A Millennium of (Un)Change: Lending Interest Rates and Money Supply in China, 618 – 1911

In this blog post, Yangyang Liu of the London School of Economics introduces their research which was supported by a grant from the EHS Research Fund for Graduate Students.

—

Key words: Banking, Money, Interest, Capitalism, China

Finance, particularly banking, has been overlooked when explaining the Great Divergence between the West and the East until recently. The significant role that banks have played in the past six hundred years has drawn a lot of attention from financial historians in the fruitful international literature. However, a crucial area remains a largely unexplored: the historical origins and evolutions of China’s banking. China, having experienced many economic ups and downs in her continuous 5000-year history, had only established her first modern bank on the eve of the 20th Century. So why did banks develop so late in China?

Theory and Hypothesis:

The change in interest rates is the driving factor behind any changes in demand for loans. In the Theory of Loanable Funds and the Liquidity Preference Theory, it is suggested that an increase in money supply results in a decrease in interest rates. According to this theory, increased money supply reduces the compensation cost, thus lowering interest rates. My hypothesis is that the persistent high lending interest rates inhibited borrower’s willingness to borrow. The exceptional high cost of capital disincentivized borrowing and in turn China missed the opportunities to support large infrastructure investments, failing to catch-up to western industrialization. As a result, China was and unable to become a capitalist society.

Primary Archival Sources:

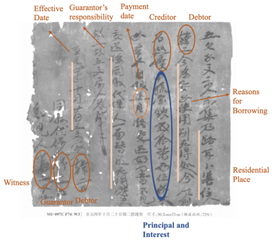

To rigorously investigate my hypothesis on the role of lending rates, I compiled a unique dataset through extensive archival research conducted in China and the UK. This dataset, spanning more than a millennium from 618 to 1911, includes detailed loan transactions with information on creditors and debtors, their socioeconomic status, interest rates, repayment terms, and collateral types. The dataset currently encompasses approximately 15,000 transactions and over 100,000 entries, constituting one of the most comprehensive historical databases on Chinese lending practices assembled to date. The archival sources include materials from both China and the UK. In China, I accessed the First Historical Archives of China (memorials to the emperor, 1644-1918), and the Shanghai Municipal Archives (financial statements of Chinese and foreign banks from 1880 onward). In the UK, I accessed the British Library (temple loan contracts since the Tang dynasty), the National Archives (records on silver accounts and banking agreements), and the British Museum (Chinese coin mintage records spanning 618 to 1911).

Results:

Conclusion:

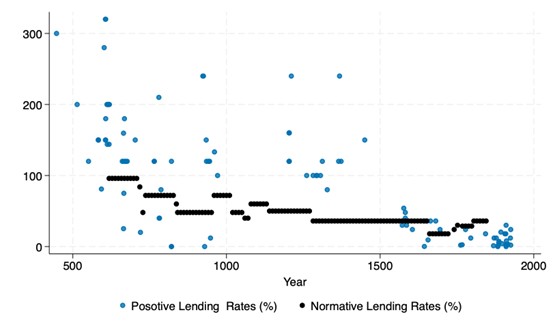

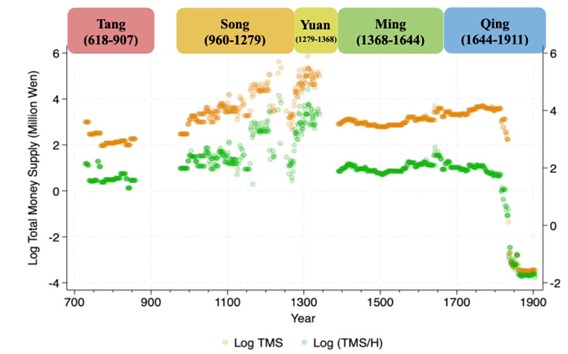

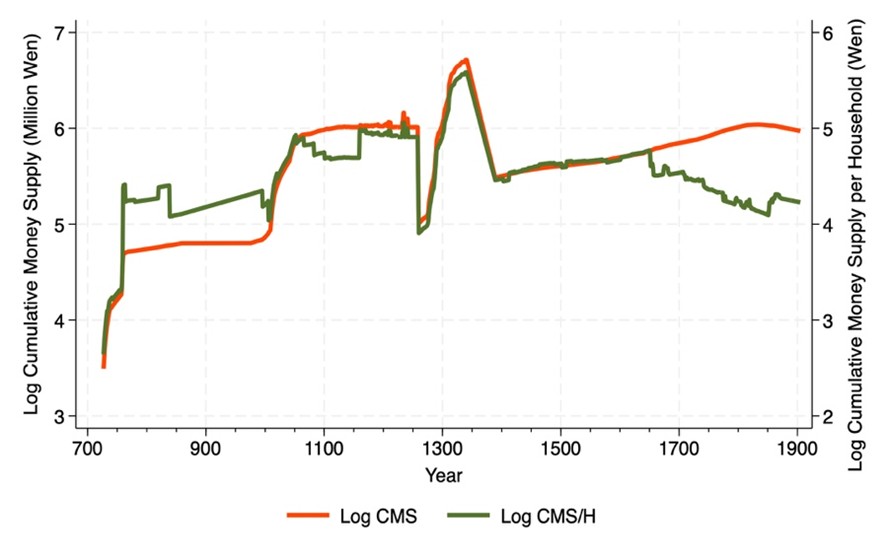

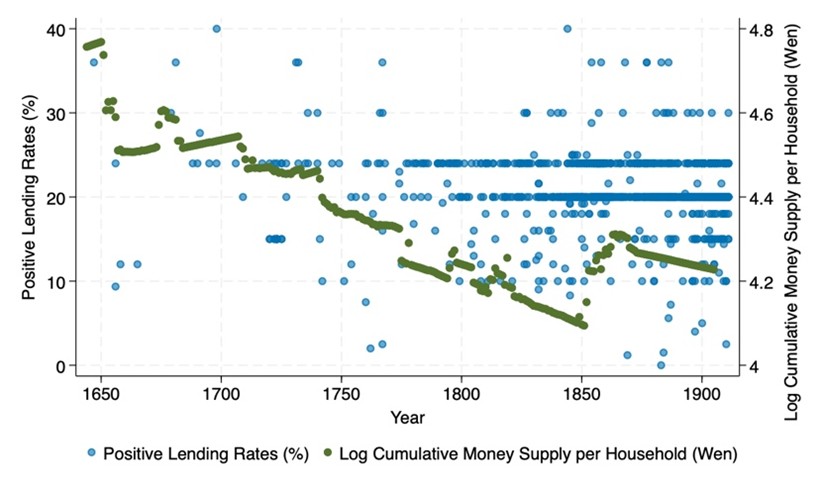

Normative lending interest rates are the ceiling rates set by the government with the aim to avoid usury lending. The Twenty-Four Histories record detailed rules and regulations in each dynasty, including the lending rate benchmark, and thus are the main source for normative lending rates. Positive lending rates are the rates agreed in real transactions. Therefore, loan contracts are my primary source as they record the actual details of common people’s daily transactions. My results show the changes in lending interest rates over one thousand years. The official/normative interest rates cap stabled at 36% to 48%. However, real/positive lending interest rates in practice experienced a dramatic change, peaking at 200% to 300% and staying at 70% to 100% for a very long period, around seven hundred years. They then gradually decreased from 50% in the 15th century to 20% in the 20th century. The persistent high lending interest rates impeded borrowing activities, which in turn made banking less profitable and thus delayed the development of banks. The relationship between lending interest rates and the money supply is positively correlated, which contradicts classical loanable theory.

Historical evidence in this research shows that an increase in the money supply at the national level tends to raise positive lending rates. However, during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), I observed that both lending rates and the money supply at the household level decreased, and modern banks emerged.

Bibliography:

Abbott, P.U. (1934) ‘The Origins of Banking: The Primitive Bank of Deposit, 1200-1600’, The Economic History Review, 4(4), pp. 399–428.

Goetzmann, W.N. (2017) Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Lin, J.Y. (2012) The Quest for Prosperity: How Developing Economies Can Take Off. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McAndrews, J. and Roberds, W. (1999) Payment Intermediation and the Origins of Banking. FRB of New York Staff Report No. 85. New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Needham, J. (1969) The Grand Titration: Science and Society in East and West. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Pomeranz, K. (2000) The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rosenthal, J.-L. and Wong, R.B. (2011) Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

To contact the author:

Yangyang Liu

London School of Economics