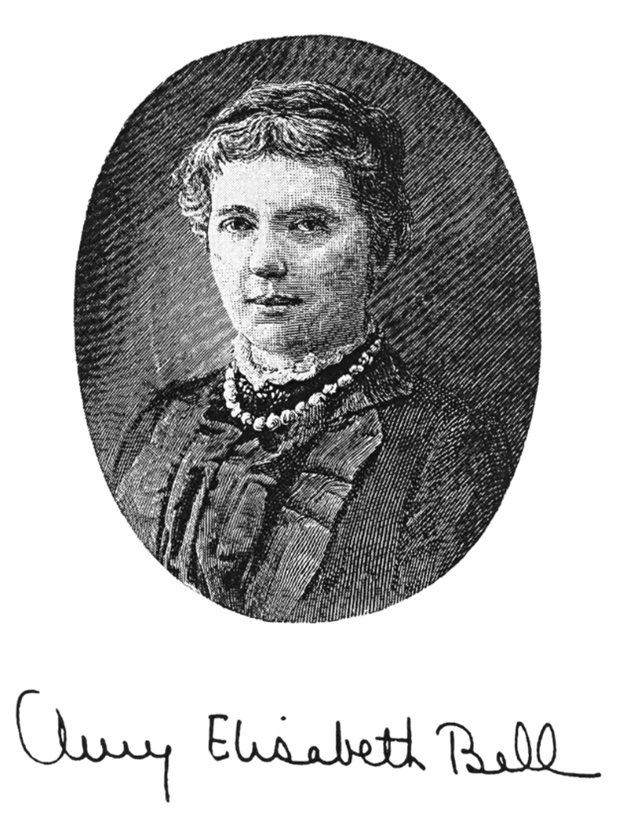

The earliest of these, women like Amy Bell, could not train as stockbrokers’ clerks, as no stockbrokers hired women as clerks, so they had to pick up what skills they could and launch their own ventures. Bell succeeded, largely by catering to female investors who did not want to trust their finances to a male family member. Her services were as much educational as financial. ‘I want to make women understand their money matters and take a pleasure in dealing with them’, she told a reporter.

Though Bell was happy to carve out a gendered niche in the stockbroking world, those who came after her tended to trade differently. Beatrice Gordon Holmes, for example, established a series of investment trusts with her male partner which catered to female and male investors alike. She usually downplayed the importance of gender in business, writing ‘if I am asked what women, as women, can contribute to finance, my candid reply would be “Nothing.” There is no sex in discounting a bill or in judging a balance sheet.’ At the same time, Holmes was keen to encourage other women into business, and in 1938 helped to establish the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs in Britain, becoming its first president.

My book ends with women’s eventual admission to the London Stock Exchange in 1973. Though this was celebrated like a victory – and was a massive achievement after the resistance from men they had faced – it failed to change the gendered culture of finance. As recently as 2024, a Treasury Committee on ‘Sexism in the City’ found damning evidence of continuing ‘misogyny, sexual harassment and bullying’.

The examples of women like Bell and Holmes suggest that, if we choose to look outside the official exchanges, a more diverse financial environment comes into view: an environment where women could find clients and trade successfully and profitably. Acknowledging the efforts of those women who challenged established beliefs and defied men’s monopoly on high finance by forging their own careers might represent an important step towards imagining a different kind of market.

References:

Carlos, Ann M. and Larry Neal, ‘Women Investors in Early Capital Markets, 1720–1725’, Financial History Review 11, no. 2 (2004): 197–224

Erickson, Amy Louise, ‘Coverture and Capitalism’, History Workshop Journal 59, no. 1 (2005): 1–16

Froide, Amy M., Silent Partners: Women as Public Investors during Britain’s Financial Revolution, 1690–1750 (Oxford, 2017)

Holmes, Miss Gordon, In Love with Life: A Pioneer Career Woman’s Story (London, 1944)

House of Commons Treasury Committee, Sexism in the City, Sixth Report of Session 2023–24, HC 240, 5 March 2024

Taylor, James, ‘Inside and Outside the London Stock Exchange: Stockbrokers and Speculation in Late Victorian Britain’, Enterprise and Society 22, no. 3 (2021): 842–77

To contact the author:

Professor James Taylor

School of Global Affairs, Lancaster University